This Week in Lincolnville: Hard Times

I’ve developed a habit of listening to cable news all day long. It’s the way I filled the house with voices after Wally’s voice was gone. Now it’s just automatic: start the day with Morning Joe, end it with Rachel Maddow (if I’m still awake) with a slight diversion at 6 p.m. for Maine news and Lester Holt, or if visiting Don, CNN.

There’s a comfort in those familiar voices. Before this period in my life, I loathed a TV playing in the background of daily life. That never was going to happen in my house.

Until it did.

With the passing of time silence doesn’t bother me as much, but by now I’m hooked to the story these talking heads tell, and still check in throughout the day. The latest Covid numbers, what iconic figure just died, still more never-before-seen footage of the Capitol insurrection, and above all, the doom and gloom about to befall us. That would be the slide into autocracy and of course, climate change.

Across town my counterpart is tuned to Fox and hearing a somewhat different story line, but every bit as rote as mine. We’re each in our own propaganda bubble, the place where we’re comfortable. And we each believe the story that we’re hearing is the truth.

Oh, they try to cheer us up with feel-good stories of 9-year-olds collecting toys for poor kids, but I’m not fooled. Any kid with caring parents would do the same. It’s hard to escape the truth no matter which side we listen to: we’re going down an awful path to doom.

But since I also spend a good bit of time sifting through the old letters and journals that Lincolnville people wrote in the past century, my worry about the end of the world as we know it is tempered. Every era has its struggles and the one we’re living through is no exception.

Some 20 years ago I began interviewing Lincolnville people about their lives. They told me stories of their childhood, of their parents’ lives, and their own as young adults. I had a goal of writing about the whole of the 20th century, but after 9 years of work on the book I decided to call it done at 1950. Someone else can write the second half!

Here are three excerpts from Staying Put in Lincolnville, Maine: 1900-1950 from the 1940s:

CALENDAR

MONDAY, Jan. 3

School Committee, 6 p.m., LCS

TUESDAY, Jan. 4

Library open, 3-6 p.m., 208 Main Street

WEDNESDAY, Jan. 5

Library open, 2-5 p.m., 208 Main Street

Planning Board., 7 p.m., Town Office

THURSDAY, Jan. 6

Broadband Committee, 6 p.m., Town Office

FRIDAY, Jan. 7

Library open, 9-noon, 208 Main Street

SATURDAY, Jan. 8

Library open, 9-noon, 208 Main Street

EVERY WEEK

AA meetings, Tuesdays & Fridays at noon, Community Building

Lincolnville Community Library, For information call 706-3896.

Schoolhouse Museum by appointment, 505-5101 or 789-5987

Bayshore Baptist Church, Sunday School for all ages, 9:30 a.m., Worship Service at 11 a.m., Atlantic Highway

United Christian Church, Worship Service 9:30 a.m. indoors, masked or via Zoom

“Every night, just after dark, Raymond Oxton drove the length of the Atlantic Highway, from Bullock’s Hill at the Northport line to the Camden line, illuminated by just his parking lights. Raymond was a Civil Defense warden, and he was checking on his neighbors. All windows facing the Bay had to have blackout shades in place after dark. If he found so much as a sliver of light showing he’d stop the car and knock on the violator’s door. The blackout was serious business during the war years in Lincolnville. Like all Civil Defense wardens Raymond was trained to watch out for suspicious activity and/or persons and to report it immediately.

“On the other side of town at 10 Collemer Road, Eileen Young dropped what she was doing whenever she heard a plane approach and ran outdoors. She scanned the sky until she spotted the aircraft, then matched its silhouette to a Civil Defense guide she carried with her. Next she phoned the Civil Defense office to report what kind of plane it was, what time and the direction it was flying. A program to train English pilots caused local poultry farmers, including Eileen and her husband, Bradford, a real headache. The pilots were learning to fly low over a target, and those planes roaring overhead panicked the hens in everybody’s barns. The birds would pile up in the corners and could suffocate. After enough complaints the pilots were sent to a higher altitude.

“Bessie Dean was the busy mother of three young children during the war years, but she was a Civil Defense volunteer as well. Bessie learned to drive an ambulance and to administer first aid. She trained regularly to respond in case the town was attacked.

