Orphaned and injured wild animals get TLC through Misfits Rehab

‘Manhattan,’ a recuperating opossum does not appreciate being woken from her afternoon nap. Photo by Kay Stephens

‘Manhattan,’ a recuperating opossum does not appreciate being woken from her afternoon nap. Photo by Kay Stephens

This chipmunk Peanut was found as an orphaned baby in an excavation site and given to Misfits Rehab. Photo by Kay Stephens

This chipmunk Peanut was found as an orphaned baby in an excavation site and given to Misfits Rehab. Photo by Kay Stephens

Chupacabra is a grey fox from Richmond and has a short coat due to illness. She is on medication and recovering. Photo by Kay Stephens

Chupacabra is a grey fox from Richmond and has a short coat due to illness. She is on medication and recovering. Photo by Kay Stephens

On June 26, 2019, Misfits Rehab took in a critical intake: an oppossum whose tail had been cruelly cut off and left for dead. They took him in and named him Percy, prompting news stories statewide. Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

On June 26, 2019, Misfits Rehab took in a critical intake: an oppossum whose tail had been cruelly cut off and left for dead. They took him in and named him Percy, prompting news stories statewide. Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

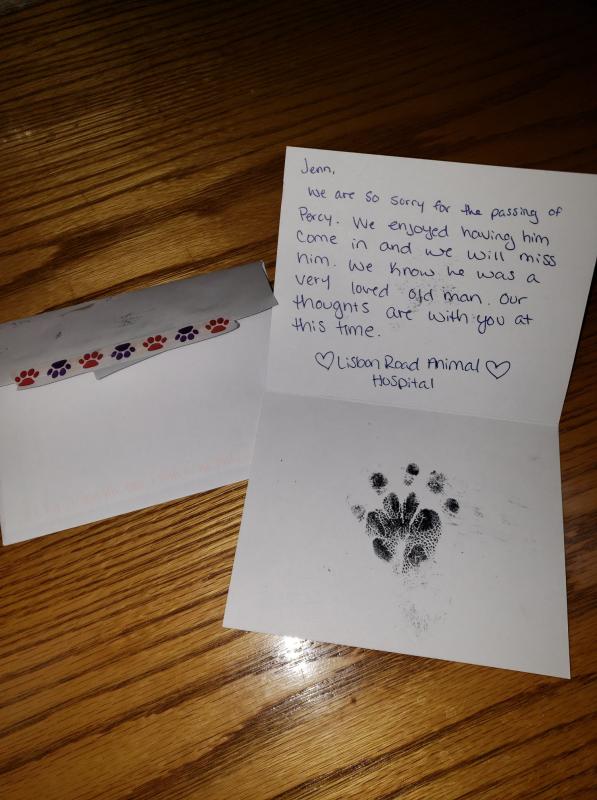

A recent Facebook post from Marchigiani: “Just when I thought I was starting to heal from the loss of Percy, I received this amazing card from the vet Had a hard time choking back tears... Lost the battle once I was alone...” Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

A recent Facebook post from Marchigiani: “Just when I thought I was starting to heal from the loss of Percy, I received this amazing card from the vet Had a hard time choking back tears... Lost the battle once I was alone...” Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

Marchigiani feeds their most recent intake, a small bat mealworms. Photo by Kay Stephens

Marchigiani feeds their most recent intake, a small bat mealworms. Photo by Kay Stephens

Wally, an orphaned beaver will have to be a resident at Misfits Rehab for the next three years because it needs to be under the care of its mother that long before it can function on its own. Photo by Kay Stephens

Wally, an orphaned beaver will have to be a resident at Misfits Rehab for the next three years because it needs to be under the care of its mother that long before it can function on its own. Photo by Kay Stephens

An unexpected devastation: this past week their chicken coop was destroyed by a fire, which also impacted the side of their house.The fire not only killed 11 of their chickens, but wiped out their supply of eggs, which fed the animals. One local supporter donated 15 dozen eggs. Photo by Kay Stephens

