Revisiting David Ackles

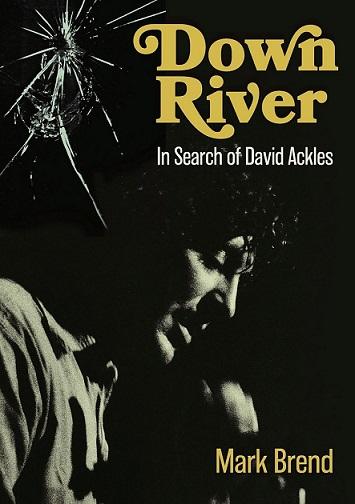

Down River: In Search of David Ackles by Mark Brend (Jawbone Press, London, 248 pages). If you are familiar with the name David Ackles, you probably really liked his music, although he may be unknown to the younger members of my audience, as the last of his four albums was released in 1972 and Ackles died in 1999.

Ackles best album, “American Gothic,” was his third for Elektra Records, released in July 1972, only six months after I started reviewing albums. It proved one of my favorites of the year, as I especially enjoyed its theatrical leanings. The album made such an impression on me that one of its songs, “Love’s Enough,” was performed by a friend during my wedding, along with Paul McCartney’s “Maybe I’m Amazed.”

In my review of “American Gothic,” I wrote that Ackles' music blends rock, pop and theatrical elements seamlessly, and his lyrics explore deep emotional themes and storytelling.

Although a brilliant musician, Ackles, who was born in Rock Island, IL on Feb. 20, 1937, was never really comfortable performing his songs live on stage, even though he had experience in performing musical theater and appeared as a child actor in the eight films of the “Rusty” series, produced for young audiences between 1945 and 1949 by Columbia Pictures. Rusty was a German Shepherd dog and Ackles played Tuck, the friend of Danny Mitchell in the B-movies.

Ackles first two Elektra albums were “David Ackles” (September 1968) and “Subway to the Country” (January 1970). Both received critical praise but failed to find an audience, as Ackles really was not part of the singer-songwriter names that had been drawn to Elektra Records at that time, artists such as Judy Collins, Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton.

In 1972, Ackles’s third album, “American Gothic,” was released to a flurry of praise from U.K. and U.S. press reviewers. It was even declared to be “the ‘Sgt. Pepper’ of folk” and one of the greatest records ever made. Still, the album, recorded in a home studio in England and produced by Elton John lyricist Bernie Taupin, failed to sell, just like its two predecessors. With changes at Elektra, Ackles was dropped from the label. He made one more album, “Five & Dime” (October 1973) for Columbia Records, but when his supporter, Clive Davis was removed from Columbia for a time, the record received no publicity push, other than sending copies to reviewers.

From then on, Ackles simply vanished. He found work, raised a family and died 26 years later, having never made another record. Much of his final years were spent working on two potential musicals.

Today, Ackles’ music is largely consigned to the streaming netherworld. Author Brend points out that it has not been properly repackaged, and thus Ackles remains largely unknown. Yet his admirers range from Black Flag’s Greg Ginn to indie polymath Jim O’Rourke to Genesis drummer turned platinum-selling solo artist Phil Collins. In 2003, when Elvis Costello interviewed Elton John for the first episode of his “Spectacle” television show, the two spoke at length about Ackles’ great talent, before performing a duet of his song, “Down River.”

John had been a fan of Ackles’ music and was thrilled to be on the same bill with Ackles when he played the Troubadour club in Los Angeles in August 1970. According to Brend, John originally was slated to open for Ackles, but Ackles requested the flip. Those Troubadour shows helped launch John as a star in the United States. John dedicated his 1970 album “Tumbleweed Connection” to Ackles with the line, "to David with love."

In this comprehensive volume, Brend draws on conversations with Ackles himself, members of his family, collaborators including Taupin, and archive material. The book positions Ackles as one of the great maverick talents of popular music -- an equal of the better-known Scott Walker and Tom Waits – and seeks to understand the commercial failures despite his obvious gifts, which leads to a discussion of the fickleness of fame and cult status. Brend wonders whether Ackles’ music is just too strange with its combination of different roots and styles. Finally, he draws on what the answers to those questions has to say about the mythmaking of the popular music industry.

Brend is a writer and musician. His first published music journalism was a Mojo “Buried Treasure” feature about Ackles’ first album, and the first chapter of his first book, “American Troubadours: Groundbreaking Singer Songwriters of the ‘60s” (Backbeat, 2001), was about Ackles. He has written several other books about music, including “The Sound of Tomorrow: How Electronic Music Was Smuggled into the Mainstream” (Bloomsbury, 2012) and “Strange Sounds: Offbeat Instruments and Sonic Experiments in Pop” (Backbeat, 2005). Grade: book A

About this blog:

My music review column, Playback, first ran in February 1972 in The Herald newspapers of Paddock Publications in Arlington Heights, IL. It moved to The Camden Herald in 1977 and to The Courier Gazette in 1978, where it was joined by my home video reviews in 1993. The columns ran on VillageSoup for awhile, but now have this new home. I worked at the Courier Gazette for 29 years, half that time as Sports Editor. Recently, I was a selectman in Owls Head for nine years.