Camden-Rockport Historical Society preserves historic quilt collection, launches textile exhibit

Whole cloth Lindsey-Woolsey quilt c. 1700s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

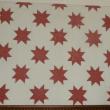

Whole cloth Lindsey-Woolsey quilt c. 1700s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt, 1790-1800s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt, 1790-1800s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Olive green quilt, circa 1790 (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Olive green quilt, circa 1790 (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) President’s Wreath Appliqué quilt, 1850s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

President’s Wreath Appliqué quilt, 1850s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Sawtooth quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

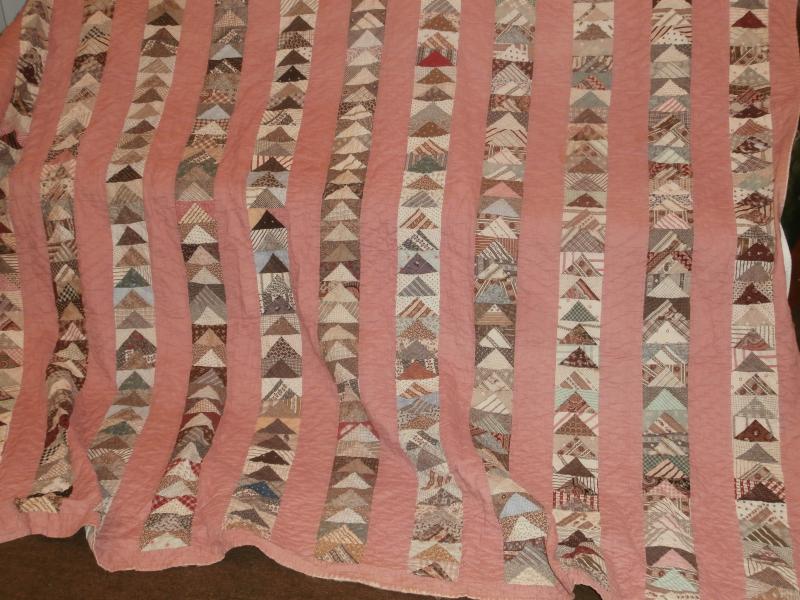

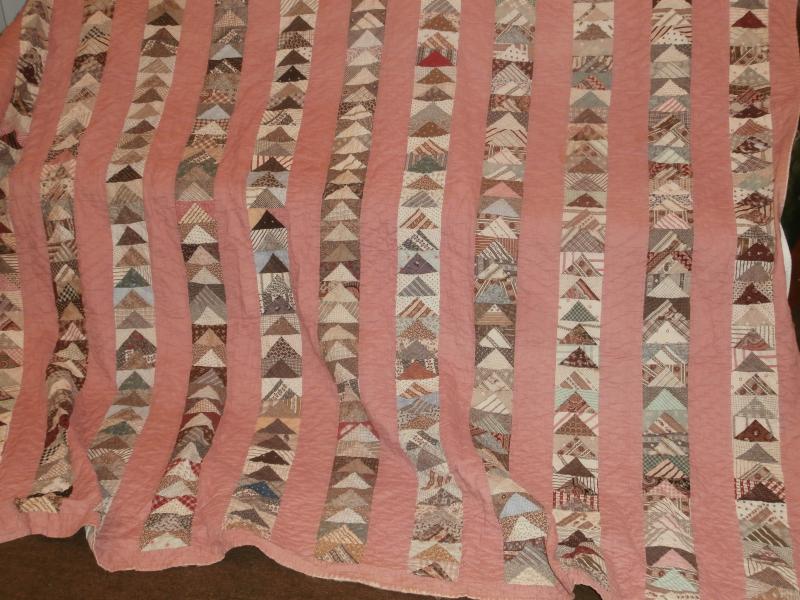

Sawtooth quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Flying geese quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Flying geese quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Whole cloth Lindsey-Woolsey quilt c. 1700s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Whole cloth Lindsey-Woolsey quilt c. 1700s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt, 1790-1800s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt, 1790-1800s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Olive green quilt, circa 1790 (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Olive green quilt, circa 1790 (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) President’s Wreath Appliqué quilt, 1850s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

President’s Wreath Appliqué quilt, 1850s (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Sawtooth quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Sawtooth quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey) Flying geese quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)

Flying geese quilt (Photo courtesy Janet Kelsey)The quilt collection of the Camden-Rockport Historical Society is housed at the Cramer Museum, off of Route 1 in Rockport. There, antique quilts from the 1700s through the mid-1900s are lovingly preserved, each with their own unique story.

