The Jellyfish in the Room

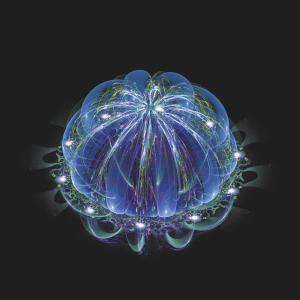

A Lions Mane jellyfish, Aug. 24, on the shore of Penobscot Bay. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A Lions Mane jellyfish, Aug. 24, on the shore of Penobscot Bay. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Richard Podolsky came to Maine to work on the National Audubon Society project that restored Atlantic puffins to Maine Islands. He went on to earn a doctorate in marine ornithology at the University of Michigan and to teach oceanography there and at the University of Hawaii. Richard did postdoctoral research in the Galápagos Islands before returning to Maine where he was the first director of science and research at the Island Institute. Richard lives and Camden and leads natural history excursions on the Schooner Surprise every summer.

Richard Podolsky came to Maine to work on the National Audubon Society project that restored Atlantic puffins to Maine Islands. He went on to earn a doctorate in marine ornithology at the University of Michigan and to teach oceanography there and at the University of Hawaii. Richard did postdoctoral research in the Galápagos Islands before returning to Maine where he was the first director of science and research at the Island Institute. Richard lives and Camden and leads natural history excursions on the Schooner Surprise every summer.

A Lions Mane jellyfish, Aug. 24, on the shore of Penobscot Bay. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A Lions Mane jellyfish, Aug. 24, on the shore of Penobscot Bay. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Richard Podolsky came to Maine to work on the National Audubon Society project that restored Atlantic puffins to Maine Islands. He went on to earn a doctorate in marine ornithology at the University of Michigan and to teach oceanography there and at the University of Hawaii. Richard did postdoctoral research in the Galápagos Islands before returning to Maine where he was the first director of science and research at the Island Institute. Richard lives and Camden and leads natural history excursions on the Schooner Surprise every summer.

Richard Podolsky came to Maine to work on the National Audubon Society project that restored Atlantic puffins to Maine Islands. He went on to earn a doctorate in marine ornithology at the University of Michigan and to teach oceanography there and at the University of Hawaii. Richard did postdoctoral research in the Galápagos Islands before returning to Maine where he was the first director of science and research at the Island Institute. Richard lives and Camden and leads natural history excursions on the Schooner Surprise every summer.

This year, the Gulf of Maine delivered one of its most surprising seasons in living memory—not just for scientists, but for everyone who lives, works, or plays along its coast. An extraordinary bloom of Arctic jellyfish arrived, the product of dramatic changes far to the north and unusual local weather. What happened here in 2025 isn’t just a quirky anecdote: it’s a window into a rapidly evolving climate system and a warning about the 'new normal' that could become commonplace in coming years.

The Gulf of Maine is no stranger to surprises. But this year, even seasoned observers found themselves doing a double-take on the local waters—as if the ocean had decided to offer up a riddle, and the jellyfish were the punchline. Only it isn’t very funny. If you’ve spent time along our coast this spring and summer, if you fish, sail, swim, or simply walk the wrack line at low tide, odds are you were nudged to attention by the lion’s mane jellyfish—sometimes as wide as a truck tire—bobbing just beneath the surface or washed onto the sand like some ancient, rubbery oracle.

Hang around any wharf from Port Clyde to Eastport and you could overhear the stories: “Never seen them this thick.” “Swallowed a mooring line whole, almost!” “We had to turn the engine off, just for fear of clogging the intake filter.” It didn’t take scientific instruments to know the Gulf was having an out-of-the-ordinary spring.

But what happened? Most folks, rightly, look at these blooms as a nuisance or a curiosity—bad news for swimmers, maybe, or a worry for lobsterfolk running lines through mats of stinging tentacles. Yet the real story begins far beyond our horizon, up in the polar twilight, with a patch of water that didn’t freeze.

The Big Pulse from the High North

This past winter, something happened that’s never happened before—a patch of Arctic Ocean, “about the size of California,” simply failed to develop the usual winter sea ice. That isn’t a metaphor; it’s a hard, measured fact. For scientists, it set off ringing alarms. For the ocean, it set off a chain reaction, every piece connected to every other, like stones skipping across a pond. That patch of open water absorbed weeks of uninterrupted sunlight when it should have been reflecting solar energy out to space. Picture billions of kilojoules pouring into the Labrador Current, nudging it a tick warmer than usual, priming a bloom of jellyfish, plankton, and all their creatures in tow.

When spring came to the Gulf of Maine, we got more than the usual trickle of Labrador water—we got a rush. Jellyfish crowded in, not so much born here as delivered, like a shipment gone sideways, driven by river-sized currents from a supercharged Arctic. The Gulf, always a crossroads—where Arctic and subtropical waters meet, where islands and mainland chafe together—became the landing spot for a planetary experiment.

