Alison McKellar: On old homes and ancient ecosystems

One of my favorite trees just downstream of the Seabright Dam. It is the largest I have found in the area and overlooks the Megunticook River in its most natural state. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

One of my favorite trees just downstream of the Seabright Dam. It is the largest I have found in the area and overlooks the Megunticook River in its most natural state. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

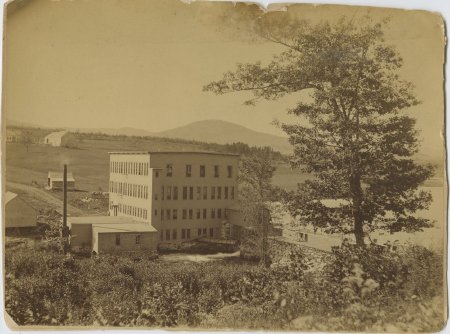

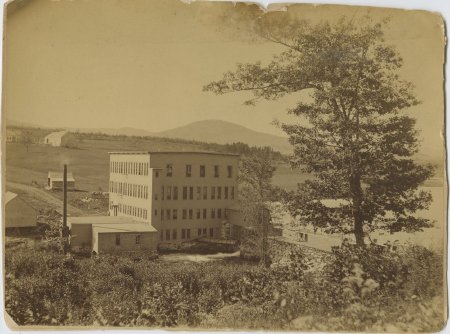

Seabright Dam historic photo: this photo shows the same area around the Seabright Dam in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Quite evident is the extent of the clearing done in the century before. The larger tree may be one of the trees visible today. (pPhoto courtesy of the Walsh History Center)

Seabright Dam historic photo: this photo shows the same area around the Seabright Dam in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Quite evident is the extent of the clearing done in the century before. The larger tree may be one of the trees visible today. (pPhoto courtesy of the Walsh History Center)

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

Another view of the Sea Street Ash Tree. This tree would have already been mature when the first settlers arrived in 1768 and is one of the few that was preserved. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

Another view of the Sea Street Ash Tree. This tree would have already been mature when the first settlers arrived in 1768 and is one of the few that was preserved. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

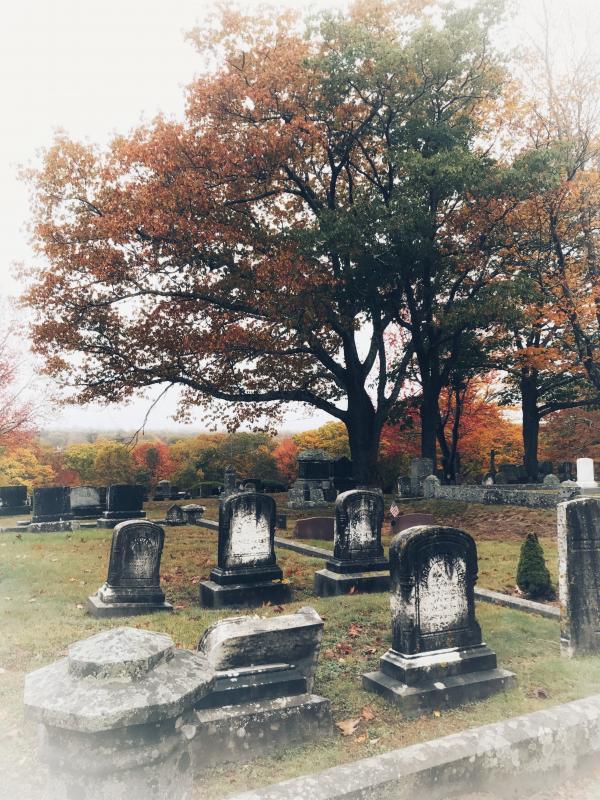

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th Century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th Century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

My home on Mechanic St in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of the Walsh History Center which has two binders full of photos of every house in Camden, taken as part of a Depression era project.

My home on Mechanic St in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of the Walsh History Center which has two binders full of photos of every house in Camden, taken as part of a Depression era project.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

One of my favorite trees just downstream of the Seabright Dam. It is the largest I have found in the area and overlooks the Megunticook River in its most natural state. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

One of my favorite trees just downstream of the Seabright Dam. It is the largest I have found in the area and overlooks the Megunticook River in its most natural state. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

Seabright Dam historic photo: this photo shows the same area around the Seabright Dam in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Quite evident is the extent of the clearing done in the century before. The larger tree may be one of the trees visible today. (pPhoto courtesy of the Walsh History Center)

Seabright Dam historic photo: this photo shows the same area around the Seabright Dam in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Quite evident is the extent of the clearing done in the century before. The larger tree may be one of the trees visible today. (pPhoto courtesy of the Walsh History Center)

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

Another view of the Sea Street Ash Tree. This tree would have already been mature when the first settlers arrived in 1768 and is one of the few that was preserved. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

Another view of the Sea Street Ash Tree. This tree would have already been mature when the first settlers arrived in 1768 and is one of the few that was preserved. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th Century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

The trees at the Mountain View Cemetery are a living testament to the evolving relationship between humans and nature and they all have a certain magical quality. This one was likely planted in the late 18th or early 19th Century. (Photo courtesy Alison McKellar)

My home on Mechanic St in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of the Walsh History Center which has two binders full of photos of every house in Camden, taken as part of a Depression era project.

