Belfast man journeys to Vietnam during its 50-year anniversary of national reunification

College students at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum interviewed Mike Hurley about his experiences during the years of the Vietnam War. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

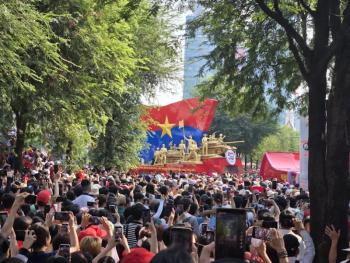

College students at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum interviewed Mike Hurley about his experiences during the years of the Vietnam War. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley) A military float passes by in the big parade celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war with America. Hurley said this was as close as he could get to the parade. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

A military float passes by in the big parade celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war with America. Hurley said this was as close as he could get to the parade. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley) A college lecture at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum. On the left on top of the pictures, the description reads "International organization about Vietnam in coping with the aftermath of the war." (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

A college lecture at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum. On the left on top of the pictures, the description reads "International organization about Vietnam in coping with the aftermath of the war." (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley) College students at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum interviewed Mike Hurley about his experiences during the years of the Vietnam War. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

College students at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum interviewed Mike Hurley about his experiences during the years of the Vietnam War. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley) A military float passes by in the big parade celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war with America. Hurley said this was as close as he could get to the parade. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

A military float passes by in the big parade celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war with America. Hurley said this was as close as he could get to the parade. (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley) A college lecture at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum. On the left on top of the pictures, the description reads "International organization about Vietnam in coping with the aftermath of the war." (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)

A college lecture at the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum. On the left on top of the pictures, the description reads "International organization about Vietnam in coping with the aftermath of the war." (Photo courtesy Mike Hurley)Mike Hurley, a longtime Belfast resident, business person, former mayor and council member of the city, has called himself “a student of the Vietnam War” since he was a young man. He was drafted in 1971 but was not eligible to go to Vietnam since he did not pass the mandatory physical exam.

Since then, he has wrestled with the war all his adult life.

For over 50 years, Hurley has studied and contemplated two primary questions about the war: “Was it all a waste? Did anything good come out of it?”

History remembers the Vietnam War as the longest conflict in history and the most unpopular war of the 20th Century. It resulted in nearly 60,000 American deaths and an estimated four million Vietnamese deaths. The war caused significant political and social divisiveness within both countries.

For some Americans, the war is still deeply felt and continues to shape their lives.

Hurley’s decades of studying several aspects of the war have included veterans’ narratives of their experiences, discussions with family members who lost loved ones in active duty, research, viewing documentaries and reading countless publications about Vietnam's history, war and culture, and presently a current read of Robert McNamara’s memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam.

But after years of studies and personal debate, he never had the opportunity to visit the country where the Vietnam War was fought. Until Spring 2025.

When Hurley learned that Vietnam was going to celebrate its 50 year anniversary of the Reunification last April, he knew it was a “big deal” and time to begin making travel plans.

“I’m going go to Vietnam," he told himself. "I was itching for a real adventure and at 74 I felt like physically I could still make the trip without needing my hand held."

“On April 5, I rolled out solo to catch a flight to Istanbul and connect on to Hanoi, 22 hours each way," he said. "I spent more than 30 days making my way to Saigon, now known as Ho Chi Minh City, and made it back to Belfast 36 days after leaving town.”

Hurley was in Saigon for the celebration on April 30 commemorating the 50th anniversary of National Reunification Day, an occasion that honored the historic victory in 1975 when the Vietnam People’s Army freed Saigon, leading to the unification of the North and South under the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

“I went to a bunch of parades where I was lucky to get within 100 people deep," he said. "For the final big parade, I bought a small step-ladder to see over the crowds. I was the only Westerner in a sea of Vietnamese. I found that when you walk down the street with a ladder people will talk with you."

He was impressed during and after the anniversary celebrations about how the Vietnamese deeply love their country and are filled with patriotism.

Hurley recalled two unexpected experiences that triggered emotion and reflection.

When he stood at the gates at the Independence Palace in Ho Chi Minh City, best known as the site where the Vietnam War ended, he “had real eye contact” with Vietnamese veterans. No words were spoken.

Another time, an older woman about his age gave him what he described as a long cold look.

“Not everyone can forget and forgive,” he said.

His travel itinerary was aimed to fulfill his desire to see the whole country from north to south. He traveled by plane, car, sleeper buses, train, bicycle, numerous boats, motorcycles, and a lot of footwork.

Hurley traveled south by train in “a rattling and jerking sleeper car," 12 hours overnight to Hue where the Tet Offensive had a climactic confrontation and 18 hours from Hue to Saigon or Ho Chi Minh City. He journeyed all down the coast with beautiful views.

"Most people never travel alone," he said. "I have done it a lot but around day 26 I was really yearning for a long conversation in English. Not speaking the language was hard but every single person was nice and helpful every time. Google translate was my friend."

At the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, Hurley met a triple amputee who stepped on a land mine 20 years after the war was over.

He was also interviewed at the museum by five college girls from Saigon University. One of the questions they asked him was what he did during the war.

Afterwards, he wondered if they could have endured what their ancestors did.

The tour of the tunnels of Cu Chi, also in Saigon, and which were an immense network of connecting tunnels underground, left another indelible mark in his travel journal.

The tunnels were used by Viet Cong soldiers as hiding spots during combat, as well as serving as communication and supply routes, hospitals, food and weapon caches and living quarters for numerous North Vietnamese fighters.

“I visited the tunnels where people lived, fought from and which we were never able to secure. I would never want to try and outwork or out improvise the Vietnamese,” said Hurley. “What I saw is that having fought, sacrificed, and suffered for as long as they did and especially years of horrific combat the good thing that came out of it all is that Vietnam is free, proud and united.”

Now, Vietnam is in the midst of an economic building boom. He said that construction crews, including women, work into the middle of the night.

"They are a thriving, happy country and I am really happy for them," he said.

After 36 days it was time for Hurley to begin the trek back to Maine.

"I was ready to come home, see my patient wife, get back to work.”

However Hurley believes that "Vietnam is still in my head."

"I thought I was done but who knows? Never say never.“