Maine’s red flag law goes live in February. What will that look like?

Law enforcement blocks the road leading to Schemengees Bar and Grille in Lewiston on Oct. 27, 2023, two days after a shooter killed 18 people. The shootings renewed calls to enact a red flag law, which allows family members to directly ask courts to take weapons away from a person at risk of harm. Photo by Emily Bader.

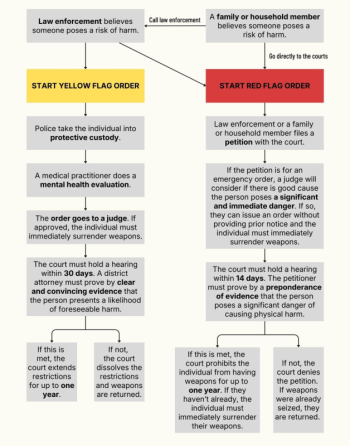

Law enforcement blocks the road leading to Schemengees Bar and Grille in Lewiston on Oct. 27, 2023, two days after a shooter killed 18 people. The shootings renewed calls to enact a red flag law, which allows family members to directly ask courts to take weapons away from a person at risk of harm. Photo by Emily Bader. A step-by-step look at Maine’s yellow and red flag laws. Graphic by Emily Bader for The Maine Monitor.

A step-by-step look at Maine’s yellow and red flag laws. Graphic by Emily Bader for The Maine Monitor. Law enforcement blocks the road leading to Schemengees Bar and Grille in Lewiston on Oct. 27, 2023, two days after a shooter killed 18 people. The shootings renewed calls to enact a red flag law, which allows family members to directly ask courts to take weapons away from a person at risk of harm. Photo by Emily Bader.

Law enforcement blocks the road leading to Schemengees Bar and Grille in Lewiston on Oct. 27, 2023, two days after a shooter killed 18 people. The shootings renewed calls to enact a red flag law, which allows family members to directly ask courts to take weapons away from a person at risk of harm. Photo by Emily Bader. A step-by-step look at Maine’s yellow and red flag laws. Graphic by Emily Bader for The Maine Monitor.

A step-by-step look at Maine’s yellow and red flag laws. Graphic by Emily Bader for The Maine Monitor.Maine’s new red flag law, which was approved by voters in November, is set to take effect next month, offering a new way to temporarily remove guns from people who appear to be suicidal or pose a risk of harm to others.

But details about how exactly the state is preparing law enforcement agencies, judges and the public for the new process are limited, and how it will work alongside Maine’s preexisting yellow flag law remains to be seen.

With about a month remaining before the law takes effect, the Maine Department of Public Safety has not yet finalized its procedures; the courts are creating the forms people will need to fill out to start a red flag process; and the group representing police chiefs has not organized any training for law enforcement.

The red flag law will take effect on Feb. 21, and will be on the books alongside Maine’s current yellow flag law.

While a yellow flag order can only be initiated by law enforcement, and requires that the individual be taken into protective custody and given a mental health evaluation, a red flag order can also be initiated by a concerned family member going directly to the courts, without a behavioral assessment. Both laws require a judge to evaluate evidence and approve the order before weapons are temporarily removed.

The director of a Johns Hopkins-based center that helps states implement red flag laws said it had not received any requests for assistance from Maine agencies as of early January. Lisa Geller, the director of implementation at the Center for Gun Violence Solutions, said the period before a red flag goes live is a “critical” time to set up infrastructure, get people trained and ensure that law enforcement, the courts and the public are ready to use the law on day one.

The Maine Department of Public Safety is leading efforts to implement the law, but department spokesperson Shannon Moss has said it is too early to provide details about what that looks like.

She noted in an email that “operational planning is still underway, and there are no finalized procedures to discuss at this time.” She added that “providing commentary now would risk being incomplete or inaccurate.”

The State of Maine Judicial Branch is responsible for creating the form that family members or law enforcement can fill out to start the red flag process. These will be available in-person at courthouses as well as online, spokesperson Barbara Cardone said.

The courts are “programming our systems to accommodate the new forms and orders,” she said, adding, “that is about all we need to do to prepare for the effective date.”

The state court system will be required to submit annual reports to the Maine Legislature, starting next year, that detail how many petitions were filed, whether they were approved or denied, and whether there were motions to terminate or dismiss them.

The Maine Chiefs of Police Association, which represents local law enforcement officials from across the state, has not yet conducted trainings or been involved in any discussions regarding implementation, said president Scott J. Stewart, the Brunswick Police chief.

“Each department and prosecution district will likely work on trainings specific to protocols they intend to follow as it relates to the statute,” he said.

While prosecutors are not directly involved in the red flag process, the Maine Prosecutors Association will attend any conversations with law enforcement “to stay informed on what is happening on the ground,” said Shira Burns, the association’s executive director.

Those meetings are still being scheduled, she said in early January.

Geller, from Johns Hopkins, said training for judges and law enforcement will be particularly important because “they are going to need to know not only what this is, but how it’s different from a yellow flag.”

Preparation should include posting clear information about the process online and setting up training sessions for state officials who will be involved in the various stages of the process, including judges and law enforcement officers, Geller said, adding that clinicians should probably also be included since they play a significant role in carrying out yellow flag orders. Unlike the red flag law, the yellow flag law requires a mental health evaluation.

Geller co-leads the National ERPO Resource Center, which launched in 2023 with support from the U.S. Department of Justice and provides training and technical assistance to government agencies implementing extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws, also known as red flag laws. Maine is the 22nd state to approve such a law.

