Mark Fourre: ‘We’ve been here before,’ Part I

Pen Bay Medical Center, Waldo County General Hospital CEO Mark Fourre sent the following May 4: As I witness the selfless commitments so many in our communities are making in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, I am reminded how we have responded to past pandemics.

This is not the first pandemic to touch Midcoast Maine. The Spanish Flu of 1918-1920 resulted in between 50 million and 100 million deaths globally, including 5,000 deaths in Maine. How Belfast responded to the Spanish flu offers an interesting window through which to examine today’s COVID-19 experience.

From September 1918 to May 1919, there were 47,000 cases of Spanish flu reported in Maine and 5,000 deaths. During this time, Belfast suffered 35 deaths from influenza and related complications. The mounting death toll was enough to prompt city leaders to act aggressively. From a report by Dr. Orris S. Vickery, secretary to the Board of Health, in the City of Belfast Annual Report 1918-1919:

“The influenza epidemic, prevalent during the autumn months, was so severe in other parts of the state, that after a conference with our Mayor it was deemed advisable to call a meeting of a number of the business men of the city, to consider the question of closing indefinitely the schools, churches and public places of amusements, as the Board did not wish to assume the entire responsibility. It was the unanimous opinion, at this meeting, that such a procedure would be proper under the existing conditions, and those places were closed for approximately three weeks.”

What interests me about this passage is how it demonstrates the willingness of so many local people to embrace the difficulties of daily life to make sacrifices and endure hardships for the greater good.

Of course, like today, not everybody in 1918-1919 was on board with the actions the scientific and medical communities deemed necessary, as evidenced in this passage in the same report:

“It has been very difficult, many times, to make some understand that by obeying the health laws, it was a duty which they as individuals owed to the community.... I refer to the many cases in which it was necessary for the Board to enforce the quarantine regulations.”

Although this passage refers specifically to a Scarlet Fever outbreak in 1918, it is reasonable to imagine that it extended to quarantine regulations related to the Spanish flu.

My first experience with pandemics occurred in the 1980s while I was completing my medical training at the University of California San Francisco emergency medicine residency program at Fresno.

A mysterious illness that came to be known as AIDS had emerged, and it was killing all who became infected. Moreover, it appeared to be a virus transmitted from one person to another through the exchange of blood, including through an errant needle stick or by exchange of bodily fluids. I had experienced needle stick injuries while working with patients as had my fellow residents and medical students.

Many of the patients we worked with were transient, which meant we were not going to be able to track and monitor them, and so we couldn’t reliably assess the risk of our own needle stick injuries. Instead, and this happened to me on more than one occasion, we would have our blood drawn immediately afterward to establish a baseline. Then we would have a series of blood draws over the following weeks to see if there were any changes. During this time, you were presumed contagious, which affected your relationship with your family.

And of course we had to battle our own knowledge that a positive result would be a death sentence. It would be fair to say we were all scared.

But we and the rest of the medical community adapted. Wearing gloves, once an exception, became the norm. Researchers developed therapies to extend the lives of those infected with HIV and continue to search for a cure and a vaccine. And the world adapted, thanks in large part to the educational efforts of governments, academic research centers and non-profits.

And yet, despite all that work, HIV/AIDS persists today. As recently as 2018, 40 years after the pandemic started, more than 1.7 million people contracted HIV and more than 700,000 people died of AIDS-related illnesses.

Overall, more than 74.9 million people have become infected with HIV and more than 32 million have died from AIDS-related illness since the pandemic began.

I bring this up in an attempt to put our current pandemic in perspective.

On one hand you had the devastation of the Spanish flu, which lasted less than two years but infected one third of the world’s population and killed by some estimates as many as 100 million people. On the other hand, you have a 40-year-old pandemic in HIV/AIDS, which continues to claim hundreds of thousands of lives each year and yet gets very little attention.

During each of these pandemics, unemployment, social isolation and the daily tracking of the death toll made life almost unbearably difficult for many people, just as COVID-19 threatens to do now. And yet those before us adapted and eventually overcame their circumstances. They adopted new social norms long before the already outdated elbow bump, and they invested in medical research. COVID-19 may be different from the Spanish flu and HIV/AIDS; but those who endured earlier pandemics can show us the way forward – and give us hope. More on that to come.

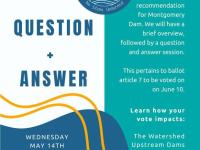

Event Date

Address

United States