The Camden-Rockport Rock Road: Quarries, Community, and the Legacy We’re Still Building

I have been promising myself and others to write about the Rock Road for at least five years, but each time I start, I get so entangled and entranced by some new layer of its history that I never finish. This will have to be an incomplete account, because unfortunately, we may have run out of time, as a section of the road is proposed for removal.

In 1999, after the Camden-Rockport Bicycle and Pedestrian Committee (now the C-R Pathways Committee) helped secure grants to improve the road for use as a year-round, paved, multi-use pathway, a 3–2 vote on the Rockport Select Board removed the trail from consideration in what was described by Camden Herald editors as “squeaky wheel democracy.”

The Board, in 1999, agreed to spend $5,000 determining whether the Town’s rights to the road were full fee ownership or simply an easement. They were sympathetic to concerns from neighbors at the time not wanting to radically alter the road by paving it, but everyone agreed it was a public way, well used by the public, and that it should stay that way.

What happened after that is not clear, but I’ve served long enough on the Camden Select Board to know that a Select Board vote doesn’t mean something will actually happen. Staff and Select Board turnover, changes in attorneys, loss of institutional memory, and sometimes strongly worded threats whispered by private property owners can all make the difference.

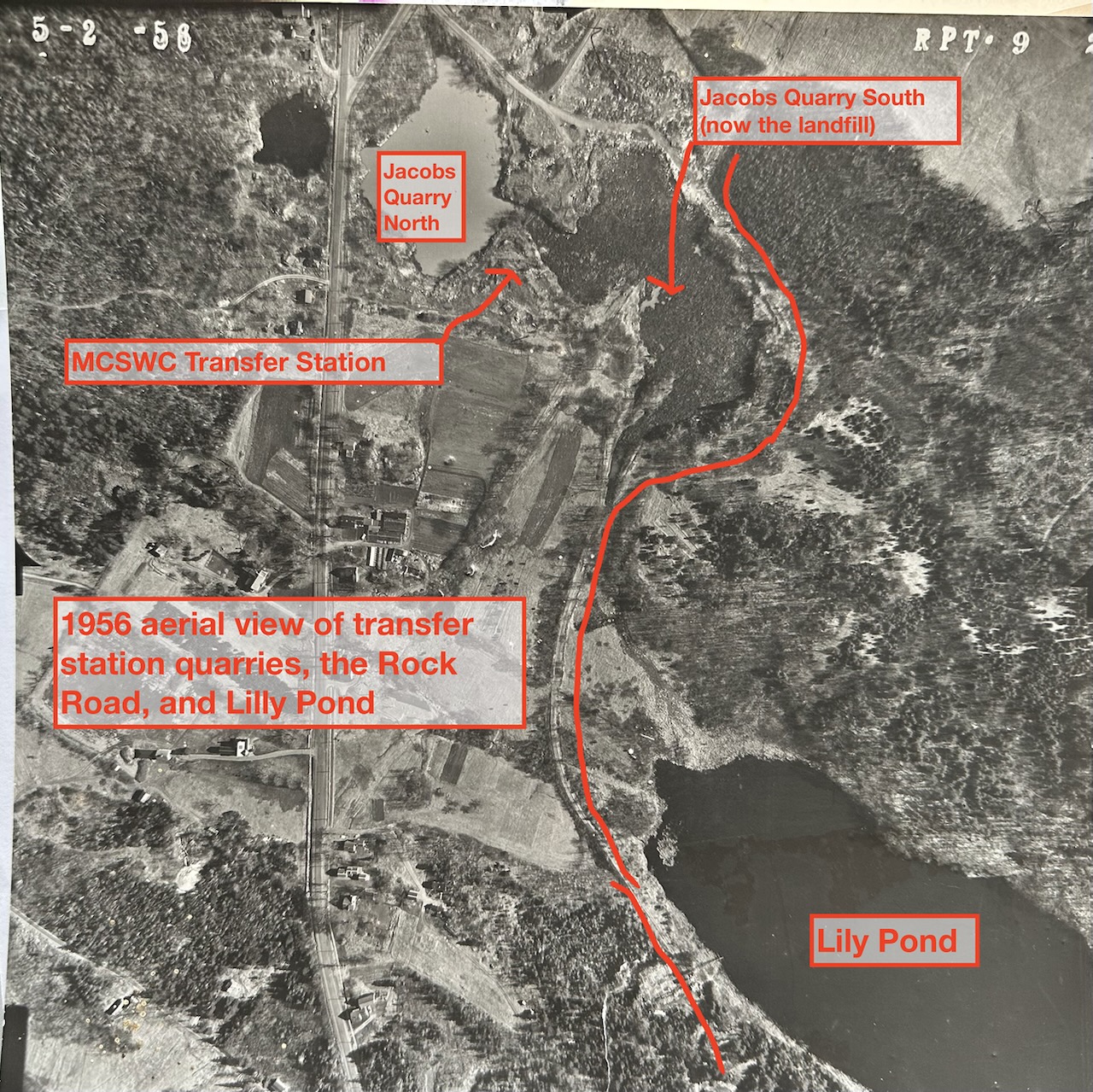

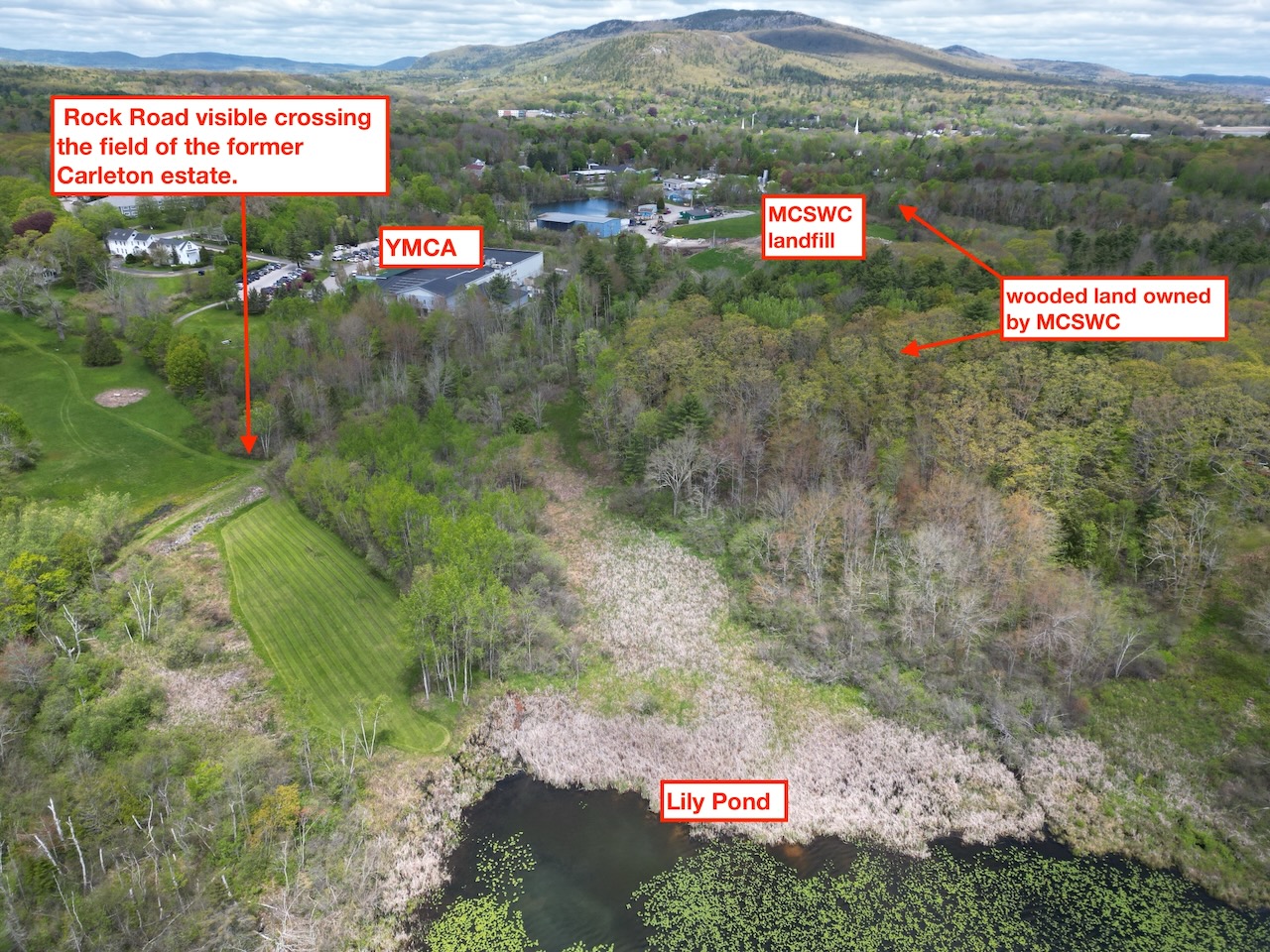

