Waldo County: Why does it matter who's judge of probate court?

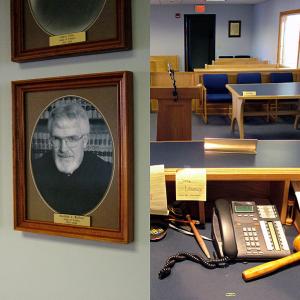

In the Waldo County Probate Court. Left: a portrait of challenger Randy Mailloux during a previous term as probate judge from 1997-2004. Right: Presiding Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley's view from the bench. (Photos by Ethan Andrews)

In the Waldo County Probate Court. Left: a portrait of challenger Randy Mailloux during a previous term as probate judge from 1997-2004. Right: Presiding Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley's view from the bench. (Photos by Ethan Andrews)

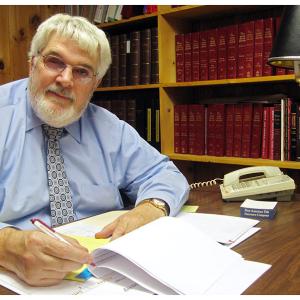

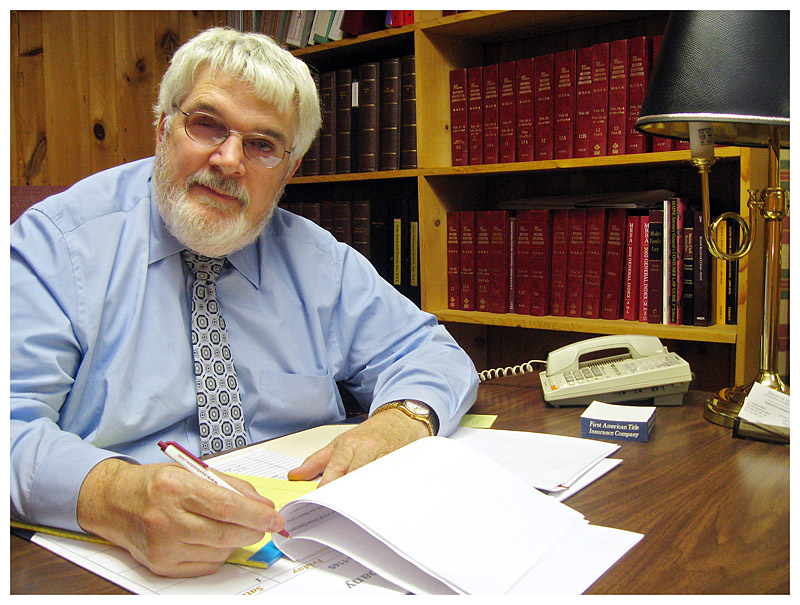

Former Waldo County judge of probate and current challenger Randy Mailloux in his Unity office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Former Waldo County judge of probate and current challenger Randy Mailloux in his Unity office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley has been campaigning by bike for reelection. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley has been campaigning by bike for reelection. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

In the Waldo County Probate Court. Left: a portrait of challenger Randy Mailloux during a previous term as probate judge from 1997-2004. Right: Presiding Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley's view from the bench. (Photos by Ethan Andrews)

In the Waldo County Probate Court. Left: a portrait of challenger Randy Mailloux during a previous term as probate judge from 1997-2004. Right: Presiding Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley's view from the bench. (Photos by Ethan Andrews)

Former Waldo County judge of probate and current challenger Randy Mailloux in his Unity office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Former Waldo County judge of probate and current challenger Randy Mailloux in his Unity office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley has been campaigning by bike for reelection. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Waldo County Judge of Probate Susan Longley has been campaigning by bike for reelection. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

BELFAST — During her campaign for a third term as Waldo County judge of probate, Susan Longley of Liberty has been fond of telling voters that Election Day will be their opportunity to “judge the judge.”

The clever line plays on what we might imagine judges do, but in the courtroom Longley has shied away from hard judgements in favor of the process of mediation, much to the chagrin of her current challenger for the bench — attorney Randy Mailloux of Belfast, who believes a judge should judge and no more.

The two have a history of sorts. Mailloux served as Waldo County’s judge of probate following appointment by Gov. Angus King in 1997 to complete the term of Howard Barrett Jr. That appointment lasted until 2004, when Longley defeated him at the polls.

Both held the position for roughly the same number of years, and both have witnessed aspects of what they describe as each other’s shortcomings: Longley when she inherited Mailloux’s court, and Mailloux as an attorney in the years since.

But personal contests aside, this year’s race for judge of probate shows what may be one of the clearest contrasts of styles Waldo County residents will see on the ballot. What may be less clear to some voters is why it matters who presides over the probate court.

“The fact is, people don’t necessarily know what probate is off the top of their heads, but most are likely going to be affected by it at some point in their lifetime,” said Aaron Fethke, a Searsport attorney who ran against Mailloux in the Republican primary and now serves as his campaign manager.

Probate deals with the administration of wills, estates, trusts, guardianships for children and adults who require a guardian, and adoptions and name changes, among other functions falling broadly under the category of family law. Often these can be handled by the registry of probate, but some number of cases each year are contested, which is where the court comes in.