Large, hand-cranked sirens were stationed at strategic points around town. The children in the Youngtown neighborhood were frightened by the eerie sound whenever Clyde Young tested the siren at 367 Youngtown Road.

“An attack on Lincolnville wasn’t as unlikely as it seems from this distance and with the benefit of hindsight. In fact, because of its location on Penobscot Bay the town was as likely a target as any on the coast, probably not for attack, but as a landing place for German nationals bent on espionage and sabotage. A well-known incident at Hancock Point near Mount Desert Island in 1944 involved the landing of two German agents from a U-boat, sent to spy on the American armaments industry. The men were eventually captured after taking a taxi to Bangor, then making it all the way to New York City by train.”

And for Mary Louise Eugley, a young wife expecting her first baby, the war brought a different challenge:

“The trip to Camden had been all planned out ahead of time. Mary Lou Eugley’s father-in-law, Irvin, promised her they could make it no matter what. She believed him, but as the spring wore on, or rather mud season wore on, Mary Lou felt twinges of doubt. She’d never seen so much mud. Pennsylvania, where she came from, roads were paved and there were sidewalks. The Eugley farm, like every other place in Lincolnville, seemed awash in mud—muddy driveways, muddy dooryards, muddy, rutted roads.

“The baby was due at the end of April, and both Irvin and her mother-in-law, Agnes, kept reassuring her that by then the roads were usually drying out. They’d be able to get to the Camden Hospital when her time came. Still, as the end of the month neared, Mary Lou couldn’t see much improvement. She just hoped the car wouldn’t sink to its running boards like some she’d heard about.

“And now it was time. She’d held off waking up her in-laws as long as possible, but finally there was no doubt. The baby was on the way. Irvin had gone out to start the car in the dark, and Agnes was taking the suitcase, the one Mary Lou had packed days and days ago. She stood at the window, watching Agnes, faintly lit by the little slits of light coming from the blacked-out headlights, and thought for the thousandth time—if only Jenness could be here! It was hard enough to be pregnant and now getting ready to give birth, but to be apart was just too much.

Her husband of barely a year was on the other side of the world, an Army signal corpsman in New Guinea. They’d missed most of the first year of their marriage together, and now he was going to miss the birth of their child. Self-pitying tears threatened to start if she kept thinking these thoughts, and this was no time for that. She pulled on her coat, though she hadn’t been able to button it for ages, and stepped out the door.

“Boards were laid across the yard to bridge the mud, and Mary Lou teetered on them. Her balance wasn’t too good lately. If her foot slipped off, she’d be ankle deep, and have to walk into the hospital with a shoe full of mud. This baby couldn’t be born too soon for the expectant mother! Agnes was sitting in the back seat, and Irvin was holding the door for her. “You’ll be more comfortable in the front,” her mother-in-law told her. Mary Lou settled in the passenger seat, grateful she didn’t have to maneuver into the back seat. Irvin started slowly down the driveway, keeping the wheels on the high ridges between ruts, and Mary Lou closed her eyes to concentrate on something other than the labor pains that were coming periodically.

“Hard to imagine how a little innocent flirting with a soldier on a train could lead to this middle-of-the-night ride over muddy Maine roads. Jenness had been so handsome in his uniform; he told her he was bound for Bethlehem, Pennsylvania for the Army Specialized Training Program at Lehigh University. That wasn’t far from her hometown, and before they parted he had her phone number. One thing led to another and when he had a leave at the end of his program he invited her to come home with him to Maine.”

78 years ago, 24-year-old Sgt. Frank Slegona found himself in Germany; these are his words in a 12-page letter to his wife after the war ended in April 1945. As he wrote he knew the war in the Pacific still loomed over the soldiers who’d just defeated Hitler.

“It was that Sunday that I was supposed to meet you at Tessie’s house that we finally did get the bad news. Our sergeant told us that we were alerted and were not to leave the barracks, and here I had been all set to see you and my mother once more. It sure was a bitter disappointment for all of us. No one hardly spoke a word for hours afterward . . .