And at the time, some people just couldn’t understand why anyone would want to ride their bike or walk past polluted Lily Pond and a quarry dump that was filled with water and somehow always on fire. Today, things are very different, and it’s pretty easy to see why former Town Manager Roger Moody urged residents to “look 30 years down the road” — envisioning the capped landfill and former quarries as a 25-acre recreational hub, a future “Central Park” for Camden and Rockport.

In the 1990s, the vision for the Jacobs Quarry/Lily Pond Trail — linking Camden and Rockport villages, the YMCA, and neighborhoods — gained real momentum. Residents imagined their children biking safely to school, families strolling on Sundays, and a car-free route between towns.

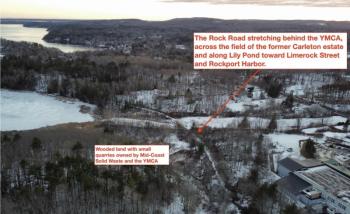

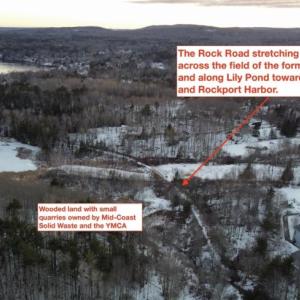

The old quarry roads connect Limerock Street in Rockport with Limerock Street in Camden. The path does not have formal signage but can be accessed by parking at the YMCA and walking around the back of the building to the left to a little opening in the grass. There is also a formal pathways easement throug the woods along the edge of the field (but that has not been marked or used). Turning right will take you toward Rockport Village, left will take you behind the landfill and out to Linden Lane in Camden. There is also room to park along the side of the road there, near the intersection with Limerock Street.

The old quarry roads connect Limerock Street in Rockport with Limerock Street in Camden. The path does not have formal signage but can be accessed by parking at the YMCA and walking around the back of the building to the left to a little opening in the grass. There is also a formal pathways easement throug the woods along the edge of the field (but that has not been marked or used). Turning right will take you toward Rockport Village, left will take you behind the landfill and out to Linden Lane in Camden. There is also room to park along the side of the road there, near the intersection with Limerock Street.

Image courtesy: Camden-Rockport Pathways Committee

The site was deemed ideal for the relocation of the YMCA in part because of the trail and proximity to Lily Pond; Camden voters approved land purchases in the Greenfield Subdivision to make the connection possible on another section of former quarry road; and the towns even received hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant funding.

Well, 30 years later, that future is here. The landfill is partially capped, Lily Pond has recovered, and the Rock Road — already built, already resilient — is openly used as a footpath, beloved by walkers, bikers, skiers, and wildlife watchers. The corridor is visible from the air and deeply ingrained in community life.

Horses carry quarried stone with wagons to Rockport Harbor. Photo courtesy Camden-Rockport Historical Society

Rockport Marine Park, where remains of kilns have been restored and artifacts

Rockport Marine Park, where remains of kilns have been restored and artifacts

from the quarry era brought in to display. (Lynda Clancy photo)

When I was a kid, my dad briefly rented an apartment in Rockport Village and we were frequent visitors to Rockport Marine Park, where some of the last remaining kilns have been preserved. Some of my earliest childhood memories involve tossing rocks through the fence to see if we could hear a reaction from the dragon my dad told us was rumored to be living inside. Our imaginations swirled.

