Lincolnville's Little Andy: Moving through a rough patch with love and grace

Andy O'Brien and his mother, Tracee, are at Maine Medical Center these days, while Andy recuperates from a dose of chemo.

Andy O'Brien and his mother, Tracee, are at Maine Medical Center these days, while Andy recuperates from a dose of chemo.

Andy O'Brien.

Andy O'Brien.

Ed and Jack O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ed and Jack O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Maggie O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Maggie O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jack O'Brien, Andy's little brother. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jack O'Brien, Andy's little brother. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A mermaid graces the front steps of the O'Brien home in Lincolnville. Maggie gave it to her mother, Tracee, last Mother's Day.

A mermaid graces the front steps of the O'Brien home in Lincolnville. Maggie gave it to her mother, Tracee, last Mother's Day.

Andy O'Brien teaches his grandmother, Diane, how to play Mario Kart. (Photo courtesy of the O'Briens)

Andy O'Brien teaches his grandmother, Diane, how to play Mario Kart. (Photo courtesy of the O'Briens)

Andy O'Brien and his mother, Tracee, are at Maine Medical Center these days, while Andy recuperates from a dose of chemo.

Andy O'Brien and his mother, Tracee, are at Maine Medical Center these days, while Andy recuperates from a dose of chemo.

Andy O'Brien.

Andy O'Brien.

Ed and Jack O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ed and Jack O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Maggie O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Maggie O'Brien. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jack O'Brien, Andy's little brother. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jack O'Brien, Andy's little brother. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A mermaid graces the front steps of the O'Brien home in Lincolnville. Maggie gave it to her mother, Tracee, last Mother's Day.

A mermaid graces the front steps of the O'Brien home in Lincolnville. Maggie gave it to her mother, Tracee, last Mother's Day.

Andy O'Brien teaches his grandmother, Diane, how to play Mario Kart. (Photo courtesy of the O'Briens)

Andy O'Brien teaches his grandmother, Diane, how to play Mario Kart. (Photo courtesy of the O'Briens)

LINCOLNVILLE — On Saturday, I headed out to Lincolnville to visit with Andy O'Brien, because there's nothing better than hanging with a three-year-old boy, especially one who is known to be the sweetest kid around. But Andy was not home. He was at Maine Medical Center in Portland, at the Barbara Bush Children's Hospital, enduring a bad spell with the chemotherapy he received a few days earlier. His temperature was up, and he was miserable. An ambulance had transported him the night before from PenBay Medical Center to Portland, and his mother, Tracee, had gone with him.

