Union herbalist/farmer faces $100,000 lawsuit over ‘common’ trademark

The product at the heart of the lawsuit: Kathi Langelier’s original Fire Cider No. 9 brand, before she was ordered to change the name. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The product at the heart of the lawsuit: Kathi Langelier’s original Fire Cider No. 9 brand, before she was ordered to change the name. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

Kathi Langelier, owner of Herbal Revolution Farm & Apothecary in Union. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

Kathi Langelier, owner of Herbal Revolution Farm & Apothecary in Union. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The farm in Union where Kathi Langelier grows many of the herbs for her tonics, extracts and tinctures. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The farm in Union where Kathi Langelier grows many of the herbs for her tonics, extracts and tinctures. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

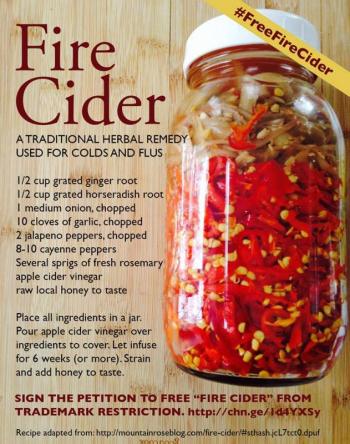

An example of what herbalists refer to as fire cider, much like people know the common products salsa and marina. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

An example of what herbalists refer to as fire cider, much like people know the common products salsa and marina. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The product at the heart of the lawsuit: Kathi Langelier’s original Fire Cider No. 9 brand, before she was ordered to change the name. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The product at the heart of the lawsuit: Kathi Langelier’s original Fire Cider No. 9 brand, before she was ordered to change the name. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

Kathi Langelier, owner of Herbal Revolution Farm & Apothecary in Union. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

Kathi Langelier, owner of Herbal Revolution Farm & Apothecary in Union. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The farm in Union where Kathi Langelier grows many of the herbs for her tonics, extracts and tinctures. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

The farm in Union where Kathi Langelier grows many of the herbs for her tonics, extracts and tinctures. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

An example of what herbalists refer to as fire cider, much like people know the common products salsa and marina. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

An example of what herbalists refer to as fire cider, much like people know the common products salsa and marina. (Photo courtesy Katheryn Langelier)

UNION — This was supposed to be an exciting summer for Katheryn "Kathi" Langelier. She'd just moved to a new house and farm in Union, ready to start a new phase of her life and ongoing business, Herbal Revolution Farm & Apothecary. An herbalist for more than 20 years, Langelier has foraged for herbs on the Maine coast, fields and forests. She also organically raises herbs in her garden for her micro one-woman business, making small batches at a time. When she first started, she would hand-label her extracts and tinctures and peddle them at farmer's markets, and later, sell them online through Etsy.

Her business has grown since 2009 with an expansion of her product line and a new website. Everything had been going fairly well except for one irritating snag. Since the 1990s, she'd been using the term "fire cider" for one of her products. According to herbalists, fire cider is a term as generic as the word salsa. For more than 30 years, fire cider has come to mean any herbal remedy that is spicy, vinegar-based and generally includes hot peppers, horseradish, onion, garlic and vinegar.

"I use a blend of vegetables and herbs that are combined with raw organic cider vinegar along with horseradish, onion, garlic, ginger, turmeric and habenero pepper," she said. When Langelier decided to formally brand and label her Herbal Revolution Fire Cider No. 9 in 2012, she did not even consider taking out a trademark on the name because it had been in general use by other herbalists.

However, in March, 2014, multiple business owners were told by Etsy that their online shop would be shut down if they didn't change the name of any products using the term "fire cider."

Langelier learned that Massachusetts-based herbal company Shire City Herbals had trademarked the term in 2014 and was putting legal pressure on small businesses around the country to cease using that term.

"I was angry," she said. "I thought it was unjust and deceitful. Fire Cider is a well-known tonic the herbal community created by Rosemary Gladstar in the '70s, but I didn't have the financial resources to fight them, so I changed the label to ‘Fire Tonic No. 9.’" However, in marketing her product, she would often hashtag it on social media as #firecider to provide instant context into what the product actually was.

The other two farmers, Nicole Telkes of Austin, Texas, and Mary Blue of Providence, R.I., were also told to change their product name, but they refused.

Word soon got out among herbalists around the country that this was rapidly becoming a David vs. Goliath trademark situation, very similar to the legal wrangling between the Vermont farmer who fought to keep his "Eat More Kale" t-shirts and branding against the objections of corporate food chain Chick-fil-A, which argued the slogan was confusingly similar to their "Eat More Chikin" slogan. (The Vermont farmer won to keep his trademark.) Soon after, a national grassroots petition began to urge the U.S. Trademark Office to cancel the trademark on the term "fire cider," claiming it had been used by multiple businesses since the 1970s.

More than 10,000 people have signed a Change.org petition against the trademark and 120 herbal teachers, stores,and manufacturers have come out in opposition to the trademark, with their logos displayed on the website www.freefirecider.com. There is also an active boycott of Shire City Herbal's fire cider product.

Langelier signed the Change.org petition, but she did not participate in a larger boycott. "I had my own business to attend to," she said. "I didn't have time for that. Besides, I thought it would be a conflict of interest to boycott a product that I myself, was selling."

In response to that petition and boycott, Shire City Herbal filed a civil lawsuit against Langelier and the two above-mentioned farmers in April 2014 seeking damages of $100,000 for lost business due to the defendants' alleged activities.

Langelier, who complied with Shire City Herbal's name change, thinks this lawsuit is because some businesses stopped working with Shire City Herbal, once they learned about the trademark issue and sought out Langelier's product instead.

"I never contacted any of Shire City Herbal's contacts. They sought me out," she said. "A lot of herbalists and small businesses work hard and from the heart. And I think that's what separates small businesses from large businesses."

Telkes, Blue and Langelier are represented by attorneys from the Augusta law firm Verrill Dana in both the trademark petition and the new civil lawsuit.

"Words that are the name of a product itself (like "Fire Cider" or "Bloody Mary") are not trademarks, so others are free to use them to describe or identify their goods," said the defendants' lawyer, Rita Heimes. "There are mechanisms in place for the public to help the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office correct an error like this when it allows a generic term to be registered. It's unfortunate that the registrants took the more aggressive step of suing Mary, Nicole and Kathi in federal court just because they are standing up for everyone else. We are honored to work with them to free "Fire Cider" so farmers and others can continue to use it as they always have."

Langelier offered the following advice for small business owners who are thinking about branding unique products: "As small businesses, we do our best to try to make sure no one else has a similar name and to create something as unique as possible." She recommends making a paper, photo and electronic trail of any branding term an entrepreneur comes up with as supportive evidence the moment they put the product on the market in case a similar legal situation as hers should arise.

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States