It is good for us to think about the past from time to time, to imagine what life was like, how things were built, and all the stories that surround us. The kilns in Rockport Harbor are such a stark contrast to the high-end housing and fancy yachts dominating the landscape. I can’t help but think it’s good for us — the rough edges, the grueling labor, the centuries-old roots of a people who blasted metamorphic rock out of the ground and burned it in kilns so hot that even water couldn’t put out the flames.

As a kid I never thought about what was involved in keeping the kilns, the park, or the locomotive there, but today I know that the entire thing is the result of generations of people who had a vision. They acquired, preserved, and protected public property, connecting us to both the past and the future.

But the history of those kilns can only be understood by taking a walk along the same routes that carried the rock. Walking along the elevated stone, you can instantly feel the history, the sense that you’re walking in the footsteps of people who toiled, sacrificed, lived, and died — all with stories that depended on the Rock Road.

The Legal and Limestone Foundations of the Rock Road

The earliest settlement documents for the Town of Camden — which also included Rockport — made two things clear to aspiring landowners: Everyone had to help build roads, and no one was allowed to have quarries or export limestone.

Samuel Waldo didn’t want the competition, and he knew there was a rich vein of it running between Camden and Thomaston. Starting in 1768, there was a 50-year prohibition on anything to do with limestone.

