It’s a misconception in small Maine towns that homelessness is not an issue.

Visitors to Midcoast Maine assume that if they don’t see people living in tents on the sidewalk or green spaces in coastal and inland towns, Maine doesn’t have the same housing problems as urban areas.

What they can’t see are the campers and RVs that stay hidden in the backroads and rural areas of Maine, where dozens of families have been forced out of permanent housing.

Several Midcoast social service agencies have been searching out these families this winter. Emily Caroll, a case manager, for Kennebec Behavioral Health, and Jess Breithaupt, Food Security Community Connector at Healthy Lincoln County, have a two-part aim to go above and beyond to reach them.

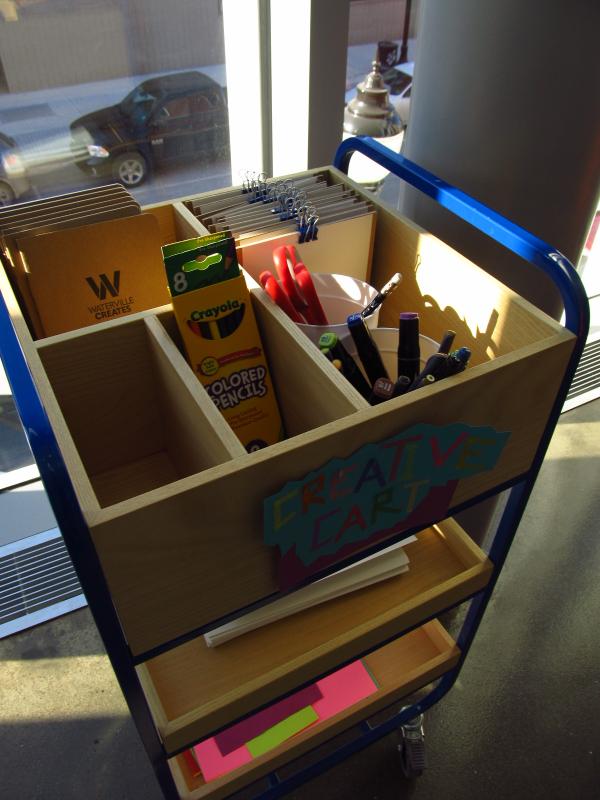

Caroll, Breithaupt, and volunteers who help source and assemble food and supplies, have been driving a van filled with food, water, medicine, blankets, pillow, coats, clothing, cleaning items, toiletries, and other comforts, to families who are living deep in the woods in campers and RVs, mostly off-grid.

“We at Healthy Lincoln County have been working with a variety of volunteers, churches, and organizations, collecting supplies to be able to do this level of outreach,” said Breithaupt. “We’ve also been able to distribute NARCAN to prevent overdoses and to make sure they have medication if they need it.”

The effort started out of practical reasons: to record a “point-in-time census” and survey how many people across the state are experiencing homelessness for at least one night, according to Breithaupt. “Getting this accurate information will help us bring in more money to each county to build programs,” she said.

“Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve visited 21 families in locations where people are living in campers,” said Breithaupt. “It blows my mind. I didn’t know it was that many people. And that’s just one county.”

None of these families are on a register, none of them expect anyone in a van to just drive up to their campers. The project is relying on anonymous tips from neighbors and community members in order to even find these families.

