Ari Snider: The French paradox

"The land plunged into the choppy aquamarine surf of the Channel." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The land plunged into the choppy aquamarine surf of the Channel." (Photo by Ari Snider)

I paused to examine a bomb crater. (Photo by Ari Snider)

I paused to examine a bomb crater. (Photo by Ari Snider)

"I practiced the zen exercise of balancing stones in ways that challenge gravity, while André, my host father, practiced the slightly less zen exercise of launching pebbles at my delicate constructions." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"I practiced the zen exercise of balancing stones in ways that challenge gravity, while André, my host father, practiced the slightly less zen exercise of launching pebbles at my delicate constructions." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A classic French chateau." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A classic French chateau." (Photo by Ari Snider)

... And its cozy interior. (Photo by Ari Snider)

... And its cozy interior. (Photo by Ari Snider)

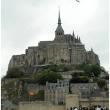

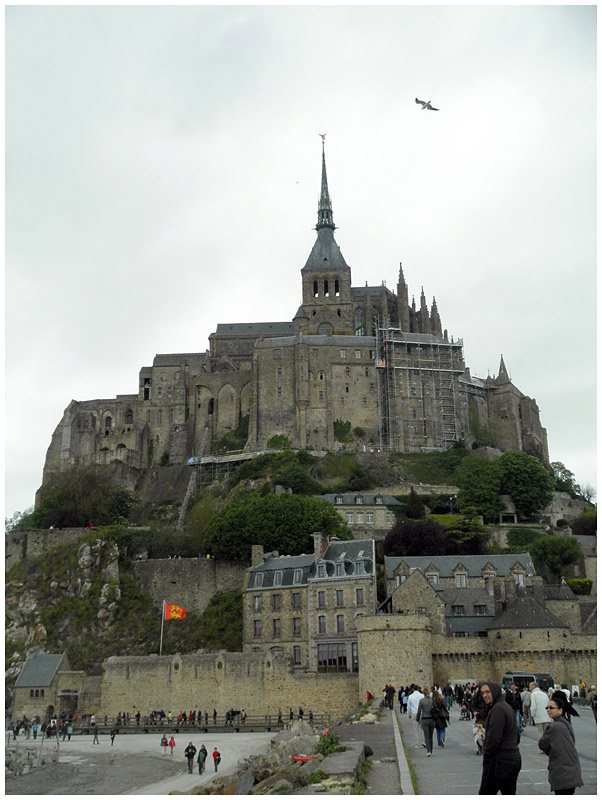

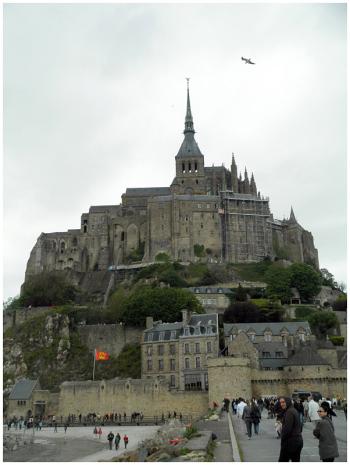

"A colossal Gothic cathedral that dominates the island like a stone dragon guarding its nest." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A colossal Gothic cathedral that dominates the island like a stone dragon guarding its nest." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"An infinite monotone carpet." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"An infinite monotone carpet." (Photo by Ari Snider)