Fethke said he didn’t necessarily like the idea of running against a fellow attorney, but said there was a feeling among members of the bar that the court had strayed from proper procedures in a way that was defeating due process.

While Fethke and Mailloux expressed qualms about procedures within the court, the crux of their concern has been with Longley’s preference for mediation over litigation, which has extended into the courtroom and, they say, led to delays in court appointments of attorneys.

“Everybody thinks attorneys are these big, bad, evil dudes,” said Mailloux recently. “Our purpose is to guide people through the legal system. And for most people, [the legal system] is too complicated to understand.”

Within this system, he said, each of the players serves an important but limited role.

The judge’s job is to make an impartial decision based on the law and on the evidence presented, he said. To this end, Mailloux contends that Longley has short-circuited the established, and inherently adversarial, process by pushing for mediation when parties are entitled to a court appointed attorney.

"She will tell you that we offer the mediation,” he said. “But when the person in the black robe is sitting up there and tells you as a pro se litigant — a person who doesn’t have any experience in court and doesn’t have a lawyer — that mediation is available and that may be a good idea for you to do, that becomes more than offering it. It becomes a suggestion that, in that position of authority, is very close to an order.”

Longley said she has been a strong advocate for mediation in the family law court because parties, in effect, resolve their own problems and are less likely to leave with a grudge.

Someone who goes into a case angry, is more likely to be stubborn and irrational, she said. But when a mediator listens and accepts that person’s point of view, things calm down and an opportunity for a win-win situation emerges.

“[A person might say] Oh great, I’m not all wrong, and if I’m not all wrong, maybe she’s not all wrong either,” Longley said. “And then things get clicking.”

In contrast to a judgement handed down, she said, the resolution is more likely to be something that both parties can live with.

Mediation also costs less, and Longley said the savings goes both to the citizens passing through the court and the county, which foots the bill for court-appointed lawyers and/or mediators.

Asked for an figure on the average cost of a case tried by an attorney versus one resolved with a mediator, Longley said $2,000 for the attorney as compared with $200 for the mediator.

“A tenth as much,” she said. “And if it goes to litigation, it’s my honor to be there.”

From her comment, she is clear that litigation is not her first choice.

“People aren’t getting anywhere fighting,” she said. “The litigation tool is a valuable tool; it’s not the only tool in the modern day court.”

Mailloux said he is not opposed to mediation and would make it available. “But it’s not the judge’s job to push it so much,” he said, noting that he is opposed to offering it once a trial has begun.

“My view is that the judge is the decision maker. By the time it gets to the judge, trying to work it out should be done,” he said. “A judge’s job is to make decisions.”

Here he feels that Longley has overstepped her role by advocating for those who have fewer resources in the name of “leveling the playing field.” Once a judge has done that, he said, it’s hard to return to an impartial position.

Mailloux acknowledged that mediation can save money, but said it can also “bridle justice” by denying a court-appointed attorney to someone who should have one.

Given that private practice attorneys are leading the charge to take back the judge’s seat, a logical question would be, "To what extent is the race about money?"

Both Longley and Mailloux acknowledged that any move toward mediation over litigation is going to take work away from lawyers, but neither felt that was the point. By the same token, the bench does not benefit the judge in any obvious financial way.

The position paid just over $30,000 in 2011, which Longley said is almost as much as she made in her first job out of law school.

A judge of probate in Maine must have a law degree, but does not need to be a practicing attorney. Longley had a private practice briefly after earning her law degree, but comes primarily from a teaching background.

Mailloux has been in private practice for 34 years and currently has offices in Belfast and Unity.

If elected, Mailloux’s partner, Jeremy Marden. would be prohibited from trying cases in Waldo County Probate Court to avoid a conflict of interest. But Mailloux said this wouldn’t be a major issue as many Waldo County residents live closer to another county seat than to Belfast.

In a 2010 article in the Maine Law Review, Peter L. Murray, a Portland attorney and Harvard Law School professor, argued against allowing attorneys to practice while serving as judge, even in another county, as it creates complications.

“A lawyer opposing a probate judge acting as lawyer in a contested matter must be aware that his adversary may be his judge in another matter,” he wrote.

Mailloux sees his ongoing practice — and here he emphasizes the word “practice” — as an advantage he holds over Longley.

“Just because I own a hammer doesn’t make me a carpenter,” he said by way of example. The hammer, here, being a law degree.

Longley, by contrast sees her detachment from private law practice as a benefit that allows her to dedicate all her energy to being a judge.

Like it or not, she’s taken the court in a direction it hasn’t been before — one in which the metaphor of a law degree as a hammer probably wouldn’t apply.

She likened her role to an observation she made while working with refugees in Africa, that when a child would fall down in the dust and cry, the mother's approach was simple and pragmatic.

"Essentially when families come in, it's not that different," she said. "My job is to dust them off, get them organized and send them back into the community."

Both Longley and members of the Mailloux campaign have pointed out the dramatic differences between their respective views. But on Longley’s campaigning line, they would probably agree. On Election Day, the citizens will indeed judge the judge.

A hope expressed by both candidates is that they will also know what they’re voting for.

Penobscot Bay Pilot reporter Ethan Andrews can be reached at ethanandrews@penbaypilot.com

Campaign websites:

Event Date

Address

United States