An unexpected devastation: this past week their chicken coop was destroyed by a fire, which also impacted the side of their house.The fire not only killed 11 of their chickens, but wiped out their supply of eggs, which fed the animals. One local supporter donated 15 dozen eggs. Photo by Kay Stephens

Stacks of food. Photo by Kay Stephens

Stacks of food. Photo by Kay Stephens

Bins of medicine. Photo by Kay Stephens

Bins of medicine. Photo by Kay Stephens

‘Manhattan,’ a recuperating opossum does not appreciate being woken from her afternoon nap. Photo by Kay Stephens

‘Manhattan,’ a recuperating opossum does not appreciate being woken from her afternoon nap. Photo by Kay Stephens

This chipmunk Peanut was found as an orphaned baby in an excavation site and given to Misfits Rehab. Photo by Kay Stephens

This chipmunk Peanut was found as an orphaned baby in an excavation site and given to Misfits Rehab. Photo by Kay Stephens

Chupacabra is a grey fox from Richmond and has a short coat due to illness. She is on medication and recovering. Photo by Kay Stephens

Chupacabra is a grey fox from Richmond and has a short coat due to illness. She is on medication and recovering. Photo by Kay Stephens

On June 26, 2019, Misfits Rehab took in a critical intake: an oppossum whose tail had been cruelly cut off and left for dead. They took him in and named him Percy, prompting news stories statewide. Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

On June 26, 2019, Misfits Rehab took in a critical intake: an oppossum whose tail had been cruelly cut off and left for dead. They took him in and named him Percy, prompting news stories statewide. Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

A recent Facebook post from Marchigiani: “Just when I thought I was starting to heal from the loss of Percy, I received this amazing card from the vet Had a hard time choking back tears... Lost the battle once I was alone...” Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

A recent Facebook post from Marchigiani: “Just when I thought I was starting to heal from the loss of Percy, I received this amazing card from the vet Had a hard time choking back tears... Lost the battle once I was alone...” Photo courtesy Misfits Rehab

Marchigiani feeds their most recent intake, a small bat mealworms. Photo by Kay Stephens

Marchigiani feeds their most recent intake, a small bat mealworms. Photo by Kay Stephens

Wally, an orphaned beaver will have to be a resident at Misfits Rehab for the next three years because it needs to be under the care of its mother that long before it can function on its own. Photo by Kay Stephens

Wally, an orphaned beaver will have to be a resident at Misfits Rehab for the next three years because it needs to be under the care of its mother that long before it can function on its own. Photo by Kay Stephens

An unexpected devastation: this past week their chicken coop was destroyed by a fire, which also impacted the side of their house.The fire not only killed 11 of their chickens, but wiped out their supply of eggs, which fed the animals. One local supporter donated 15 dozen eggs. Photo by Kay Stephens

An unexpected devastation: this past week their chicken coop was destroyed by a fire, which also impacted the side of their house.The fire not only killed 11 of their chickens, but wiped out their supply of eggs, which fed the animals. One local supporter donated 15 dozen eggs. Photo by Kay Stephens

Stacks of food. Photo by Kay Stephens

Stacks of food. Photo by Kay Stephens

Bins of medicine. Photo by Kay Stephens

Bins of medicine. Photo by Kay Stephens

AUBURN—Since 2002, Jennifer Marchigiani and her former husband have transformed an entire house into a M*A*S*H unit for injured and orphaned wildlife—the kind of animals that animal shelters can’t take—skunks, raccoons, fox, fawns, opossums, porcupines, beavers, chipmunks, squirrels, mice, even bats.

Marchigiani is a licensed as a wildlife rehabilitator who specializes in these animals and currently runs Misfits Rehab out of a home in Auburn. Her background stems from a lifelong love of wild animals as a child, including a multiple stints working at pet stores, as a vet tech, and as a zookeeper.

