The mysterious speakeasies of Rockland, where history whispers old secrets

The secret door to the speakeasy on 435 Main Street, Rockland, Maine. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The secret door to the speakeasy on 435 Main Street, Rockland, Maine. (Photo by Kay Stephens) The stairway up to the attic of 435 Main St. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The stairway up to the attic of 435 Main St. (Photo by Kay Stephens) The door with the “knock knock” panel. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The door with the “knock knock” panel. (Photo by Kay Stephens) “An approved formula especially indicated in run down and weakened conditions.” (Photo by Kay Stephens)

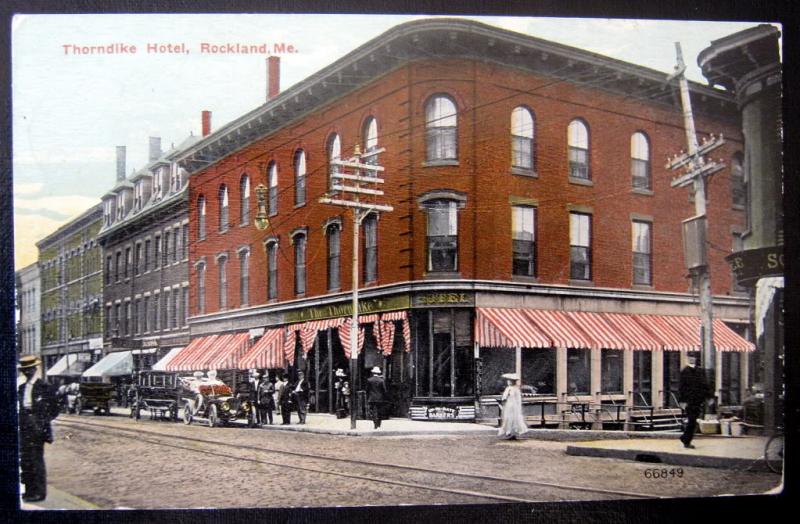

“An approved formula especially indicated in run down and weakened conditions.” (Photo by Kay Stephens) The front of the Thorndike Hotel. Around the back is the basement entrance to what was reputedly another speakeasy. (Courtesy Rockland Historical Society)

The front of the Thorndike Hotel. Around the back is the basement entrance to what was reputedly another speakeasy. (Courtesy Rockland Historical Society) The secret door to the speakeasy on 435 Main Street, Rockland, Maine. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The secret door to the speakeasy on 435 Main Street, Rockland, Maine. (Photo by Kay Stephens) The stairway up to the attic of 435 Main St. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The stairway up to the attic of 435 Main St. (Photo by Kay Stephens) The door with the “knock knock” panel. (Photo by Kay Stephens)

The door with the “knock knock” panel. (Photo by Kay Stephens) “An approved formula especially indicated in run down and weakened conditions.” (Photo by Kay Stephens)

“An approved formula especially indicated in run down and weakened conditions.” (Photo by Kay Stephens) The front of the Thorndike Hotel. Around the back is the basement entrance to what was reputedly another speakeasy. (Courtesy Rockland Historical Society)

The front of the Thorndike Hotel. Around the back is the basement entrance to what was reputedly another speakeasy. (Courtesy Rockland Historical Society)ROCKLAND — 435 Main Street, the four-story brick building in the heart of downtown Rockland, is being renovated into a multi-use market this summer called Main Street Markets. But that’s not the only fascinating element of this building. It once hosted a mysterious speakeasy on its top floor.

Developer Rick Rockwell has grand plans for the building, aiming to salvage every beam, every brick and every architectural element he can as he works to get the building ready for tenants on the top floor and and a market and retail space on the bottom floors. Rockwell, who grew up in Port Clyde, will offer a consignment space for locally produced food, beer and wine. The cafe will offer salads, juices, shakes and smoothies while other sections of the market will be a one-stop shop for locally harvested seafood, produce and meats. He even has plans for a beer and wine section with a brew pub in the works.

Rockwell was gracious enough to show me the speakeasy that once occupied the attic space of the building back in the early 1900s, during the roaring times of Prohibition.

In 1851, Maine became the first state to ban the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, only allowing an exception for "medicinal, mechanical and manufacturing purposes." Other states followed Maine’s lead and in 1919, the 18th Amendment passed, starting a national Prohibition, which officially became law by January 16, 1920.

