This Week in Lincolnville: $1,000 Worth of Pennies

The Ames family came by their farm, which sits on the Northport/Lincolnville town line, in 1837 through the negligence of one of Benjamin Carver’s sons.

It seems this son had let the farm deteriorate so badly that his own father put it up for sale. Perhaps the father hadn’t trusted in his son’s husbandry enough to actually deed it over to him, and so kept control.

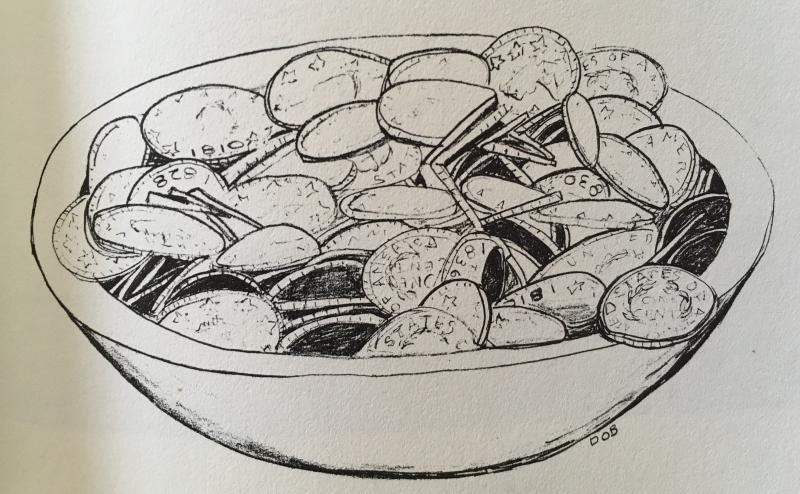

When Isaac Ames offered him $1,000, Benjamin, ever cautious, said he’d only sell it for specie, or coin. But this didn’t stop Isaac, who produced the full amount in pennies. He loaded it into a wheelbarrow, and pushed it up to Benjamin’s place [the old Ulmer house, 3 South Cobbtown Road]. Once there they scooped the pennies into wooden bowls and dumped them on the dining room table to count them. And that’s how Isaac paid for his farm.

These stories from Ducktrap: Chronicles of a Maine Village available at Sleepy Hollow Rag Rugs.

Isabel Ames, great-granddaughter of the sly Isaac Ames, and her brother Robie, spoke of the old place where they grew up. Their memories brought the Ames family homestead alive:

Robie Ames and Mary Drinkwater married in 1905, starting their lives together when they were barely twenty. A year later their first child, Isabel was born, and a year after that, Merton, followed in subsequent years by Robie Jr., Alwilda, and Edwin. The family lived in the Ames homestead on the shore; the Northport town line runs between house and barn.CALENDAR

TUESDAY, Aug. 30

Library open, 3-6 p.m., 208 Main Street

WEDNESDAY, Aug. 31

Library open, 2-5 p.m., 208 Main Street

Planning Board, 7 p.m., Town Office

FRIDAY, Sept. 2

Library open, 9-noon, 208 Main Street

SATURDAY, Sept. 3

Pickleball Beginners Open Play, 8:30-9:30 a.m., Town Courts, LCS

Library open, 9-noon, 208 Main Street

EVERY WEEK

AA meetings, Tuesdays & Fridays at noon, Community Building

Lincolnville Community Library, For information call 706-3896.

Schoolhouse Museum closed for the summer, 789-5987

Bayshore Baptist Church, Sunday School for all ages, 9:30 a.m., Worship Service at 11 a.m., Atlantic Highway

United Christian Church, Worship Service 9:30 a.m., 18 Searsmont Road or via Zoom

COMING UP

Sept. 6: First Day of School

The shore with its ledges and sandy beach was a perfect place to play; Isabel remembers going down there with her little brother Merton, making dishes out of the clay they found and drying them in the sun. Once they walked a long way down the shore, only to look up and find their mother standing over them sternly. She’d been keeping an eye on them all the time. Sometimes Isabel would play dolls with Elizabeth Griffin who stayed summers at her grandmother’s house on the Howe Point Road.