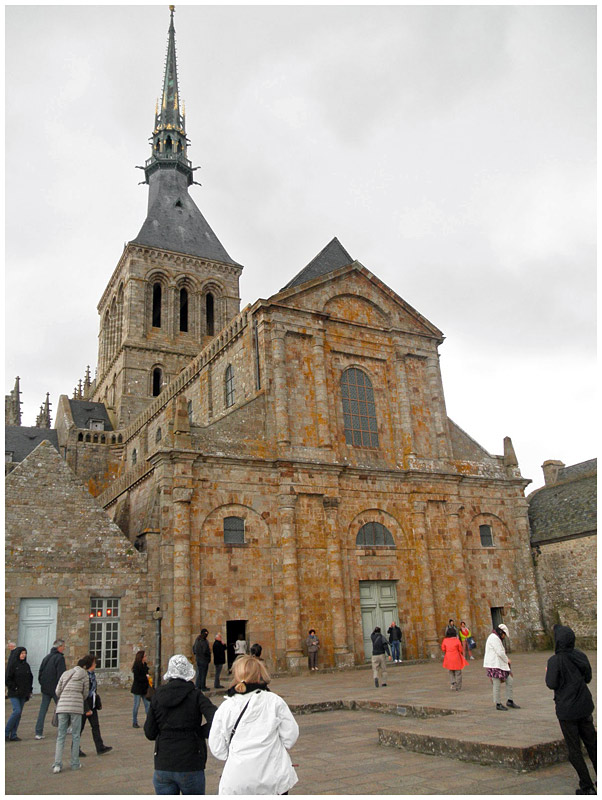

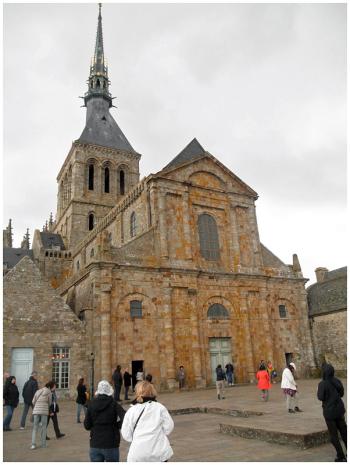

The cathedral itself. (Photo by Ari Snider)

The cathedral itself. (Photo by Ari Snider)

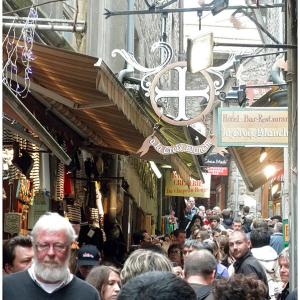

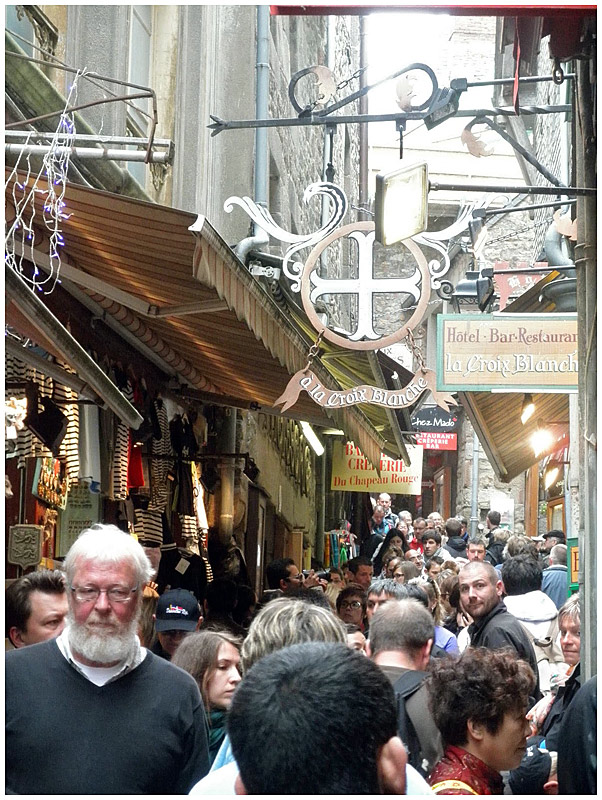

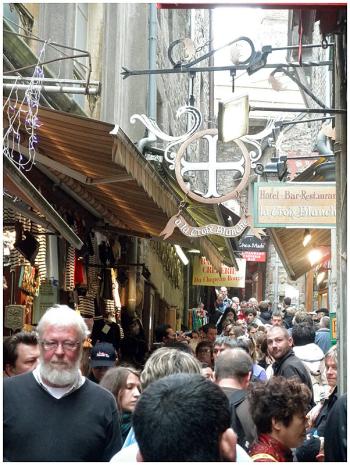

"The 40 or so 'Montois' welcome upwards of 5 million tourists annually." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The 40 or so 'Montois' welcome upwards of 5 million tourists annually." (Photo by Ari Snider)

The French Paradox: Sprawling parking lots and Unesco World Heritage Sites. (Photo by Ari Snider)

The French Paradox: Sprawling parking lots and Unesco World Heritage Sites. (Photo by Ari Snider)

