Kristi Williamson heads back to India to work with sex trafficking victims

They come from Himalayan mountains and the floodplains of Bangladesh, or from the India countryside. Many are teens or children, some as young as 10, and they speak different languages, which means they cannot communicate with each other, and barely even with the police who have seized them from the brothels that dot the city streets of Kolkata (Calcutta). They are scared and scarred from forced prostitution, and confused about what lies next.

That’s where the skills of dancer, yoga instructor and movement artist Kristi Williamson come in.

She will travel to Kolkata this winter, just as she did last winter, to work with these girls, using paints, crayons, music and dance to lift them past the pain and terror, and create the hope of productive, healthy lives.

It is not easy in the port city of 4.5 million people, but there are hands that reach to help from within India, as well as across oceans.

Most in the Midcoast recognize Kristi as a yoga teacher, or performance artist. They know her as the daughter of schooner captain Ray Williamson and kindergarten teacher Ann Williamson — the Camden-Rockport High School graduate who brings opera houses, barns and parks alive with dance and music with her unique spirit.

But more recently, she has involved herself with California-based Tamalpa Institute, which was founded in 1978 by dance and expressive arts therapists. To Tamalpa, dance and making art is healing, and transformative — psychological and behaviorally. It is the nonprofit's mission to create a new paradigm for education, therapy and social action through a life-art process.

Kristi has taken the philosophy and methodology that she learned with Tamalpa in the Bay area to the grim shelters and halfway houses of Kolkata.

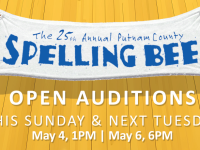

Kristi Williamson is holding her eighth annual yoga mala at High Mountain Hall, in Camden, Sunday, Jan. 10, from 1 to 4 p.m.

The New Moon Yoga Mala is the welcoming of the new year with 108 sun salutations.

She donates a portion of the profit to a different cause. This year, the money is going to the India project.

For more information, see Williamson’s Yoga Mala Facebook page.

“They are smuggled across the borders and made to work in the brothels,” she said, describing the young girls who have been enticed or deceived into the sex trade for the sake of desperately needed income for their families back home.

Sonagachi is the red light district in Kolkata, where 7,000 to 12,000 girls, boys, women and men are working in the sex trade. It is a complicated economic weave of those who are prostitutes by choice, and those who are forced into it.

It is the children and trade victims that private organizations are trying to rescue. They are the ones that Williamson is returning to work with when she flies back to India later this month. She will work with Laura Price, who runs the San Francisco-based nonprofit Blossomy, which emphasizes the use of expressive art and music in healing.

“Police, sometimes at the suggestion of anti-trafficking organizations, raid the brothels, and anyone who looks under the age of 16, they take to the shelter,” she said.

There, the girls rest behind bars. So they don’t escape and/or so their captors, or bosses, don’t come to reclaim them.

“It’s a jarring environment,” said Kristi.

She walks into it on a daily basis, face to face with anger and fear, and employees who are trying to educate the girls, with the hopes of a job someday.

The Sanlaap shelter that Williamson works is one of several established since the nonprofit’s founding in 1987. The organization rescues hundreds of girls each year from what it describes as “the mesh of sex trafficking.”

“I work with the highly traumatized, as well as others who have moved along,” she said.

The latter may be residents of the New Light shelter, in Kolkata, which operates: “from the terrace of a temple deep inside the red-light district of Kalighat, Kolkata, that offers comprehensive community development services. The project provides the children of sex workers a safe haven, particularly in the evening hours when streets are the most dangerous and the mothers are working,” according to that nonprofit’s website.

New Light has another residence, also in Kolkata, that is dedicated to healing and workshops.

The girls carry memories that most U.S. women can barely imagine, but it surfaces in their art. Some pictures they draw are of men engulfed in flames. They are the men they want to burn, the ones who dragged them away from their families.

There are pictures of hearts and fish and flowers, or flags of the countries they called home. And there is a picture of a mother and a child. The girl who drew it has nothing but longing to return home.

And there is a colorful picture of geometric shapes. The Bengali girl who drew it one said that the colors had been taken away from her and she just wanted them back inside her.

Kristi wrote in her Winter 2015 report about a girl she called the Soul Drawer.

“A young, small girl comes to sit at the edge of the teaching space. I remember seeing her watch from afar our first day together. She has a shaved head and worn clothing, mostly dressed like a boy. I ask her if she wants to participate. I can see she speaks no English, her eyes look down, she blushes and bobbles her head ‘no.’

“Intently, she watches the other girls dance and explore their bodies. When we move into the art I see her pining eyes gaze at the colorful abundant array of crayons and fancy thick clean white sheets of paper. I greet her with supplies and gesture for her to begin drawing. She looks around at the other girls and gauges the exercise, then begins. Gently, apprehensively, she starts to draw. Her hands grow in momentum, her one pointed focus deepens in intensity. She is now dancing, her eyes intent, her vision clear. Mindless, thoughtless, pure creation.

“Day Three she is now sitting in a chair in the teaching space near the music station. When we begin the art again her focus and intensity is contagious. At the end of class I ask if I can take a picture with her holding her drawing. She covers her face with the thick white paper, dissolving into it, forging her identity into this creative space of possibility and potential.

“For just one moment she is not her pain, not her memory, not a trafficked sex slave. She is simply the vastness of colorful spheres floating in space. She leaves. I hear news she tried to hang herself today but was unsuccessful. I look back at her image and notice a large black circle that I imagine holds the grief she experiences inside and a longing for a void to take its place. Although it’s horrifying what I have just heard, the

corners of my mouth raise as I see the bright colorful spheres she drew surrounding the black void.”

As the girls journey through the workshop, their thoughts shift and evolved.

Their drawings become less stick-like, and their dancing grows beyond the structured, formalized steps of traditional dance, or even that of the highly sexualized Bollywood, which they were conditioned to adopt.

Williamson’s workshops give the girls permission to express themselves, “however they were feeling,” she said. “They have no concept of how to create for creation’s sake. They have no idea there is something else possible inside them.”

And with dance, they are encouraged to freely move their bodies.

“They find new ways of expressing themselves through movement,” she said.

Williamson arms them with basic tools of mindfulness — use the breath, she says to them, just as she tells her yoga students in Camden and Rockland.

As they gain confidence, they also speak up.

“They speak in Bengali and then the assistant translates for me,” wrote Kristi, in one of her reports. “One girl spoke powerfully about her experience of the injustice of women and she wanted to burn all the pain disrespectful men have put upon her and all women. She was speaking of her strength as a woman and how the men are unable to perceive the female accurately.”

That point is important to Kristi, as she prepares to return to India. This year, she wants to go deeper into the scores — the exercises and workshops she conducts with the girls.

“I want to instill in them a sense of worth and empowerment, and that they know their souls are beautiful,” she said. “So that they understand they are whole and functioning women in this world, and not just seen for their sexual value.”

Reach Editorial Director Lynda Clancy at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com; 207-706-6657

Event Date

Address

United States