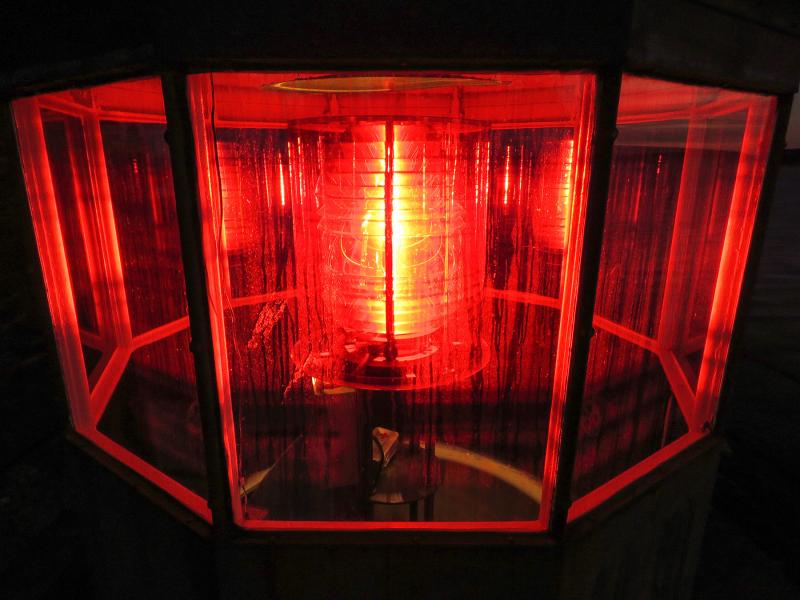

A day after two back-to-back snowstorms in late January, Caroll and Breithaupt drove their brightly-colored van down a rutted dirt road, searching on both sides for a tell-tale camper with tarps over it. The tarps, along with footprints in the snow, are a giveaway that a family might be living there.

Getting out of the van in their heavy coats and snowboots, Breithaupt and Caroll trudged down an unplowed part of the road and called out, “Hello—”

If the residents of the camper were initially wary to see strangers, their fears usually dissipated once they saw the colorful van and heard why Breithaupt and Caroll were there.

“We tell them that we’re here to drop off any supplies and to feel free to come to the van and take anything they need,” said Breithaupt. “From that point, if the person is willing, we ask him or her for a little bit of data for the census.”

Families are initially shocked, then amazed, then thankful, that someone cares that much to come to find them and to offer help.

“These are proud Mainers,” said Breithaupt, explaining why people in their circumstances don’t seek out help on their own.

To get a sense of the demographics of these camper communities, Breithaupt and Caroll reported that in their missions, they’ve come across families with children, single mothers with children, and communities of adults.

Often, once the people begin talking, Breithaupt says, she starts to hear the whole story.

“One family was evicted from their apartment while they had COVID-19 virus,” said Breithaupt. “It would have been an issue they could have taken to court, but they didn’t have the resources to do that, so they moved onto a small plot of land and put a camper on it and that’s the situation they’re trying to get out of now.”

Many of the families Carol spoke to are looking for housing, but there is nothing available to buy and the skyrocketing rents in Maine have been too prohibitive to afford.

“They’re stuck. Vouchers have run out, and hotels that previously housed some of my clients have closed,” said Caroll.

Breithaupt said while the housing market has been tight for more than a decade, the massive influx of newcomers to Maine as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic put a further strain on housing and rental resources.

“You can put two and two together,” she said. “A rent that was $800 per month pre-pandemic is now $1,600 a month. How can anyone afford that?”

“The other problem that wasn’t necessarily COVID-19-related was the rise of Airbnb properties,” said Caroll. “There were a lot of smaller, lower-income rental properties we saw turn into Airbnbs over the summer. They figured they could get more money renting the unit for three months and close it up the rest of the year. It took away a lot of housing for low-income families.”

The van of supplies is providing a much-needed resource to these families during the winter.

“One family we just visited experienced the joy of being able to pick out what they wanted, such as toothpaste,” said Caroll. “They were excited to have blankets and food. When we’re there, we’re also giving them information on how to access more help through Healthy Lincoln County. One elderly disabled gentleman had no idea that we could have meals delivered to him. The look of relief on his face when we told him there was a meal delivery service available and if he couldn’t get out to the soup kitchen, we’d bring it to him—that moment really stuck with me. ”

Through casual observation, Caroll and Breithaupt have noted that some of these families are living without heat, or if they have heat, it’s jury-rigged, sometimes dangerously, from temporary tanks into the camper.

“There are a lot of tarps strewn over the tops of the campers to keep out the snow and often, people use whatever insulating material they can find to stuff up under and around the camper,” said Breithaupt.

Breithaupt said that the solutions to finding housing for low-income earners are still not on the horizon, although it’s been at the forefront of every social service agency’s agenda.

“There are tiny-housing communities that are on the horizon in some parts of Maine,” she said. “I’ve gone to Rotary meetings and asked members if they have in-law apartments they’re not using that could be re-purposed as short-term housing.”

For now, it’s just Mainers making do, as they’ve done for centuries, surviving, getting by.

For more information or how to help visit: healthylincolncounty.org

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com