Girls kept close to home, Isabel says, while boys might wander to the Trap or upstream to the shiner hole. When the Ames children were growing up there were only remnants of the old enterprises at the Trap. The dam was broken down with gaps in it and there were only remains of the grist mill and lime kiln.

Though Isabel had a bike and would deliver milk to a family friend at the Trap, she was more likely to be helping her mother at home. “Go wheel the babies” was a familiar order as three younger siblings arrived; pushing them back and forth in the buggy in the dooryard would quiet them.

But helping could also mean bringing something home for dinner, and on occasion the little girl might row out in front of the house and catch a haddock on a line using clams or periwinkles for bait. In a short time it was possible to catch a bushel of haddock. Cod, pollock, cunners, and flounder were all plentiful. Another regular chore was leading the Jersey cows to and from their pasture across the road for the morning and evening milking, a chore Isabel did with Merton.

Their father, Robie, kept a couple of cows, a horse, pigs, and chickens. Mary made butter, which they sold along with their milk and eggs. In a good year the big strawberry patch yielded enough to ship to Boston.

In addition to farming, Robie fished for salmon, setting his weirs off the shore at Knight’s Point, north of their shore. The salmon were packed in ice and shipped to Boston on the steamboat, or sold locally if possible. The family tasted salmon only on the Fourth of July, or when a customer wanted just part of a fish, they’d eat the rest.

Mary canned all the garden produce, and made hogshead cheese and sweet-pickle meat when the pigs were slaughtered. Preserved meats and vegetables were stored in the root cellar. Isabel remembers going down cellar for a piece of the sweet pickle meat to be fried in lard for supper.

Her mother also put down surplus eggs in water glass, a preservative which kept them useable for several months; the eggs could only be used in baking though, not as fresh eggs. Butter too was “laid down” for winter use. Mary picked buckets of blueberries on Ducktrap Mountain to can and sell, and made sauce with the fruit of her two pear trees.

Nothing was thrown out unless every possible use had beeb made of it. Robie Jr. remembers their mother breaking up the clam shells from clam dinners on the well curbing. The crushed shells were fed to the hens as a source of calcium to strengthen their egg shells.

Sawdust from cutting up the winter’s firewood was saved for the ice house; ice cut on their farm pond in winter was thus packed in insulating sawdust and kept for shipping salmon in early summer.

And livers from the codfish were placed in a pan of water in the sun; in a few days a layer of codliver oil would form on top of the water. This oil was collected to sprinkle over the shallows where flounder lay on the bottom, “smoothing” the water so the fish could be seen clearly to spear. Another use of the fish oil was to grease the slips used to launch the wherries.

In 1962 Robie Sr. sold his fishing gear, including his fish house and wherry, to the Mystic Seaport Museum. Isabel wrote down, at that time, her recollections of the salmon fishery:

“Salmon fishing was being carried on in Penobscot Bay by 1837, perhaps before, as early in that year Isaac Ames came to Northport, bought the property still occupied by his descendants, and engaged in fishing for salmon.

“His son, George Ames, continued fishing at the same location, considered the major salmon fishing area along the coast. All the properties along the coast from Camden to Searsort had so-called salmon berths fished by the property owner or leased to other fishermen.

“In this area the largest catch in any one day by an individual is thought to be 52 salmon caught by George Ames in one season between 1880 and 1885. The salmon catch varied greatly from year to year, there being cycles of good and bad years.

“After fishing with his father George, Robie Ames Sr. fished alone from 1903 to 1947. In 1933 he bought out the fishing gear of the only remaining fisherman in the area, a Mr. Griffin, and so became the last of the salmon fishermen in Penobscot Bay.

“The daily accounts of Robie Ames show his largest catch to have been 49 salmon on July 13, 1936. From 1939 on there was a steady decline in the number of fish taken. In that year he took 36 salmon, in 1940 only 17, and in 1947 only 4. That was the last year of salmon fishing in Penobscot Bay as Robie retired with the end of the salmon season.”

The Ames children attended school at Saturday Cove in Northport, since they actually lived in that town, though Isabel attended a few terms at the Beach School in Lincolnville. Ducktrap’s schoolhouse was long gone by then.