“You name it—anything smaller than a moose, we take it in,” she said. The only creature she doesn’t take are birds. Avian Haven, is known statewide for being the best bird rehabilitator.

Explaining where all of these “misfits” come from, she said: “People find animals in the woods, on road sides. A lot of the bats are found in people’s houses. Mice go into cars in the fall. And if the mom mouse runs away, people constantly bring me the nest of babies.”

Though the adorable factor is evident in her social media posts, the reality is that the job is far from glamorous. The distinct musk of wildlife is present in the basement where cages and enclosures line the walls surrounded by a work table covered in medicines, IV bag, pet food—even a bowl of wriggling meal worms—a snack for bats.

But, it’s the hours that make this volunteer job a true labor of love.

This winter, she is caring for 17 or 18 animals, but that number balloons in the spring and summer, when more animals have their babies.

“Every day we clean and feed the animals twice a day,” she said. “When we get a nest of babies that have to be fed every two hours round the clock, there’s no time for sleep— for anything,” she said, adding she receives help from her friends, volunteers and her former husband. “That’s when it gets crazy—when you have a three litters of six animals. By the time you’re done with a two-hour session, you got to start all over again.”

Marchigiani’ is one of 53 volunteer wildlife rehabilitators who operate out of their homes in Maine. In Waldo county alone, there are six rehabilitators, including Avian Haven. The best way to find out who takes in which kind of animal and where is through the Maine.gov website

“If you go through that website, it shows by county rehabilitators in the area,” she said. “And if you are tech savvy, go to Animal Help Now website or download the app on your phone and wherever you are, it will show you where the nearest wildlife rehabilitator is. If you’re in Auburn, you know I’m here, but if you’re on a family vacation in Massachusetts and find a gull with an injured wing, it will show you exactly where to take the animal.”

Every day, 365 days a year, the animals all need food, medicine and bedding. Marchigiani has smartly set up a donation widget with every Facebook post she makes of an animal, but even though she receives donations through Facebook and through yearly donation drives, it’s never enough.

“I was really nervous this year when we did our books and we discovered we had $15,000 in credit card debt for the animals,” she said.

Asked if there is a point where financially, this operation cannot sustain itself, she answered: “Well if you tell me, I’ll always make it viable. But the reality is we normally run between $5,000 to $10,000 in debt, and this year, we’re beyond that.”

To date, her highest profile guest was an opossum named Percy, a critical intake, who had his tail cut off by a Rumford man in 2019, who was facing a summons for animal cruelty before he was hit by a car weeks later and died.

“Percy was in the hospital three times for surgeries,” she said, noting that she’s got at least three veterinarians on speed dial.

Percy was taken to Misfits Rehab, where Marchigiani and a friend built him a special enclosure in the basement, complete with cat towers, a giant hamster wheel and a poster of a female opossum.

At the time of this interview, Marchigiani revealed that Percy had just passed away two days earlier. She visibly tried to contain her emotions while discussing it.

“He was at the end of his life span, and had congestive heart failure,” she said. “They only live four years. Everybody loved him. He’d had such a rough life.”

In the time she has been doing this, Marchigiani has learned to “let the animal go,” both emotionally and literally, when, the rehabilitation is complete, and they are physically released back into the wild.

She has been bitten by four different animals that were tested positive for rabies—but it comes with the territory and she has had her rabies shot.

Rescuing a critical intake is also a special skill.

“If you’re amped up, they will be stressed; but if you’re calm, it will go a long way to calm them down in a high-stress situation,” she said.

The other grim side to being a rehabber is knowing when to put an animal down.

“People see the cute pictures on Facebook and they express they want to have access to animals the way I do, but what they don’t see is if an animal is not in shape to be operated on and we can’t do anything more for it, we have to let them go,” she said.

To learn more about the animals she’s currently caring for visit Misfits Rehab Facebook page.

To become a wildlife rehabilitator visit: www.maine.gov.

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States