It wasn’t surprising then, that in the years leading up to the 18th Amendment, that covert gatherings in small towns such as Rockland would take place in speakeasys, which were nightclubs that sold liquor illegally. In the seafaring towns of Maine, bootleggers and smugglers could get the illegal liquor via Rum Row, a line three miles off the tip of Maine that ran down to the coast of Florida.

According to Rockwell, attics and basements used to be the perfect hiding spots for speakeasys and the cavernous attic room of 435 Main Street was used for exactly that purpose. Currently, all four floors of the building are in the process of renovation. As I walked up the stairs to the third floor, the walls began to tell their own story. Scrawling signatures on the plaster walls testified the presence of the partygoers in that era.

G.G. Rogers wrote “Big Night” on Aug. 25, 1917 and one can only imagine what the big night was. A birthday? Engagement? A grand old hooch-filled evening?

Fallen plaster from ceilings revealed wooden slats in most of the rooms and hallways on the third floor. Finally, we had reached the attic stairs. The spooky stairwell leading up was swimming with dust motes. On both sides of the walls leading up to the door, more signatures — hundreds of them — filled every available space. This was the graffiti of the 1920s, daring to let others know that they existed and yes, they were drinking illegally.

Once we reached the top — just like the movies — there was the door to the speakeasy with the little “knock knock” panel. You could almost hear the music inside and expect to see a burly fellow with a cigar clamped in his teeth squint one eye at you as he opened the panel.

Inside the large, rubble-filled attic, time stood still. Only two small sky lights let in diffuse light. The arched ceiling looked like ribs of a dead whale. Everything had fallen into total disrepair. That’s what happens when a speakeasy goes unused for nearly 100 years.

A few remnants of humanity still existed up there — a broken chair, an old water closet with pull chain and an industrial sink. The knob and tube wiring snaking the walls might have gone unused. Even though the speakeasy had electricity, the kerosene marks on the walls told a different story. Keep the lights as low and you won’t get caught.

This building used to the the Wise & Kimball Block owned by Iddo K. Kimball, which sold stoves and hardware on the first floor in 1853. But nothing I researched could tell me what became of this speakeasy and whether it was eventually busted or abandoned after Prohibition ended.

Many remember the building as the high-end kitchen accessories, the Store, before Sara Foltz sold it to Rockwell. According to Rockwell, she discovered hundreds of old “medicinal” bottles from Boston and Long Island stored in the building and has kept a large cache of them. The few remaining bottles Rockwell possesses have their own nudge-and-wink labels like Beef, Iron and Wine a “Nutritive Tonic”with 20 percent alcohol that “restores the natural vigor that goes with good health.” Another bottle labeled P&S Tonic, for physicians and surgeons claiming to be “an approved formula especially indicated in run down and weakened conditions.” A full tablespoon was recommended three times daily.

A few doors down on Main Street, the Thorndike building basement, another reputed speakeasy in Rockland, is also being renovated at the same time this spring. All I could see peeking in from the street side door was a big empty basement room, gutted to the studs. If there was ever any writing on the walls or remnants of its illicit history, it’s all gone now. Several attempts to reach the owners directly were unsuccessful, but I discovered through the Rockland Historical Society that in 1854 the Thorndike Hotel was built by William Thorndike, who happened to be a mariner, a merchant and an owner of stables.

He opened the hotel in 1855, with a a livery stable attached and charged only $1 a day for a room. According to Ann Morris’ historical booklet A Walk Along Main Street, the Thorndike Hotel was considered “a first class hotel...patronized by the large number of steamboat travelers and the public generally.”

It’s interesting to note that only a few short years after Maine banned the manufacture and sale of liquor, this particular hotel became popular. Was it because there was a secret basement entrance to the speakeasy? That’s what local rumors have long suggested. In 1937 (not long after Prohibition ended), the Thorndike Hotel was taken over by the U.S. Navy and the Coast Guard. The basement room was officially recognized as the Rainbow Room and became a favorite saloon for many in the area.

According to local historian Gil Merriam, when he was a boy working at the Strand Theater, everyone referred to The Rainbow Room as “The Passion Pit.”

People always say “if these walls could talk.” I imagine if they did, the sound would be of hundreds of people shouting their own names and the dates that they could be found carousing in back rooms that only a select few knew about. “I was here!” they’d say. And that’s all we’ll ever know before the carpenters come in and wipe away the past.

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States