Waldoboro native discusses how she has trained many on the frontlines of COVID-19 testing

EAST LANSING, Mich. — While the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the world, one Waldoboro native has stepped to the frontlines of the pandemic and trained numerous individuals currently working on COVID-19 testing.

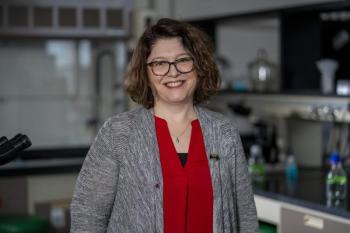

Dr. Rachel Morris, now a teaching specialist and and graduate program director at Michigan State University, volunteered to be a COVID-19 contact tracer and, through her teaching, prepared students for similar work.

Morris, who is also helping by sewing many face masks, attended a now defunct private Christian high school in Warren before earning from the University of Maine at Augusta an associate’s degree in medical laboratory science and a bachelor’s degree in biology.

She also earned a doctorate degree in biological sciences, with a concentration in microbiology, from Marquette University. Her postdoctoral research and training was completed through the University of Michigan Medical School (internal medicine and infectious diseases) and Michigan State University’s Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics.

Living in the Midcoast until the age of 35, Morris noted being a Mainer has influenced her life in a variety of ways, including some she likely does not even recognize.

“I guess I would say it has made me a strong person and an independent thinker,” she stated, while crediting her time at UMA as shaping her into the professional she is today.

The field of science has captivated Morris since she was a young child.

“I was always out in nature exploring things and doing experiments of one kind or another,” she said.

Interested in medicine but favoring bench science, she trained as a medical laboratory technician at UMA right after high school and worked at the Togus Veteran’s Administration Medical Center.

After pausing her education to have children and do some part-time tutoring and teaching, she returned to UMA to earn her bachelor’s degree in biology, believing she was going to be a high school science teacher.

Her advisor, Dr. Peter Milligan, asked her to join his new research lab. Morris was hooked on microbiology research and had discovered a new passion — teaching and conducting research. (Her areas of research interest at Michigan State include the microbial ecology of anaerobic wastewater treatment, the physiology and ecology of bacteria in low oxygen environments, diagnostic microbiology, and faculty development.)

After earning her doctorate degree, a requirement for her newfound passion, and postdoctoral training, she accepted a position on staff at Michigan State University in 2014. The job, she said, seems to tie all her experience together.

As an educator at Michigan State, Morris teaches pathology, molecular diagnostics, and writing, while serving as the graduate school program director for the university’s Biomedical Laboratory Diagnostics (BLD) program.

The program is tasked, according to Morris, with training individuals to perform human diagnostic testing in hospital laboratories, public health labs, and reference labs.

Many of Morris’ previous students, who are Medical Laboratory Scientists, are performing COVID-19 testing.

“To become a MLS, you need a bachelor's degree which includes a lot of science, lab classes, and math,” Morris detailed. “These rigorous courses include multiple classes in things like statistics, chemistry, microbiology, hematology, immunology, and molecular diagnostics. You must also complete a laboratory internship in an actual hospital lab setting that lasts about six months to a year. Most people who complete this training sit for a board of certification exam overseen by the American Society for Clinical Pathology, and they must complete continuing education to maintain their certification.”

Becoming a MLS requires an abundance of training, Morris noted, while adding she is very proud of her students.

“I taught them that the patient comes first, and they are out on the front lines living it right now,” she said. “There are now many types of tests for the virus on the market with different methodologies. My students are qualified to run them all, but some are designed to be run by people with less training than my students have. Some of my students oversee this testing, however, to assure that they produce quality results.”

Talk of contact tracers has been a recurring point of Maine CDC Director Dr. Nirav Shah’s weekday press briefings, where he discusses the latest pandemic updates in the state.

What exactly is a contact tracer and what are their responsibilities?

The volunteers work with local public health departments, Morris detailed, and talk to people who have been reported to have had contact with an individual that has tested positive for COVID-19.

“These people, who may now be at risk for COVID-19 themselves, need information,” she explained. “So, they are contacted, told that they have been in contact with someone with the virus, and provided with information for what they should do next. This whole process maintains the confidentiality of the person who tested positive and their contacts. In general, people are going to be asked to self-isolate and watch for symptoms. They are told what to do if they do have symptoms and are also provided with resources for any sort of help that they might need related to their situation.”

Thanks to her professional background, Morris decided to undergo training necessary to be a COVID-19 contact tracer in Michigan.

Despite completing the training, she has not had the opportunity to participate, as of yet, due, in part, to needing to assist her colleagues at Michigan State shift to virtual teaching.

“It has been quite a challenge for educators all over the nation to transition away from face-to-face instruction,” Morris said.

As the director of the graduate school program that offers three online degrees, Morris holds virtual instruction most semesters and virtual education is constantly on her mind, even before the pandemic forced virtual education to become more prevalent.

“I have also had some training in this area, so when the switch to remote learning happened — I had three hours from when I found out until my first online class meeting — it was pretty easy for me,” she stated. “But for others with less experience and for the students who didn’t sign up for that huge change, it was more difficult.”

As part of her work in assisting her colleagues shift to virtual education, she has answered questions, shared tutorials on using technology in teaching and helped lead a week-long workshop for colleagues moving entire programs to virtual learning for Michigan State’s summer term.

As a professor, Morris, naturally, is also tasked with helping her students adapt and cope with their educational, and life, experiences being altered by the pandemic.

“I will be getting additional training and continuing to provide help and guidance for my peers on the MSU faculty over the summer,” she said. “I give out advice to the broader community now and then on Twitter. I was pretty excited when the learning management system that we use asked if they could use some of my advice in their advertising materials.”

Morris noted she hopes to assist the local health department during the summer.

Though she has not yet been able to participate in the contact tracing program, she stressed it is vital that those who are qualified, and able to, participate as a contact tracer do so in order to control the virus and restore some sense of normalcy.

“Knowledge is power in this situation, especially until we have a treatment or vaccine,” she said. “We need to have enough testing and contact tracing to help isolate people who may pass on the virus to others. In this way, we can limit the spread of the SARS-Cov-2 virus.”

Speaking on why she opted to volunteer, Morris said it was a logical decision given her background.

“I volunteered because, while I don't do diagnostic testing anymore, I have been trained in things like medical confidentiality and patient interaction, and so it seemed a logical thing to do when the governor put out the call,” she said. “We all want to get our country running again, at least as much as possible. I want to do what I can to help.”

Asked to provide final words of wisdom amid the pandemic, Morris offered: “Wash your hands. Don't touch your face or other people. Listen to [Director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases] Dr. [Anthony] Fauci. Be kind.”

Event Date

Address

United States