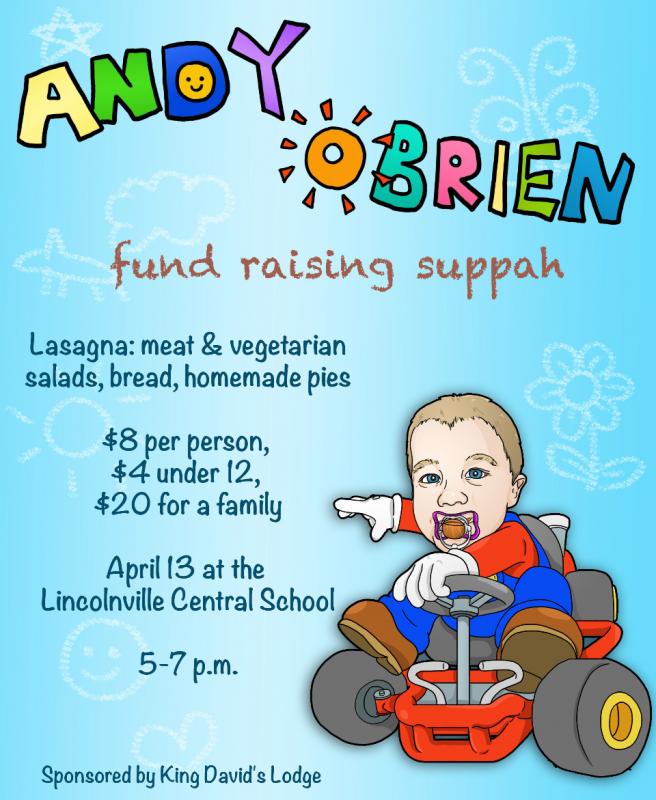

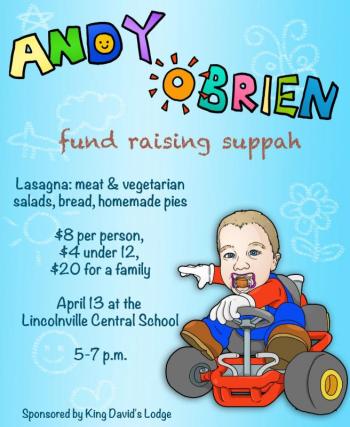

Dinner fundraiser April 13

The Masons of King Davids Lodge of Lincolnville have organized a meat and vegetarian lasagna supper with salad, Italian bread, pies and dessert.

It will be held Saturday, April 13, from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Lincolnville Central School, Rt. 235, just out of the Center, Rt. 52, ¼ mile from Petunia Pump; $8 for adults. $4 under 12 and $20 a family.

If you can’t make it, check donations or gas /gift cards can be sent to Edward and Tracee O’Brien, 537 Slab City Rd., Lincolnville, ME 04849.

The Masons are providing the food but are asking for desserts. If you can bring a dessert, please call or email Jackie Watts, history7@tidewater.net, 763-4504, so she can keep track of what's coming. Delivery time for desserts is 3 to 4 p.m. at LCS. A friend has organized meals for Ed & Tracee; this website allows people to sign up on a schedule.

Andy had a brain tumor in the back of his head. His parents, Tracee and Ed O'Brien learned that when Cheryl Milner, their daycare provider, called and told Ed that although Andy had eaten lunch, he was tired, and "seemed off." The tumor was removed, but as anyone familiar with cancer knows, what comes next is often the true ordeal.

Andy, born Nov. 15, 2009, had been mentioning earlier in February that something hurt, rubbing the back of his neck. When Cheryl called on Friday, Feb. 15, Tracee and Ed decided to take him to Waldo County General Hospital that afternoon. Doctors in Belfast wasted no time in sending Andy up to Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor. And there, doctors suggested, Boston.

A CT-scan and MRI later, it was evident that Andy had a tumor the size of his fist in the back of skull, and it was a rare form of childhood cancer.

"They were probably just as scared as us," said Ed.

In the matter of a few days, Andy and his parents were at Boston Children's Hospital.

The diagnosis referenced a blastoma, a word which Ed immediately took to the web to research.

"Then, I stopped," he said. "I didn't want to know. In the future, maybe. When it's all over. God willing."

Ed and I sat in the O'Brien's kitchen that Saturday morning, March 30. Lined with shelves of toys, plants and books, their home is full of life, young life. Maggie, a five-year-old sister to Andy, was busy blowing up balloons, fitting together a puzzle and inspecting an Easter basket. Her littlest brother, Jack, at 15 months, was grinning, climbing up on the table, in and out of his father's arms. Every once in a while, Jack would stand up beneath the table and whack his head. There would be a pause, but no outcry.

"You're ok, Jack, right?" asked Ed. "It's not a tumor, it's all good," he said, with wry, loving humor. We looked at each other, and though tears filled eyes, they were blinked away quickly, and we laughed. Because what do you do?

Ed continued to tell me the story of how a family bursting with vitality copes with Andy's illness. And how a community provides a web of support through the starkness.

When cancer walks into a home — any home, at any age — things are again never the same. Families who have endured this know the anxiety of not-knowing, and the abrupt departure from normal life. The every day concerns fall away as minor and almost meaningless.

And when you are 38 and 32, work fulltime jobs, and you have three young children, there is no time to dwell. It is high-intensity adaptation to first the terrifying news and then the medical realities (who knew that Ed and Tracee would have to suddenly learn how to give daily injections to Andy to keep his immune system strong? Who knew that Tracee would be beside her son 24 hours a day for months, again sharing with him her life force?) At the same time, they have two other children deserving constant care, affection and consistent normalcy. A new kind of normalcy.

"This spring and summer is going to be really intense," said Ed. An understatement.

