Bullying, and Maine’s liquor business

Bullying gets a great deal of discussion revolving around social media and school kids. Bullies grow up, however, and a pattern of successful bullying without reprisal in youth leads to the same behavior in adulthood.

The hard liquor business in Maine is run a lot like a bully running rough-shod over every retail establishment that sells hard liquor. Cost, sales price, what can be bought and from whom, (only them), how an order is placed, and even how a retailer pays for purchases is all controlled by a monopolistic system. The monopoly, in turn, is backed by law enforcement paid for by Maine citizens through funding the Maine Bureau of Alcoholic Beverages and Lottery Operations (BABLO).

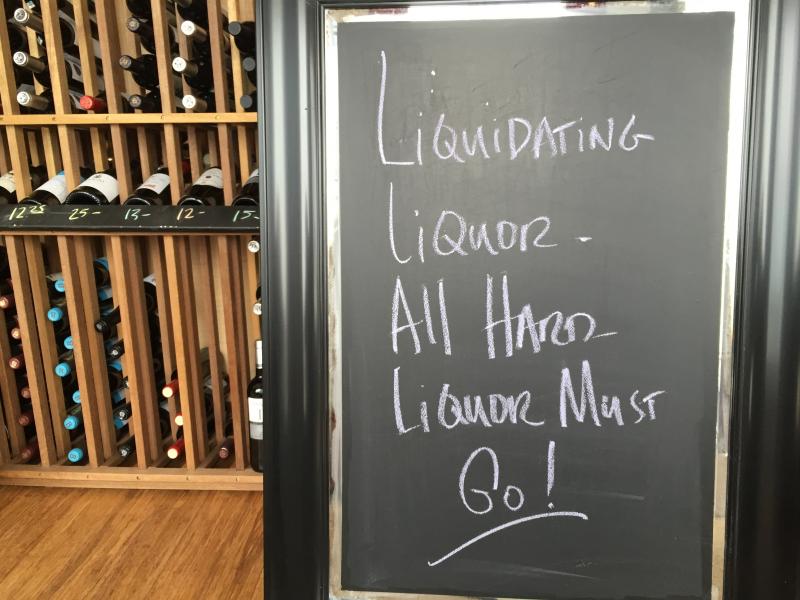

In light of these restrictive rules and policies, as well as extraordinarily minuscule profit margins, RAYR will cease selling hard liquor as of May 4. We will continue to sell beer and wine, for, unlike the hard liquor and spirits business in Maine, beer and wine sales operate under a free market system.

We have made the business decision to part ways with the state and its hard liquor monopoly.

Little known to those outside the sale of hard liquor in Maine is that last year's change in distributor for spirits lead to a change in the way a retailer could pay for liquor purchases. A new requirement was demanded (and strong armed). All retail establishments wishing to continue to sell hard liquor in Maine could no longer pay via check or cash and were forced to pay via electronic funds transfer (EFT).

The only acceptable form of payment was to give the monopoly EFT access to our bank account.

If we did not agree to this, our license to sell spirits and hard liquor would be revoked. Compliance was assured through a series of dunning letters and emails from state liquor law enforcement under BABLO. For retailers like us who balked at the idea of allowing access to their bank account and held out, phone calls were received, followed by in-person visits demanding access, under the threat of losing our license. It was bullying.

To keep our license, we acquiesced and granted EFT ability to our account. Shortly thereafter, however, an unauthorized draft was made on our account for an approximately $850 bottle of liquor that was not delivered. Nearly two months later, after numerous arguments and extensive discussions with BABLO, the situation was finally resolved, but the funds were never actually refunded; rather they were applied as a credit against a subsequent order.

Eight months later, despite assurances from BABLO that this would never occur again, we had the exact same scenario occur again.

Despite the “system” requiring signature of delivery, our account was again debited. Luckily the amount was small and not crippling. When asked for a refund, I was told that the monopoly is “the state” in this situation, and that no reversal of the debit was allowed, according to BABLO.

The “state” does not allow access to its accounts, we were told.

How refunding an illegal debit provides a retailer access to “the state” bank account is a mystery. Even if our money was taken incorrectly, we cannot get a reversal of the debit.

According to BABLO, if you want your money back, order more. To collect the ill-gotten money, the retailer must place yet another order for spirits and alcohol to offset the illegal draft, all enforced by BABLO.

Bully tactics allow large businesses to flourish, but the small retailer, without any level of recourse or law enforcement assistance, cannot adequately function and survive.

A large, irreversible debit to a small retailer’s bank account, especially in the wrong time of year, could actually end a business in Maine. It is that simple.

The business model itself is hard enough to allow survival of small retailers. The margins in the hard liquor business in Maine benefit the monopoly, not the small retailer.

The sale of hard liquor in Maine is an excruciatingly low-margin, high volume, big business — all in a state steeped in pride of small and local. The two are incongruent.

The unsustainable low profit margins insure the business goes to big box stores, which can further high-volume sales. The only way to make hard liquor work in Maine is through high volume. And the EFT payment requirement, legally questionable at best, allows access to bank accounts that should be clearly off limits to a large monopoly with interests in furthering high volume sales to big box retailers.

People, whether tourists or transplants, come to Maine for its beauty, small-town charm and its uniqueness in a sea of homogenization that pervades the U.S. They certainly don’t drive up I-95 to marvel at the tree-barren asphalt parking lots of big box retailers. They come to escape. We need tourist dollars as part of a robust economy. And we need small retailers to continue to survive to provide a unique aspect of community. We don’t need a monopolistic system dictating the future of small retail establishments, especially through an agency of our own state government.

As far as hard liquor is concerned, in the absence of significant change in hard liquor distribution in Maine, the vast majority of the business will reside with national and regional chain and big box stores. As for the more unique, high-end spirits and hard liquor, I strongly suspect bottles of hard liquor will be toted up I-95 to Maine and local retail revenue, as well as, state sales tax, will be forfeited.

Jason Haynes owns RAYR, the wine shop, in Rockport

Event Date

Address

United States