The stony history of St. George

When I was a kid, some 60 years ago, I learned to swim at Wildcat Quarry, when three massive wooden crane masts were still standing. The last one, capped with an active osprey nest, recently toppled.

In the 1960s, the last working granite quarry, Flat Ledge, better known as Hocking granite quarry, near Clark Island village, closed forever and filled with water. I remember our family visiting that quarry, staring down at the workers way below, cutting stone. Pumps kept the big hole dry.

Today Flat Ledge is a private preserve. Wildcat, more recently called Atwood's Quarry, was once a popular swimming hole. Today, swimmers enjoy Long Cove Quarry and the salty quarry on Clark Island.

Most of the island, including two quarries, will soon be permanently conserved through a campaign by Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Nature has taken back much of Clark Island, but there's still plenty of evidence revealing an industrial past.

Besides cranes, commercial buildings and wharves, Clark Island included a village with a post office. Granite foundations remain to remind us, as does the nearby Craignair Inn, once a boarding house for quarry workers.

To find out more about our town in the "stone age," I contacted local sculptor and musician Steve Lindsay, who lives in what was originally a quarry worker's house. His interest in sculpting stone led him to interview surviving quarry workers in the 1980s, and he learned how to split granite using what’s called feathers (shims) and wedges, made of steel.

He has demonstrated granite cutting and talked about the industry at packed meetings of the St.George Historical Society. Granite, a silica rock that can be polished like glass, has great strength but can also be easily broken if mishandled.

Lindsay remembers stone cutters like John Olson, born in Lysekil, Sweden: "He showed me how to use the hand tools."

Quarrying here began in the 1830s, mostly involving Scottish and English immigrants, hence the hamlet called Englishtown.

At first, workers drilled a row of holes by hand, put wooden pegs in the holes with water, and covered them overnight. The swelling wood split the stone, hopefully in a straight line.

Later, wedges and feathers were used to split stone without having to wait. Some of the first quarrying took place on Mosquito Island, where a stone house is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Stone from Mosquito was used to build the lighthouses at Southern Island and Matinicus Rock.

For decades, granite was shipped on schooners, so island quarries were ideal for the trade.

"You needed access to water, granite being bulky and heavy. There were no trucks or railroads. You needed to get it on a vessel," said Lindsay.

When railroads were built, stone could be shipped from inland quarries. Granite continued to be quarried into the 20th century. What really brought the industry down was the advent of cement and steel for construction, and asphalt for roads.

By the 1940s, most quarries were closed. Today there is still demand for granite curbing, kitchen counters and landscaping.

Hocking Granite provided granite curbing for the United Nations headquarters in New York. Now, there are no working quarries left in St.George.

"There was tremendous pride in what you did," Lindsay said. "You were building the Albany post office. You were building the Buffalo City Hall, the Rockland post office and customs house."

Workers were highly skilled. When the state tried employing prison inmates to quarry granite on States Point (hence the name), it was a complete failure. The workers didn't have the skills that can take years to master.

That's why so many immigrants from Sweden and Finland came here, and Finnish names like Polky and Lehtinen, Swedish names like Skoglund and Ausplund, are carried on by descendants of stone cutters. Skilled Italian stone cutters also made their way to St.George.

Bicknell, a Scottish stone cutter's name, became the tool-making source for the trade, as Bicknell Manufacturing Company in Rockland.

Lindsay tells the story of Italian immigrants who were recruited by granite company thugs to help break a strike the moment they landed in New York, and were put on a train to Rockland.

The stone cutters union got wind of the scheme, and bought the men tickets for the train back to New York. Quarrying was rough, hard work. When pneumatic tools replaced hand tools, granite dust caused silicosis. Men died from it.

Hundreds of St.George men worked in the quarries for decades. Local historian Jim Skoglund, himself from a quarry family, said that nearly every family in town had at least one man working as a stone cutter, tool sharpener, supervisor, laborer.

When Flat Ledge was owned by Meehan Brothers, 50 railroad cars of granite were numbered, crated and shipped to New York City, in 1922, for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, in use today.

In 1925, stone cutters at Flat Ledge produced three million street paving blocks.

The late Albert Frederickson, born in Sweden in 1894 and a resident of Main Street in Tenants Harbor, remembered cutting "pavers." Lindsay talked with Frederickson, who was blind by that time, and asked about a record number of blocks cut in one day.

At first the old stone cutter was dismissive, but finally acknowledged he cut 306 pavers in a single day, for a total day's pay of $9.

Speaking of pay, the stone cutters formed a union to bargain for fair wages, and their union hall still stands in Clark Island, converted to a home. Granite tycoons who owned the quarries were ruthless employers, paying children 50 cents per day to work in the quarries. Men could earn as much as $5 per day, no benefits.

In 2020, almost all the men who cut the stone are gone.

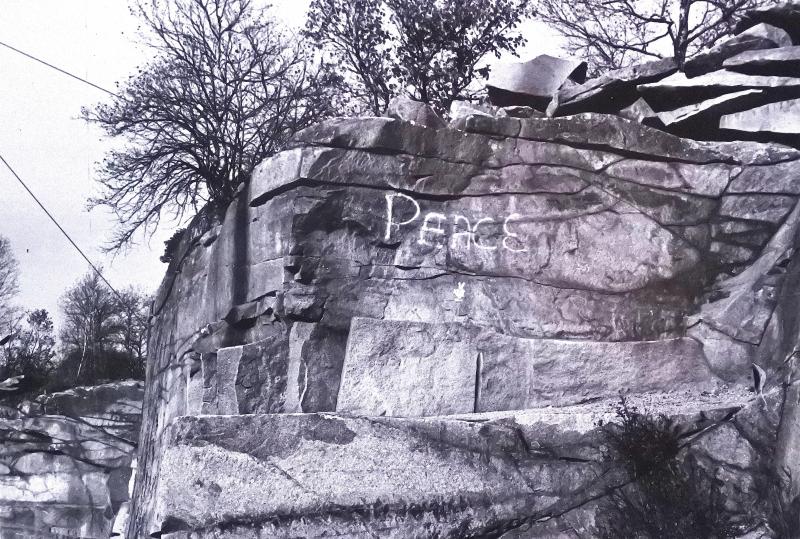

The giant pile of "grout," discarded chunks of Wildcat granite visible from Route 131 at Haskell Cove, is a permanent reminder of our industrial past. And the quarries, with their deep, clear water, continue to be a place to swim, sunbathe or, if you dare, jump from the high cliffs.

Steve Cartwright lives, writes and takes pictures in Tenants Harbor.

Event Date

Address

United States