Andy embarked last week on a series of five chemotherapy treatments consisting of five different drugs. They are harsh, and there will be no radiation, because medicine has learned that the longterm effects of chemo are less severe than radiation on a three year-old's fragile body.

The tumor in Andy's head was removed in February in Boston, by a rock star doctor, said Ed.

"He came into the hospital room, Alan Cohen, at 11:30 at night, in his Harvard sweatshirt," he said. That was a Monday night. Cohen, who was named No. 1 on the U.S. News and World Report ranking of pediatric neurosurgeons, scheduled the surgery for Friday morning.

"He was extremely familiar with this type of cancer," said Ed. "He told us he was going to a conference, and to go have fun."

The O'Briens did that. Diane, Ed's mother, went down to Boston from Lincolnville with Maggie. By that time, steroids had reduced the swelling around Andy's head and he was feeling better. They went to the top of the Prudential and ate as much pizza as a three-year-old could consume. They returned Friday for an eight-hour surgery, and Susan Stonestreet, the pastor of Lincolnville's UCC church, arrived. Tracee went into the operating room with Andy and with the anesthesiologist, they sang, "The wheels on the bus go round and round."

Three hours later, the anesthesiologist said, "It went beautifully, everything we wanted to see."

One hour after surgery Andy was awake and playing Angry Birds on the iPad.

"They scooped the thing out with entirety," said Ed.

Tracee lay in bed with Andy, in the pediatric intensive care unit, eyeing his blood pressure.

"She put her cheek on his cheek and his blood pressure just dropped," said Ed. "For Tracee, that was huge. As a mother, she finally felt she could do something."

Three days later, Andy was discharged, and he was off and running, the back of his head healing up.

Now, he is onto the next phase, which involves weekly doses of chemo, resting his body for two weeks in between the five treatments. That will last through June, with his parents giving him his daily shot.

"We're social workers, we don't know the medical field," laughed Ed.

Andy's stem cells will also be harvested, in keeping for the final hurdle: The last treatment will be a megadose of chemicals that will course through Andy's body, while he lies in an airlocked room for three to four weeks, away from germs.

"Then, God willing, he's done," said Ed.

Tracee, who grew up in Richmond, is a social worker for the state, Ed works at Harbor Family Services in Rockport. They are used to listening to the problems of others. When trouble came knocking on their door, the couple made a conscious decision.

"We are not going to keep this in," they said, according to Ed. "We're just going to put this out there."

In doing this, their support network has grown nothing but sturdier. It begins with the grounded and loving family of the Lincolnville O'Briens, and widens expontentially from there. The UCC church is always there. Their dear friend Michelle Kinney, who knows about medicine and reactions to it, lives across the street. There is an order of nuns in Portland praying for Andy. There is a Bhuddist monastery in Taiwan praying for Andy. And there are the friends on Facebook, around the globe, checking in with Ed and Tracee. A box of teddy bears arrived from someone in Vermont — "all these really sweet gestures," said Ed.

"It feels so powerful knowing that we're loved and that people are thinking about us. We are having a lot of uncertainty, with bills and beyond."

We talk about the craziness of medical bills that pour in when illness strikes. The bills stacked with exorbitant digits. Their meaninglessness when all the other factors come crashing down. We laugh about Andy and his place as the middle child in a family of three children. (Ed is also the middle child, between two brothers.)

"This is like the ultimate middle child stunt," he laughs again, with tears. "Andy and I are very similar."

I asked Ed what he might do the rest of that day, and the next, which would be Easter.

"I'm putting Jack to sleep for a two-hour nap, and I found a recipe for a pizza turnover," he said. "We will decorate eggs, and have facetime later on the iPads with Andy [Jack hugs the iPad and kisses his mother]. Tomorrow, we will put on new Easter outfits and go to church. We may go see him tomorrow."

Ed looks at me, and we talk about raging at the universe about things we can't control. But he is a sage man, who has nothing but love spilling from his heart. He says he tells the teens at work that some things just must be dealt with as they arrive.

"You can't yell at the waves because you can't tell the wind to stop blowing." And he delivers a huge kiss on the cheek of Jack, who is laughing in the arms of his father.

Editorial Director Lynda Clancy can be reached at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States