Clouds, the Hidden Actors

But the Gulf has tricks of its own. Anyone watching the sky this May, June, and July can tell you: we had cloud, and we had plenty of it. Thirteen weekends in a row of greyscale weather, fog like cotton batting, rain that pattered steady on docks and windows. From a satellite’s eye, the sunlight that did reach our surface was sharply muted, like a dimmer switch left halfway. Research shows that persistent cloud anomalies can swing Gulf of Maine surface temperatures by more than 0.5°C. If the Arctic was having a record-setting solar feast, we were fasting by comparison.

This “yin and yang” of climate may sound poetic, but the science is rock solid: put a gulf’s worth of clouds between the sun and the sea, and you built the year’s most important defense. Yes, by mid-July the sun broke through long enough to spike the sea-surface temperatures—our own “hot jellyfish parade”—but those surges were short-lived, and the Gulf cooled right back down, almost as quickly as it had warmed.

What the Jellyfish Know That We Don’t

If the lion’s mane is a harbinger—and it is—they arrive because the system has already changed up north, and because our local conditions allowed them entry, for a time. Recent research confirms that lion’s mane jellyfish are cold-water specialists whose Arctic habitat may expand dramatically as climate warms. But the whipsaw is sharp: just as suddenly as they appeared, the jellyfish vanished, their numbers dropping off in only ten days. The food was gone, or the water cooled, or both. If you’re a puffin or a tern, this kind of seesaw matters—a lot. We dodged disaster this year, but it wouldn’t have taken much—a few more clear days in June, a sticky block of high pressure in mid-July—and our Gulf would have leapfrogged 2012 and 2023 for the number of record-hot days, and the birds, the herring, the lobster, and the people who depend on them would have been in for a grim, hungry ride.

Ask those who worked the bay in 2010, 2012, 2023—years of relentless sun, stable high pressure, and sky-high sea temperatures. These years had 19, 24, and 20 days, respectively, in July, ranking among the top five warmest July days ever recorded for their calendar dates—far exceeding this year’s five such days. Seabird chicks starved as their parents dove for prey forced deep or absent altogether; lobster and shrimp shifted, crab and clam dynamics upended. But those years did not see jellyfish blooms like 2025. This year, the gorilla in the room—our stinging visitors—weren’t just a quirk of weather. They were the herald of a much bigger change, proof that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic anymore.

What Does This Mean for Us?

Here’s the hard part. We like to think of the Gulf of Maine—and by extension, our own slice of the world—as stable, or at least reliable in its patterns. Yet the Gulf of Maine is warming nearly three times faster than the global ocean average, and projections suggest Arctic sea ice will continue its steep decline. We track the temperature, the fog, the birds, the fish. When the numbers jump, or the patterns break, it’s tempting to see it as a one-off, a fluke, a freak of weather. This year, we can thank our cloud cover and the timing of ocean currents for pulling us back from the brink—those “offsets” that keep the system homeostatic, for now. But don’t confuse luck for resilience.

Jellyfish are not just a summer nuisance or a dinner for a passing Mola mola. They are the bellwethers of a changed ocean, responding almost instantly to shifts in currents, nutrients, and temperature. When they arrive en masse from the north, they signal that the old firewalls—the buffers between the Arctic and the Gulf—are failing.

Here’s the hope: the Gulf of Maine, with its islands, estuaries, and industrious communities, has always been a place that sustains, that bounces back. But as the pace of change accelerates, those “offsets” may become fewer, and the swings more extreme. Eventually, we may well have a season without the helpful accidents of clouds and currents to soften the hammer blow of a record-hot Arctic.

The Edge of the Tipping Point

Here’s what we need to face directly: someday soon—perhaps next summer, or the one after—the offsets will fail. The Arctic will send another pulse of heat, biology, or chaos down the pipeline. But next time, the clouds may not come to save us. The currents may stack warm layers instead of flushing them. And when that happens, the systems we now assume to be resilient—lobster, herring, sand lance, the migrating seabirds—may not just wobble. They may crash.

Imagine a July where the Gulf of Maine crosses 68°F and stays there. Prey fish dive deeper. Lobster molting shifts weeks off rhythm. Tern colonies abandon chicks. Eiders lose broods as their food vanishes. Puffins return endlessly with nothing in their beaks. Offshore, warm-core eddies trap nutrients in the wrong place. Onshore, jellyfish strand in mats, fouling beaches with stinging decay.

This isn’t science fiction—it’s scientific extrapolation. The years of 2010, 2012, and 2023 showed us what atmospheric forcing can do by itself. 2025 added the Arctic plot twist. With fewer safety valves the outcome becomes not just probable, but inevitable.

That’s why the jellyfish in the room matters. They weren’t an anomaly. They were a warning, delivered with tentacles. They showed us that the Arctic is no longer a distant player. It’s here. The firewall has gaps. How we respond the next time—and there will be a next time—will define not only how well we protect this place we love, but whether we’re ready to adapt to a future that’s already knocking.

Richard Podolsky is a marine ornithologist who lives in Camden, Maine. You can find Richard all summer long leading natural history tours on Penobscot Bay out of Camden on Schooner Surprise. For a live, in-person version of this essay signup for one of these tours. This essay was inspired by observations made during these and other sojourns.

References