We left by trucks at 1 a.m. to a rail depot, at the depot we were met by a large brass band which played all sorts of patriotic music. We arrived at the 42nd St. ferry in Weehawken at about 3 a.m. . . . I soon recognized the place . . . only a 20 min. walk from there to where you were waiting for me. I got a big lump in my throat when I thought of how disappointed you would be when you finally realized I wasn’t coming. I was so close to you and yet so far away, I was wondering how long it would be before I would see you again and perhaps maybe never. I felt like an old beaten down man that night.”

Finally able to write an uncensored letter, he continued to describe what he saw.

“a small place called Hurtgen Forest where one of the bloodiest battles of this war was taking place. We could hear the booming of our big guns. . . . I knew that it would be a matter of hrs. before I’d be up at the front lines. We unloaded off the trucks & marched through about 3 miles of mud to a place just behind the lines & there we were assigned to different companies. I was assigned to a heavy weapons co. . . . The next day after spending a sleepless night we marched off to the front. I was loaded down with rifle ammunition and hand grenades. We were all scared stiff, on the way we saw dead Germans scattered all around and wounded men being brought to the rear. Some were all bloody & messed up others unconscious etc. We all were plenty scared but we were yet to learn the real meaning of fear.”

Frank returned home on furlough before being shipped out to the Pacific theatre. Then in early August atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki bringing about the surrender of Japan, and the end of the war. Frank and thousands of other U.S. troops were discharged and went home for good.

In 1951 Frank and Cyrene moved their family, which now included five-year-old Cyrene, to 112 Youngtown Road, Lincolnville, Maine.

Frank wanted to forget about the war and urged his wife to destroy all his letters, which she reluctantly did. But not the twelve-page letter; she kept it hidden for many years in a hosiery box in her drawer until the day her husband was ready to recall his experiences.

So yes, between Covid, the climate, and political shenanigans 2022 seems pretty grim. But so was watching for submarines off the coast, sending husbands, sons and yes, daughters too, off to fight in a horrible war. And so was missing a young husband about to become a father.

And by the way, Lincolnville lost three men in World War II: Aubrey Connors, Samuel Ripley, and Maynard Thurlow.

I have copies of Staying Put if you’re interested. Call, 789-5987 or email.

Booster Clinic

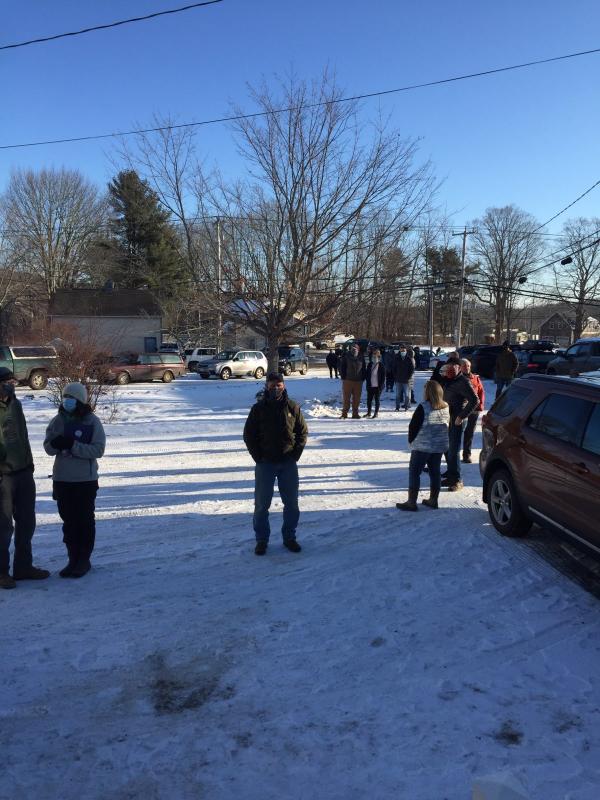

The town, in collaboration with North East ambulance, held a free Covid booster clinic at the Community Building last week. Of the 200 doses that were available some 180 were given out as the line snaked through the building and reached out to the road. According the Maine CDC map, 81% of people in zipcode 04849 are vaccinated; 04849 includes Northport as well as Lincolnville.