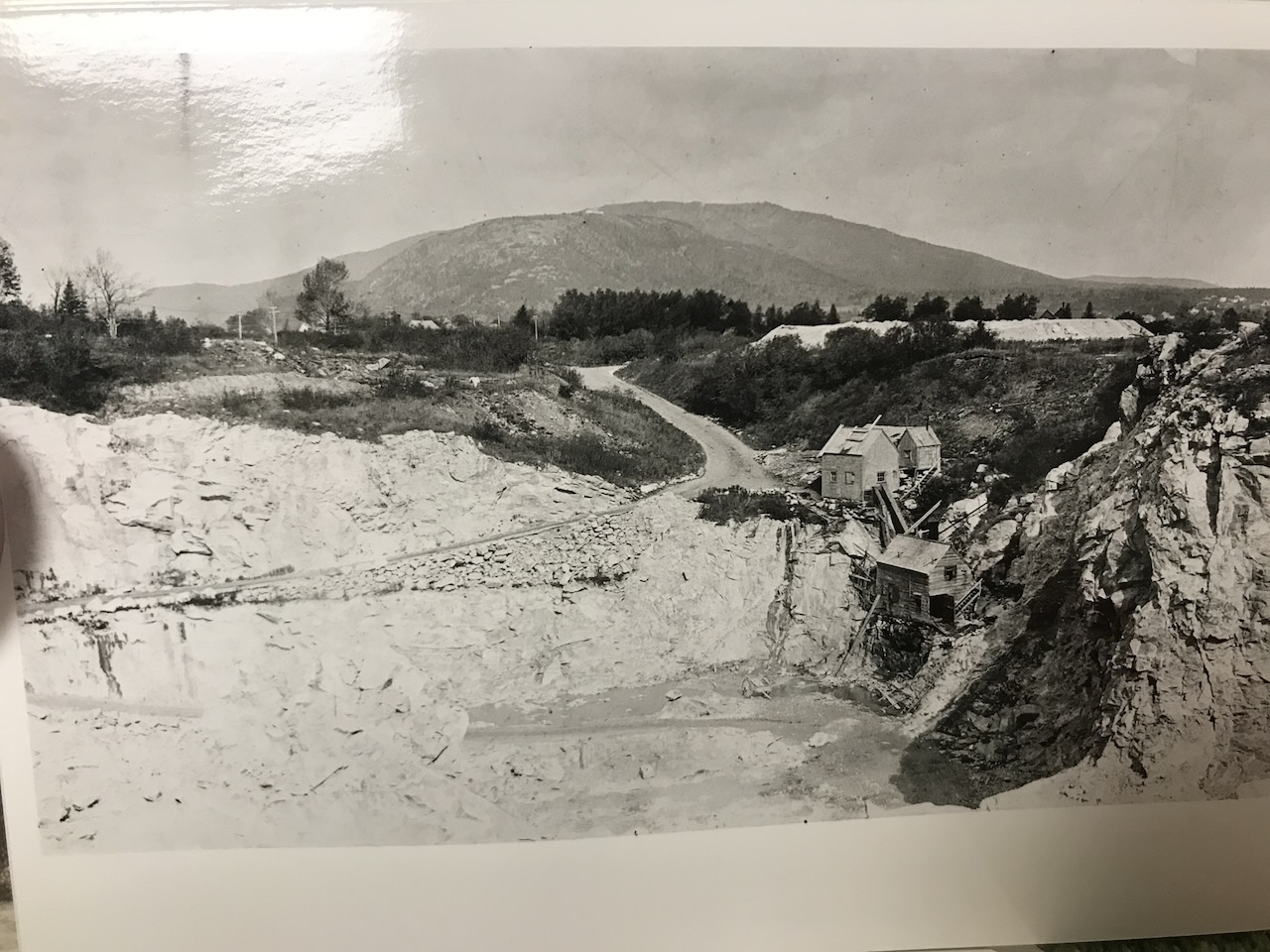

A view of Jacobs Quarry taken from similar vantage point as the top of today's construction debris landfill.

A view of Jacobs Quarry taken from similar vantage point as the top of today's construction debris landfill.

A view of the northern lights from the top of the capped portion of the landfill looking toward Mt Battie. Taken with permission.

A view of the northern lights from the top of the capped portion of the landfill looking toward Mt Battie. Taken with permission.

When that moratorium ended, landowners wasted no time. Enough limestone was extracted to create some of the deepest holes in the country, including Jacobs Quarry, now the transfer station, which was once 250–300 feet deep. The North Quarry (now open water, visible from Union Street) and the South Quarry (today the construction debris landfill that looks more like a mountain) were connected by a shallow gut, now filled in. That’s where all the colorful recycling containers are.

By the 1850s, the quarry lands around what we now call Lily Pond were owned in common by families whose names still echo through Camden and Rockport history: Emery, Young, Fletcher, Thorndike, Thurlow, Crocker, Brown, Jones, Burgess, Carleton. They shared quarries, haul routes, and stone.

Disputes arose, and in 1856 the Supreme Judicial Court appointed commissioners to divide the land fairly while preserving the vital roads and rights-of-way. Their survey formally recognized the Rock Road, a three-rod-wide (49.5 feet) stone haul road linking the quarry properties to Lime Rock Street in Rockport Village.

Here is the precise language from the Commissioners’ partition:

“And we assign & set out for the benefit of all the parties interested in the premises, before described, roads as follows, to wit: Beginning at the southwesterly corner of land set off to George Emery; thence north 60° east, one hundred forty six rods along the lines of lands set off to Emery & Young, to stake & stones at corner of land set off to Thorndike; thence north 74½° east, twenty rods & twenty links to Lime Rock Street. The foregoing is the northwesterly line of said road, which is known as ‘Rock Road,’ and is three rods wide.”

This is what a lot of the overburden rock looks like that was used to make the rock road.

This is what a lot of the overburden rock looks like that was used to make the rock road.

The Rock Road is more than a woodland path. Built from blasted rock and engineered to endure oxen, horses, and wagons piled high with limestone, it is a raised stone causeway that skirts Lily Pond, crosses wetlands, and still shapes local hydrology. If that road could talk, it would tell of an era when quarries powered the economy and working there cost many lives.

Even just building it required many days of swinging axes, prying stumps, and laying fill through marshes, all while teams of horses and oxen strained against sledges loaded with gravel. In many cases, the quarries were excavated on either side of the road after it was built, and standing water can be observed on the upland side throughout much of the corridor.