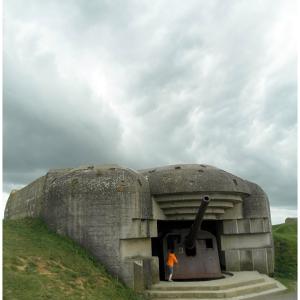

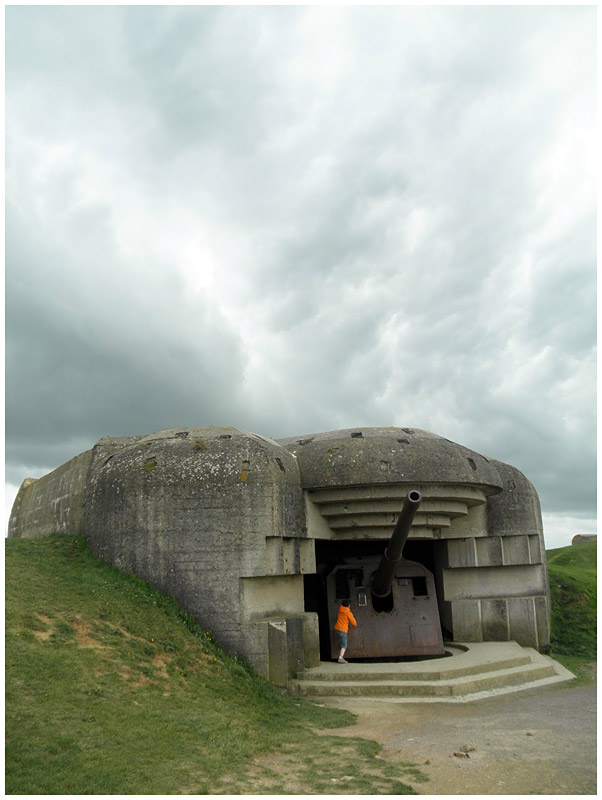

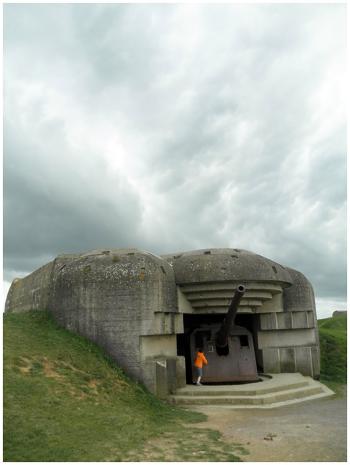

"Several bunkers harbored 150mm anti-aircraft cannon thrusting lazily towards the heavens." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Several bunkers harbored 150mm anti-aircraft cannon thrusting lazily towards the heavens." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Experiencing such a place humanized the War, rendering it all the more horrifying." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Experiencing such a place humanized the War, rendering it all the more horrifying." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The land plunged into the choppy aquamarine surf of the Channel." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The land plunged into the choppy aquamarine surf of the Channel." (Photo by Ari Snider)

I paused to examine a bomb crater. (Photo by Ari Snider)

I paused to examine a bomb crater. (Photo by Ari Snider)

"I practiced the zen exercise of balancing stones in ways that challenge gravity, while André, my host father, practiced the slightly less zen exercise of launching pebbles at my delicate constructions." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"I practiced the zen exercise of balancing stones in ways that challenge gravity, while André, my host father, practiced the slightly less zen exercise of launching pebbles at my delicate constructions." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A classic French chateau." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A classic French chateau." (Photo by Ari Snider)

... And its cozy interior. (Photo by Ari Snider)

... And its cozy interior. (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A colossal Gothic cathedral that dominates the island like a stone dragon guarding its nest." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"A colossal Gothic cathedral that dominates the island like a stone dragon guarding its nest." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"An infinite monotone carpet." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"An infinite monotone carpet." (Photo by Ari Snider)

The cathedral itself. (Photo by Ari Snider)

The cathedral itself. (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The 40 or so 'Montois' welcome upwards of 5 million tourists annually." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"The 40 or so 'Montois' welcome upwards of 5 million tourists annually." (Photo by Ari Snider)

The French Paradox: Sprawling parking lots and Unesco World Heritage Sites. (Photo by Ari Snider)

The French Paradox: Sprawling parking lots and Unesco World Heritage Sites. (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Several bunkers harbored 150mm anti-aircraft cannon thrusting lazily towards the heavens." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Several bunkers harbored 150mm anti-aircraft cannon thrusting lazily towards the heavens." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Experiencing such a place humanized the War, rendering it all the more horrifying." (Photo by Ari Snider)

"Experiencing such a place humanized the War, rendering it all the more horrifying." (Photo by Ari Snider)

NORMANDY, France – Belgium has a complicated relationship with France. On one hand, France offers sunny beaches, snow-capped mountains, picturesque countrysides, and vibrant cities to visit, while at the same time supporting the cultural foundation of the Francophone world. However, most Walloons find the French insufferably haughty. Fortunately, the inn that we had booked for a long-weekend in Normandy was owned by a Belgian couple.