My home on Mechanic St in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of the Walsh History Center which has two binders full of photos of every house in Camden, taken as part of a Depression era project.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

This giant Ash tree on Sea Street is said to be the oldest in Camden at around 300 years. It straddles the fence between two property owners who have made its health a preservation a priority.

The older homes of Camden were built from the virgin forests that drew British ships and the first settlers into this little harbor called Negunticook.

The homes may date back a century or two, but contained within them are the secrets of all the centuries that came before. The trees that built our old homes grew from the soil that had never been touched, rich in the nutrients transported by abundant wildlife, the sea that had once covered it, and the rocks and minerals crushed into sediment by the glaciers as they receded.

These perfectly aged trees weathered the storms of 100 years, and still they grew, slowly, patiently, and wisely as they carefully adapted to the unique dance of nature in Midcoast Maine. Here in our little haven, where the mountains meet the sea, these old buildings have stood the test of time. They too are a part of the ecosystem, a monument to the self reliance and the cherished Maine ethic of making things last.

Most of us are transplants from another land, but not our homes. I often dream of what it must have been like here before the settlers arrived, but development happened quickly in Camden and the clues are sometimes not so obvious.

My old house, though, and many others, are natives with deep roots. They are built from the ancient trees that knew how to live here when the river ran free and the Wawenok Indians gathered in their shade.

Our homes, like the trees that frame them, know how to swell and contract with the seasons, and the salty sea breezes and cycles of freezing and thawing are all familiar to a home made from native forests. The adolescent southern pine that we use to build new homes is ill prepared to stand tall through all the Maine seasons, but an old growth hemlock is undaunted.

Our old lumber remembers when mountain lions and wolves outnumbered people and when the only fish hatcheries we needed for brook trout were the cold, rocky streams at their feet. The trees’ roots grew when they could still suck up nutrients brought in by smelt and alewives each spring from the sea as they raced up the river to spawn.

Today, the fish from the sea are blocked by dams and the trout are grown in labs and hatcheries to be released annually. The only fish that can survive and reproduce on their own are the bass in the lake, and they, too, were transplanted from somewhere else. The water bodies today are not the ones the old trees knew and the soil that the trees grow in does not provide the nutrients it once did.

If you look carefully, you can see the wisdom of an ancient ecosystem in the grain of the wood of Camden’s old homes.

The rings of the trees are close together because the timber grew strong and slow and tough. It does not rot like the new, fast growing wood that was grown in far off places, and harvested before reaching maturity. It was grown for profit, and just as a racehorse who is pushed to his limit before his bones are fully formed, the youthful exuberance of young wood is also subject to decay.

The trees that built these old homes are the same that the early settlers spotted off the coast and were selected to build the ships that sailed the Atlantic. Some of the homes have crooked floors and doorways that swell and contract, and the impatient among us demand a fix and a pace that nature never intended. We want to start fresh and fast, but the old house knows how to bend with time, to change with the seasons.

Most of what we eat, and even the materials we use to build our new houses, are brought in from somewhere else now, and things can be shipped out just as easily.

Dumpsters from out of town companies come in to be loaded up with the old homes carved from our virgin forests, to be replaced with composite siding and engineered wood. Time is money and people want what they want. Not a house from ancient hardwood that was built to last hundreds of years, but a floor plan just like the one they built in Florida. Maybe easier to just start over, they say. Clear the canvas.

Little stands in their way, because in Camden, a town that has nine pages of rules to regulate the placement and size of signage, there are virtually no barriers to the demolition of homes nor requirements for the reuse and recycling of materials.

I wish I had known before I replaced my first wooden window with a vinyl one, that the lumber of the old growth forests of the Camden Hills cannot be easily outdone by the latest chemical infused composite from China, no matter how energy efficient it claims to be in the short term. Sure, those air tight, gas sealed, double paned windows seem like just the modern upgrade at first, but when the first pane breaks or the gasket wears out, you learn quickly that the unit is not designed for repair.

There is no patch or putty solution that will do, and often the whole window has to come out, destined for the landfill to be buried forever with tannery waste, mattresses, and old growth timber from last season’s remodel.

These are the things that a young or transient homeowner does not know. The wood I’ve replaced on my old home probably should have been patched instead, for the new stuff is already showing signs that it won’t last long.

Some old things must inevitably be replaced, and not everything old is worth keeping, but there is a wisdom in nature and local ecosystems that cannot be altered without consequences. The best homes are built with the old, local trees that lives and died here.

The horse hair plaster of my home is sometimes an inconvenience, but it does not emit toxic gasses like Chinese drywall or spray foam insulation, and I do not have to wonder about the environmental degradation happening in the factories and forests where these new materials are being mined and manufactured.

Sometimes, we are so eager to innovate that we forget the great strength and wisdom of what came before us.

Look back in any old newspaper and you will see stories of homes being moved or taken apart in Camden. The people who built Camden’s old homes could still remember the trees that once stood in their place, fortified by the richest soil and the cleanest air that took hundreds if not thousands of years to form.

When a building needed to make way for progress, they did not waste the resources that built it. Taking things apart and moving them out of the way was slower and more arduous then, and so it was done more thoughtfully.

Today, a house can come down with an excavator in a single day, but we should learn from nature and choose to treat our old homes as a community resource that is part of a larger and very special ecosystem.

Alison McKellar lives in Camden and sits on the town’s Select Board.

Event Date

Address

United States