Once the quarries opened, the road became a lifeline for an unforgiving trade: limestone blocks split by hand-drilled holes and iron wedges, heaved upright with wooden derricks, and muscled onto wagons one block at a time. Horses pulled the faster loads; oxen hauled the heaviest.

Drivers recounted stories of animals slipping on wet stone, wheels shearing off, and ropes snapping. Every yard of the road was earned — knuckles split, shoulders ruined, teams pushed to their limit. Despite the hardships, the Rock Road carried thousands of tons of stone to the Rockport kilns and wharves, becoming the backbone of a local industry built on sweat, skill, and risk.

A view of the Rock Road section crossing the former Carleton Estate looking toward Lily Pond.

A view of the Rock Road section crossing the former Carleton Estate looking toward Lily Pond.

Anyone holding one of the quarry parcels had the legal right to use the road. That included Young, Fletcher, Thorndike, Emery, Thurlow, Brown, Jones, Burgess, and their successors. In the 1800s, a commissioners’ partition had the force of a court order. It remained in effect unless it was formally discontinued.

Here is a summarized list of important ownership records. I am not a lawyer, but it sure would be nice if someone would donate their time to help finish what was started. Many of us would be eager to help!

1856 – Commissioners create Rock Road. A court-appointed panel surveyed and legally established Rock Road as a three-rod-wide (≈50 feet), roughly half-mile corridor beginning at land set off to George Emery and running 146 rods, then 20 rods & 20 links, to Lime Rock Street in Rockport Village. They granted the right to use this road “in common” to Young, Emery, Fletcher, Thorndike, Thurlow, Burgess, Brown, Jones, Carleton, and others. This was a court-ordered road layout that remained in effect unless formally discontinued. It never was, as far anyone can tell.

1900 – Rockland–Rockport Lime Company inherits the rights. When local quarries were consolidated, the 1900 deed explicitly referenced “the right of way set off… by Commissioners… recorded in Vol. 94,” carrying the original Rock Road rights into the company’s ownership.

1972 – Lime Company conveys Rock Road rights to the Town of Rockport. The Lime Company deed conveyed “all grantor’s interest in the road… and the continuation thereof… to the town road leading to Rockport Village,” transferring all Rock Road rights to the Town.

1994 – Rockport transfers the land (and Rock Road rights) to Mid-Coast Solid Waste Corporation. When Rockport conveyed the transfer-station property to MCSWC, all appurtenant rights — including Rock Road — followed the land because no rights were reserved. MCSWC therefore inherited the entire Rock Road corridor.

1999 – Rockport Select Board votes to clarify rights surrounding Jacobs Quarry trail/Rock Road corridor. Selectmen allocated up to $5,000 to clarify questions and described the route as a “well-used walking path” they wanted the public to continue crossing.

2001 – MCSWC releases Rock Road back to Rockport. In a recorded Release Deed, MCSWC reconveyed “the entire length and width of ‘Rock Road’…” to the Town and reaffirmed that it was the same road described in the 1856 commissioners’ partition, “subject to… the partition dated October 14, 1856… Vol. 94, Page 319.”

Jacobs Quarry showing men working with horses and oxen. The same that would have traveled down the Rock Road to Rockport Harbor. Courtesy Camden-Rockport Historical Society

Jacobs Quarry showing men working with horses and oxen. The same that would have traveled down the Rock Road to Rockport Harbor. Courtesy Camden-Rockport Historical Society

The Dump Connection

Another section of the trail and quarry road extends behind what is now the MCSWC construction debris landfill along the edge of a wooded area where mature trees are interwoven with evidence of test quarries and abundant wildlife. Along the edge of the woods, the road, which is now just a path, turns right and winds its way through wetlands as an elevated causeway and berm before exiting to Linden Lane.

Camden voters approved acquiring this parcel from the Greenfield subdivision for path purposes in 2003 by a wide margin, but it appears the transfer never actually happened. But the road and path have been gently maintained.

Lily Pond, once devastated by pollution from the old Jacobs Quarry dump and surronding development and agriculture, now represents a rare Maine lake restoration success.