But going to high school meant a real commitment for country families. Isabel’s mother thought her too young to begin high school in the fall after eighth grade, so she stayed at Saturday Cove where the teacher saw to it that she had algebra and oral themes and bookkeeping – high school courses, so she wouldn’t be too far behind. Then part way through the year, the Superintendent of Schools told Mary Ames that her daughter was wasting her time and ought to be in high school.

So in March she entered Camden High School as a freshman. Thanks to her extra preparation she wasn’t behind her classmates. And luckily, she knew a few of the students, so she didn’t feel too much like “a little country girl.”

Traveling the eight miles to and from school was difficult on poor roads particularly during bad weather. it would be years before Atlantic Highway would be paved, and 1960 before the town provided transportation to high school. Isabel’s younger sister, Alwilda learned to drive the family’s Ford and picked up other students on her way to high school. Students often boarded with families in town, sometimes working off their board.

That first high school term Isabel lived on Sea Street with her Aunt Mamie and Uncle Lesley Ames, coming home week-ends. Another year, after Merton started high school, the two drove the team in from their farm every day to Mr. Kirk’s livery stable on Tannery Lane, then walked to school on Knowlton Street. That fall Merton was on the football team, so Isabel had to hang around the livery stable every afternoon waiting for him to be done with practice. It would be dark by the time they got home, and there was still homework to do by kerosene lamp.

Each year, even each term, there were different living arrangements. Merton lived over Hasting’s Newstand one year in a little room, opening uup the store before going to school. Isabel boarded with various families; eventually the Ames family moved into Camden for the winter, to a house on Mechanic Street across from the Knox Woolen Mill, and Robie worked there.

Isabel played on the basket ball team, “not first string, but intramurals”, and still has the medals she won in track. She loved Latin, and decided to go to the University of Maine in Orono which offered a Latin major.

Summer at home she found work as a waitress, once at the Green Gables in Camden, and later at the Jack O’ Lantern Tea Room [today’s Whales Tooth Pub] where the waitresses wore black dresses with orange trim. On occasion she tutored one or another of the summer kids in French or Latin.

Upon graduation, Isabel taught Latin at Hamden Academy near Bangor, where she remained for all thirty-nine years of her teaching career. Most week-ends she and her childhood playmate, Elizabeth Griffin, who taught math at Millinocket High School for some forty years, drove home to spend week-ends with their mothers in the houses they grew up in.

Isabel’s photo album shows nieces and nephews, grandnieces and grandnephews playing in the same dooryard she and Merton, Robie, Alwilda, and Edwin played in so many years ago.

Isabel Ames, the last occupant of the old house, lived into her 95th year. In the twenty some years since the house that sat sideways to the Bay, (I recall seeing only one window with a view of the water – a small one at that, facing south as many of the old capes did), slowly deteriorated while the seasons took their toll.

Those old Maine farmhouses take a beating, from generations of children, from the hard and messy work of growing and preserving food, from the very Bay and its weather. No amount of maintenance, painting and repairing, makes much of a difference. These houses are used up. I can say that because I live in one.

Those of us who drove by it regularly knew it probably wouldn’t survive; its lovely location looking out over the Bay doomed it.

Even so, I’m not the only one to recoil at the sight last week of a pile of rubble being hauled away. Where the house Isaac bought with a wheelbarrowful of pennies, where Mary and Robie, Isabel and her siblings worked and played, there’s only a gentle, hay-covered mound to show where it was.

School

Lincolnville Central School staff will be busy all week with Teacher Workshop Days. See the school calendar here. School starts for LCS students Tuesday, September 6. CHRHS freshmen start Sept. 1 with upper classes starting Tuesday the 6th.

Sympathy

Harriette Masalin passed away last week, not long after the Masalin/Carver clan gathered at Maplewood to memorialize Joan Masalin Ratliff, Harriette’s sister-in-law. Condolences to this family.

Think Covid’s Over?

Some eight of us who were at a birthday gathering last week have tested positive this week-end. I was feeling a bit smug at having dodged that bullet, hearing of folks all over town who “had it”. Well, here I sit, waiting out the quarantine period, hoping I haven’t spread it to anyone, alternating between feeling OK and then collapsing on my bed for yet another nap. Actually, if I didn’t know I had Covid, I’d brush it off as a cold and gotten on with life.