“Maine hopefully should have a little bit easier time starting up this implementation because they already have the framework and infrastructure built around the yellow flag law,” she said.

The yellow flag law took effect in 2020, but it was not widely used or understood until more than three years later, after the 2023 shootings in Lewiston that left 18 people dead. Before the shootings, officers from 35 police agencies statewide had completed just 80 orders. In the two years and two months afterward, the law has been used to temporarily remove weapons more than 1,100 times, according to data provided by the attorney general’s office.

There wasn’t much direction in the early days of the yellow flag law, said Major Mark Dyer, the commander in charge of Sanford Police’s support services division.

The Maine Criminal Justice Academy, which certifies and sets training standards for all officers in the state, provided a mandatory, one-hour training about the yellow flag law on Zoom in 2020, according to Moss, from the state public safety department. The academy has provided additional training since then, including a mandatory, two-hour course on the yellow flag law in 2024.

“It was difficult for a while, just trying to figure out how this was supposed to work so we can do it right,” Dyer said.

One significant challenge was finding medical practitioners to complete the required mental health assessment. He said officers would bring someone into protective custody and take them to a hospital for an evaluation only to find “hospital staff won’t touch it because they don’t really know anything about it.”

In October 2022, the state contracted with the mental health agency Spurwink to provide the required assessments for yellow flag orders remotely. Previously, some hospitals had refused to do the evaluations out of concern that employees could face retaliation, the Portland Press Herald reported at the time.

Sanford police did not complete its first order until December 2022, but by the time of the Lewiston shootings it had completed seven orders — more than any other agency except the Maine State Police. Dyer credited then-Detective Colleen Adams with leading the charge to get the department familiar with the law and finding ways to streamline the process, such as preloading iPads with digital forms and creating checklists for officers.

As of Jan. 5, the department had completed 36 orders, one of the highest totals among agencies in the state.

Law enforcement officers will soon have the option of turning to the yellow flag law or the red flag law. Even when family members initiate a red flag order themselves, police will still be involved in the process of notifying individuals and securing weapons.

When they have the choice, Dyer said he believes his agency will continue to default to using the yellow flag law because of its extra guardrails: both because it requires that officers take an individual into protective custody to initiate an order and because they have to demonstrate a mental health concern to a judge before they can temporarily take someone’s weapons away.

Since the subject of a red flag order does not need to be in protective custody for a judge to approve it, Dyer said he is concerned about officers’ safety when serving notice of an order or executing a search warrant. He said he also appreciates that the yellow flag process includes a mental health evaluation.

“We know that there’s a mental health issue; we know that they’re a danger to themselves or others,” he said. “Then we’re able to secure them, put them in a safe place, like a hospital and at least, even if it’s temporary, get them in front of a clinician. Like yeah, ‘I see what you’re seeing. Let’s remove this person’s guns. Let’s try to get them some mental health help.’”

Proponents of the red flag law believe it is important to have an avenue that does not involve a mental health evaluation because violence is not necessarily linked to mental illness.

Sagadahoc County Sheriff Joel Merry said he also believes law enforcement will continue to use yellow flag orders instead of red flag orders because officers are more familiar with the process at this point. His department received intense scrutiny when Merry disclosed days after the Lewiston shootings that his deputies had twice attempted to check on the shooter but failed to make contact as recently as a month prior.

“I don’t believe you’re going to see significant changes in the way we’re doing business,” he said. “I think calls are still going to come in where people are going to report a family member or loved one or neighbor or whoever in crisis. Police are going to respond.”

Police will gather information and determine if a person presents a risk of harm. If they do, police will initiate a yellow flag order.

“A lot of work has gone into streamlining this process,” Merry said. “It’s working for them now.”

Family members will likely be more inclined to apply for a red flag order than law enforcement, he said, which is why he publicly supported passage of the law. Sometimes families may not want to go to the police out of concern that it will escalate a situation. The red flag law will instead enable them to ask a court directly to remove someone’s weapons and secure that determination before police get involved.

Data collected by the National ERPO Resource Center show that in other states with red flag laws where both law enforcement and family members can petition the courts, it’s mostly law enforcement officers who initiate the process, said Geller. Only Maryland saw about a 50-50 split between the two groups.

Regardless of who initiates a red flag order, law enforcement will still need to serve the order or execute a search warrant, a process Merry expects to look similar to a protection from abuse order.

In terms of the concern Dyer and others have raised about officer safety, Merry said law enforcement officers deal with potentially dangerous situations every day and are prepared appropriately.

“As law enforcement, we treat every traffic stop or every encounter with the public as if the person has a weapon,” he said. “Why is this more of an issue?”

Proponents of red flag laws have said that such laws are a critical tool for suicide prevention. Nearly 80 percent of all gun deaths in Maine in 2023 were suicides, according to data analyzed by Johns Hopkins University, compared with 60 percent nationwide. Maine also has one of the highest rates of gun suicide among older adults.

Supporters of the red flag law, including the Maine Gun Safety Coalition, have made the case that those closest to someone in crisis would likely be the first to notice concerning behavior, and the law will give them an option to quickly get dangerous weapons out of their loved ones’ hands.

While the law’s official effective date was December 18, 30 days after the governor ratified the referendum vote, it is “inoperative” until February 21, which is 45 days after the start of the legislative session, because it relies on funding in the governor’s supplemental budget.

The governor has said her upcoming supplemental budget will provide the funding necessary to implement the law.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit civic news organization. To get regular coverage from The Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.