What are we doing with our CFLs?*

A box of fluorescent tubes at the Belfast Transfer Station among others that will be used to deliver discarded bulbs to Veolia Environmental Services for disposal. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A box of fluorescent tubes at the Belfast Transfer Station among others that will be used to deliver discarded bulbs to Veolia Environmental Services for disposal. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

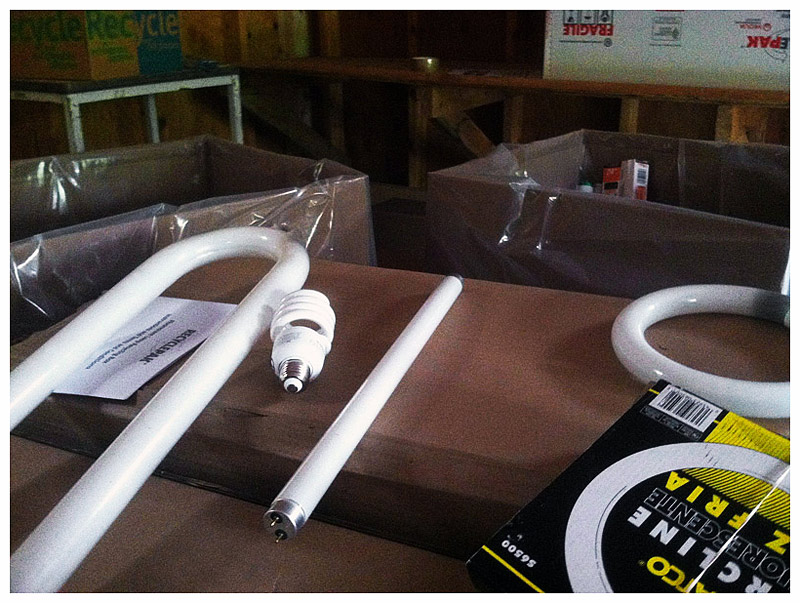

The increase in popularity of screw in compact fluorescent bulbs, center, has brought attention to the mercury content in older style, straight, U-shaped and circular tubes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The increase in popularity of screw in compact fluorescent bulbs, center, has brought attention to the mercury content in older style, straight, U-shaped and circular tubes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Broooks town office volunteer Jimmy Mulcahey looks at packaging provided by Veolia Environmental Services. The town turned to the company last fall to give residents an alternative to bringing fluorescent tubes to the transfer station in Thorndike. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Broooks town office volunteer Jimmy Mulcahey looks at packaging provided by Veolia Environmental Services. The town turned to the company last fall to give residents an alternative to bringing fluorescent tubes to the transfer station in Thorndike. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A box of fluorescent tubes at the Belfast Transfer Station among others that will be used to deliver discarded bulbs to Veolia Environmental Services for disposal. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A box of fluorescent tubes at the Belfast Transfer Station among others that will be used to deliver discarded bulbs to Veolia Environmental Services for disposal. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The increase in popularity of screw in compact fluorescent bulbs, center, has brought attention to the mercury content in older style, straight, U-shaped and circular tubes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The increase in popularity of screw in compact fluorescent bulbs, center, has brought attention to the mercury content in older style, straight, U-shaped and circular tubes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Broooks town office volunteer Jimmy Mulcahey looks at packaging provided by Veolia Environmental Services. The town turned to the company last fall to give residents an alternative to bringing fluorescent tubes to the transfer station in Thorndike. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Broooks town office volunteer Jimmy Mulcahey looks at packaging provided by Veolia Environmental Services. The town turned to the company last fall to give residents an alternative to bringing fluorescent tubes to the transfer station in Thorndike. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

BELFAST - Not long after the tranfer station here dropped its fee for fluorescent bulbs, manager Sandy Carey noticed a trend. The number of people returning bulbs was rising in a predictable word-of-mouth kind of way, but the number bulbs per person was high from the start.

“We’ve had quite a few people come in with bags full of bulbs,” she said. “They’ve been holding onto them because they don’t want to pay.”

Belfast previously charged $1.20 for a 4-foot straight tube and comparable rates for other sizes and styles, including compact fluorescent lamps.

The connundrum with the increasingly popular “green” CFLs and their less-celebrated predecessors, straight fluorescent tubes, is that they contain trace amounts of mercury, an environmental pollutant. The EPA puts fluorescent bulbs in the same “universal waste” category as batteries, pesticides and other mercury-containing equipment. For residents and municipal transfer stations, this means separating the bulbs from the rest of the garbage and figuring out how to get rid of them.

Belfast was able to cut cost out of the equation by teaming up with Veolia Enviromental Services — one of a handful of companies that processes household hazardous waste in New England.

Veolia works with businesses and municipalities to collect and process the bulbs, streamlining the process by providing special packaging for a variety of fluorescent tubes and shipping labels.

“It’s been great,” Carey said. “When it’s ready, we call [FedEx] and it’s gone.”

But where does it go? And how does Veolia dispose of the lamps for free?

According to Paul Conca, operating manager forVeolia ES the bulbs are shipped directly to the company’s new facility in West Bridgewater, Mass. where they are disassembled in a negative pressure enviroment with proper air pollution controls into their constituent parts.

A typical fluorescent bulb would be broken down into aluminum end caps, glass, mercury and phospor powder — the coating that turns the ultraviolet photons generated inside the bulb into visible, white light.

Conca said the end caps are typically recycled. The glass, he said, is used in a landfill near the facility as alternative daily cover, a blanket term for anything other than earth that is used to cover waste on a given day.

Veolia pulls a fairly pure form of mercury from the phospor powder and sells it to companies that further refine it, Conca said. From there it can be sold back into the market for a variety of product, including light bulbs.

Veolia has been recycling fluorescent lamps and a variety of other Universal Waste in New England since 2000. A fairly recent wild card in the process has been the swing in the market for rare earth elements, which are present in the phospor in fluorescent tubes and are critical to the manufacture of a wide range of products from computers, TVs and household electronics to medical equipment and hybrid vehicles.

China has been making headlines recently for trying to corner the market on rare earth elements. The situation is still evolving but could make the elements more valuable in the US.

Conca said concern over rare earth availability has added a new twist to Veolias’ work. But for now, he said, selling the component materials of fluorescent bulbs falls short of the cost of operations. Veolia does more than just fluorescent bulbs and some of the programs are more lucrative than others, he said. The bulb disposal program also receives funding from the National Electrical Manufacturers Association, a trade organization.

Maybe most importantly, fluorescent bulbs aren’t being buried inside a mountain somewhere.

“That’s one of Veolia’s commitments,” Conca said, “to reduce the amount of these materials that without these programs would end up in landfills.”

The response in Belfast suggests that residents are at least somewhat aware of the need to keep CFLs and other fluorescent bulbs out of the dumpsters and garbage bags. Carey said there’s been a slow increase in the number of bulbs of all varieties coming in since the fee was lifted.

Still, she said, there’s more work to do in spreading the word.

“People don’t know,” she said. “A kid said to me, I love smashing those. I love the noise they make. I was like, Oh my God.”

Find a list of free fluorescent bulb drop-off sites, including municipal transfer stations and businesses here.

Ethan Andrews can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States