In the late 1970s, the DEP documented 50 million gallons per year of leachate flowing toward the pond, triggering algal blooms and oxygen crashes. It took over 25 years of coordinated intervention — partially capping the landfill, diverting groundwater, fencing out cattle, and stabilizing slopes — to restore water quality.

Even today, Lily Pond remains on DEP’s “internal watch list,” considered stable but highly vulnerable.

The Rock Road’s elevated stone berm plays a direct role in that stability, slowing stormwater, filtering sediment, and buffering wetlands. Cutting or disturbing it could accelerate runoff, release sediment, destabilize soils, and send phosphorus to the pond — a risk that could undo decades of progress.

Moreover, low-impact public access is environmental protection. Walkers and bikers serve as informal monitors of the watershed, noticing erosion, culvert blockages, algal blooms, or illegal dumping. Limiting access diminishes this crucial oversight.

Public access to the Mid-Coast Solid Waste and YMCA section of the Jacobs Quarry/Lily Pond trail has gone on for years in a similar way to the Rock Road with which it connects, but these are sites that will need to be monitored for years, long after the landfill is closed.

There’s an opportunity now to recommit to the vision. Historical and educational signage about the quarries, the geology, the lime industry, the ice cutting on Lily Pond, and the environmental challenges and successes that followed would be a community asset worthy of the investment that has already been made.

As Gretchen Piston Ogden wrote in a column some 25 years ago:

“Idealistic? Perhaps. But hey, this area still has a small town countrified feel, and most folks like it that way. It’s still a pleasant place to walk around in and a great place to bicycle, hike, walk, and jog. All I ask is that before you make up your mind how to vote, let your imagination run wild. Imagine your child riding her bike to school or the YMCA. Imagine a Sunday afternoon walk from Camden to Rockport. Better yet try to find the time to stroll the old railroad bed past Lily Pond, site of the proposed Jacobs Quarry Trail.”

Voters overwhelmingly approved what Gretchen was asking them to consider, but neighborhood resistance to paving, rollerblading, and skateboarding halted progress before it even left the planning stage. Perhaps it was the right move not to move forward then.

None of the same people from 1999 are property owners there today, which really does show the importance of taking the long view on a community vision and thinking beyond our own tenancy, but I do value the idea of honoring the Rock Road the way it was built. It’s already there. It’s already resilient. It already tells a story and honors a history that generations of people have worked on.

Moving limestone in Jacobs Quarry

Moving limestone in Jacobs Quarry

Whether through a formal effort to re-establish rights to the shared common way or by the community coming together with landowners to create something we can all be proud of, let’s not let the moment pass us by again.

The Camden-Rockport Pathways Committee works on connecting destinations between our two towns so that people can travel safely by means other than cars. They’ve succeeded in shepherding the pathway/sidewalk on Union Street leading to the YMCA, the sidewalks to Shirttail on Route 105 in Camden, as well as the extension to Hannaford on Route 1 and multiple sections of the Megunticook Riverwalk, which I once considered a total waste of energy.

The people have changed over the years, but the vision has almost always been right.

They are continuing to work on the very long standing goal of providing safe biking and walking to the high school. They deserve our support and advocacy. You can read a recent report on the planning efforts here.

Loading lime onto ships in Rockport Harbor. Photo courtesy Camden Rockport Historical Society

Loading lime onto ships in Rockport Harbor. Photo courtesy Camden Rockport Historical Society

Lily Pond used to be a favorite location for large community skating events and other winter activities. Courtesy CRHS