Despite Belgians' mixed feelings towards its southern linguistic cousins, Wallonia's proximity to the French Republic is a definite travel advantage. Several short hours after leaving Brussels, we reached the soaring cliffs that border the English Channel. We parked the car and climbed the rolling hills that cup the charming seaside village of Etretat in a verdurous embrace.

A fierce wind whipped vertically up the limestone bluffs, mitigating the efforts of the sun blazing from a patchy sky. Below us, the land plunged into the choppy aquamarine surf of the Channel. Great Britain hid behind its thick cloak of fog somewhere beyond the horizon.

The trail descended eventually through a narrow crevasse that spilled out onto the beach of smooth stones. The ocean hissed with each wave as it bit into the pebbled beach. I practiced the zen exercise of balancing stones in ways that challenge gravity, while André, my host father, practiced the slightly less zen exercise of launching pebbles at my delicate constructions.

Like its relationship with Belgium, France itself is filled with contrapositions. The most blatant is the disparity between the beauty of France's countryside and the ugliness of its urban sprawl. En route to our inn, the clean autoroute rolled through endless fields where cows chewed their cud lazily in the shadow of ancient oak trees. Then, in the blink of an eye, a soulless spread of department stores, parking lots, and yes, a McDonalds, sprung around us, suffocating the countryside beneath a blanket of asphalt and metal.

Our bed and breakfast, a classic French château, was buried in the countryside not five minutes from this lifeless splotch of suburbia.

The amiable Belgian proprietor greeted us and introduced us to the manor. The Canadian Air Force had used the property as a regional headquarters during the Second World War. The adjacent field had served as a landing strip for several hundred Mustang fighter jets.

Upon learning that I was American, he bid me a sincere "congratulations." The response took me by surprise but also touched me. Being American saddles one with a hefty load of cultural and political baggage. After spending the better part of a year supporting this burden, being congratulated for my nationality filled me with an indescribable comfort.

The next morning we loaded into the minivan for a pilgrimage to Mont St. Michel, perhaps the most famous symbol of French culture after the Eiffel Tower.

Legend has it that in the early 700s, St. Michael came to St. Aubert in a dream and instructed him to build a church. When St. Aubert refused, St. Michael descended anew, this time to burn a hole in poor Aubert's cranium. Needless to say, St. Aubert capitulated, establishing a small monastery on one of the tidal islands that rise like camels' humps from the sand flats of coastal Normandy. Over the course of the intervening centuries, St. Aubert's monastery has grown into a colossal Gothic cathedral that dominates the island like a stone dragon guarding its nest.

Ari Snider is a Belfast Area High School junior studying in Belgium through Rotary International. He currently lives with a host family in Waterloo. His discoveries and adventures abroad have been the subject of his blog Belfast/Belgique

We joined the herds of tourists trailing towards the Mont by way of a paved dike. Mont St. Michel is France's most visited location after Paris, and the 40 or so "Montois" welcome upwards of 5 million visitors annually.

We entered through a grand door in the stone wall that skirts the island, and began the hike towards the cathedral far above. A series of steep stairways and tight stone switchbacks brought us above the clustered shingled roofs and through several quiet parks hatched into the Mont's rocky haunch.

Stern clouds spat rain from a somber sky as we attained the summit. We savored a few moments in the shadow on the stone plaza overlooking the Mont and the surrounding intertidal zone. Below us, a panorama of sand flats that stretched towards the horizon in an infinite monotone carpet. However, a cold and gusty wind obliged us to take refuge in the cathedral.

Unlike the Allied Forces, we approached Omaha beach from the land. The ocean bombarded the cliffs with howling fits of salty breath, and the sky pressed its metallic chest low overhead. The German fortifications contrasted darkly against the innocent fields of green and yellow bowing in the wind.

The bunkers overlooking Omaha Beach are some of the best preserved vestiges of the Nazi fortifications that studded the Atlantic coast during World War II. They now stare vacantly across the Channel throughout slitted eyes. Several still harbored 150mm anti-aircraft cannon thrusting lazily towards the heavens as rust steadily engulfed their pockmarked flanks.

The bunkers seemed all but lifeless, nothing more than soulless concrete shells. All the same, entering bunkers instilled odd feelings in me. There I was, touching the same walls, standing on the same floors, listening to the same ocean as the Nazi soldiers had not so very long ago. Experiencing such a place humanized the War, rendering it all the more horrifying.

Event Date

Address

United States