The quilts have, for the most part, been donated by local residents and/or relatives of those who owned or made the quilts. Not all the quilts in the collection have a complete provenance but many of the quilts were locally made and figure into local history and lore. As near as possible, the quilts will be presented in chronological order.

A “quilt” is differentiated from other coverlets, comforters or bedspreads in that it is a “sandwich” of two layers of fabric with a layer of batting in between.

The word ‘quilt’ comes from the Latin ‘culcita’ meaning bed. The three layers are then”quilted” or stitched together with rows of stitches or stitching that may or not form fancy designs.

The concept and craft dates back to the Middle Ages and was seen in Europe, India and the Far East.

Quilted vests were worn under armor. Early batting was made from wool. Later batting was made from cotton and was often full of seeds until it was learned how to comb and clean it. Batting serves as an aid in dating quilts by its content and cleanliness.

Sometimes an old tattered quilt would be used (recycled) by placing it between a new layer of fabric and a pieced top.

Early quilting was done by hand. Women would host “quilting bees” in their homes and several generations of women would all work together around a frame to get the quilt done. Once women became proficient with the sewing machine (introduced in the mid 1800s) they experimented with machine quilting but this did not become common until the late 1900s.

Large quilts were difficult to handle on the domestic machine, however, so the turn of the 21st Century found enterprising quilters hiring “Long Arm” quilters to finish their quilts for them.

Whole cloth Lindsey-Woolsey quilt c. 1700s

The earliest specimen of a quilt held by the Historical Society is a remnant of an early “whole cloth Lindsey Woolsey” quilt.

The fabric for a quilt of this type was first woven on a large loom with the weft or horizontal thread being wool (which had previously been spun on a spinning wheel!) and the warp or vertical threads being linen or flax which, like wheat, was first grown and then threshed or beaten down to the base fiber.

Once the “whole cloth” was completed and taken off the loom, it could then be made into a quilt, a time consuming process in and of itself. Sometimes the loom was not wide enough for a full bed and two or three pieces had to be made and sewn together to make the “whole”. But it is still to be differentiated from the later style of patchwork quilts.

This remnant shows how heavy and scratchy the early quilts were but that was all that the early settlers had to work with for textiles; fine broadcloth was not yet available. However, since a fireplace in a drafty, uninsulated cottage was the only heat source, these heavy scratchy quilts were necessary to keep warm!

The dark blue side of this remnant shows the lovely intricate quilting pattern, not easily sewn in such heavy cloth. The brown side clearly shows the warp and weft of the woven textile. The rest of the quilt was probably cut away because of stains or insect damage. Nevertheless, the remnant is a treasure for its example of very early textiles.

Wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt, 1790-1800s

The second of the oldest quilts in the Camden-Rockport Historical Society’s collection is a wool Sawtooth Star patchwork quilt.

Like the first quilt described, the textile is made from woven linen and wool. Textiles were then hand dyed using vegetable or plant dyes. Unlike the first “whole cloth quilt” this one has solid squares alternating with the “Sawtooth Star” square, an early patchwork pattern.

The batting is wool as is the backing. It has a wool binding which is unusual for this 1790-1800s quilt. Quilts of that era were usually finished with a “knife edge” (sewn together and then turned right side out like a pillow case) It is quilted with the early, traditional, “clamshell” pattern.

Olive green quilt, circa 1790

The third of our oldest wool quilts, circa 1790, is a cut down from its original full size probably due to extreme wear or insect damage. It is olive green on the top with a wool batting and backing. The green color was likely “double dyed” first with blue and then with butternut.