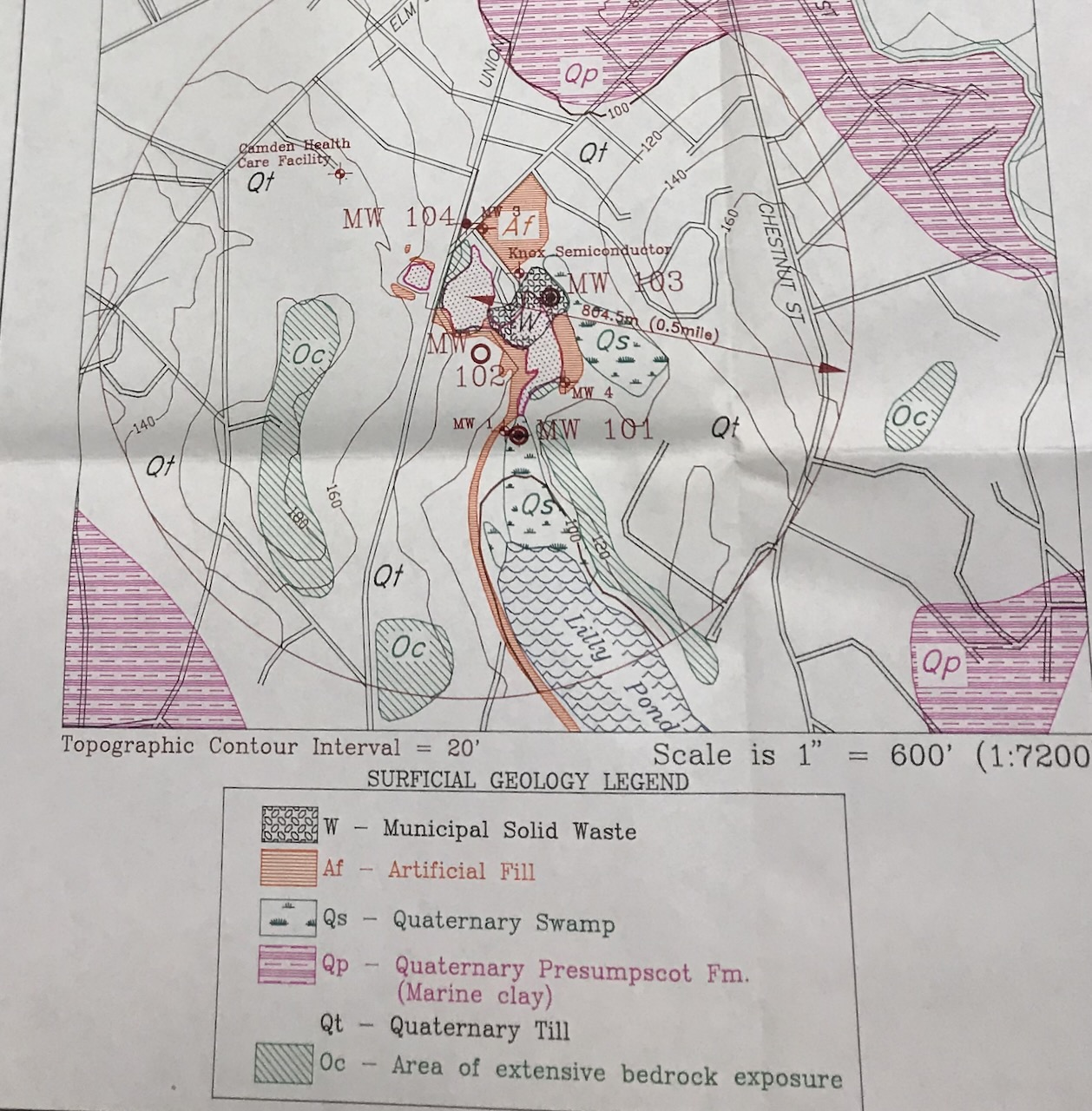

Lily Pond used to be a favorite location for large community skating events and other winter activities. Courtesy CRHS One of the many reports commissioned by the MCSWC board to understand the geology and hydrology of the quarries so that we can keep from polluting Lily Pond.

One of the many reports commissioned by the MCSWC board to understand the geology and hydrology of the quarries so that we can keep from polluting Lily Pond. What the Rock Road is made of. Diagram showing the bands of limestone and marble that the area became famous for.

What the Rock Road is made of. Diagram showing the bands of limestone and marble that the area became famous for.

A diagram used as part of the planning to prevent the contamination of Lily Pond.

Alison McKellar lives in Camden and is a member of the Camden Select Board.