The 90 degree cut out lower corners with a 24-inch overhang indicate that it was made for a four-poster bed, which is the hallmark of a New England quilt. The hand quilting stitches are straight rows with connecting lines much like railroad tracks. The quilting was likely done by candle light or whale oil lamp.

President’s Wreath Appliqué quilt, 1850s

Around the end of the 1700s, flax, which was processed into thread or yarn, was no longer grown.

Imports improved and cotton was imported from England, Egypt and India. By the 1850s quilts were becoming more refined and were no longer scratchy Lindsey-Woolsey or “wholecloth” as described in the previous segment.

Quilts began to be pieced or intricately appliquéd as in the fancy Baltimore Album quilts typical in the Mid-Atlantic to Southern states. This 1850s “President’s Wreath” quilt is an early example of appliqué with green and red flowers on a cream background. While this was a popular pattern up and down the Eastern Seaboard, preceding the ever popular Baltimore Album quilts, which, unfortunately, we do not have in our collection.

Our quilt has the cut out corners for the four-poster bed. This is a style which is typical of New England. This quilt was donated by Dorothy Dunton, of Northeast Harbor.

Later, as cotton was being grown in the south, it was shipped to England for milling into cloth which was then imported back to the United States.

Down south on the plantations, the women were wealthy enough to be able to afford to buy fabric imported from England. In the rest of the country, frugality was the rule and quilts were made from scraps of cloth or repurposed clothing that was worn out. Imported fabrics, if they could be afforded at all, was used for new frocks for the ladies or suits for the men. When the clothing wore out, scraps were then pieced into quilts. Nothing was thrown away.

As cotton was increasingly being grown in the South, slaves were brought over from Africa for the picking. Cotton shipped to England for processing into fabric and then exported back to the colonies was expensive and only well-to-do families could afford to buy the textiles. This began to change around 1790 when Samuel Slater was able to set up a mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, solely from memory of the mills in England. This was the very beginning of industry in America and was timed just right for the invention of the Cotton Gin by Eli Whitney in 1793.

The slave trade unfortunately was stepped up as a result of the demand for more and more cotton. Although the quality of the cotton was not as good, this early manufacturing allowed more and more households to be able to purchase a variety of prints and to begin to make clothing as well as the new “American” style patchwork quilt which was typically large blocks and simple patterns.

Women began to invent patterns, often based on household items, natural events or familiar themes like the Monkey Wrench or Churn Dash (butter maker), a simple 4 patch or 9 patch, many different styles of stars, Flying Geese, Jacob’s Ladder, Split Rail Fence, Drunkard’s Path, Oak Leaf, Bear Paw to name a few. Many patterns were regional and some acquired several different names when they were shared across the country

One exception to this new industry was that the Quaker women who, being opposed to slavery, refused to make quilts out of cotton. At that time, their pre-Civil War quilts were made of wool, or silk.

New England was well situated to become a leader in the textile industry because of its many rivers providing power and its’ numerous ports for shipping. Lowell, Mass. is one such city known for its textile mill industry. Many a young woman left the family homestead in Maine and lived in boarding houses in Lowell in order to work in the mills to help support their families.

Flying Geese c. 1825-1850

This pattern was popularized in the second quarter of the 19th Century and is still popular today. It consists of triangles on a contrasting background all heading in the same direction; hence, the name.

The rows of “geese” were typically separated by borders of solid materials. This quilt is hand-pieced and hand-quilted and is in good condition.

It appears to be a “scrap bag quilt” (as most were in their day) as some of the triangle units do not have the adequate contrast that the others had, indicating that the quilter may have run out of that fabric. Today’s quilters enjoy fast piecing methods for many of the older patterns, including Flying Geese, and they are often set into more complex patterns and even now appearing in curves rather than straight rows.

Red Sawtooth Star, 1850-1875

This quilt is pieced using a red discharge print on a white background. It is dated in the third quarter of the1800s, or 1850-1875.

It was hand-quilted, about eight stitches per inch, which was considered fairly crude and unskilled; the highly skilled quilters being able to make about 20 stitches per inch! It has a cotton batting and backing and is finished with a “knife edge” rather than with binding.

This quilt was donated by Marion Moon of Camden.