Wanderbird after Panther: Retracing a painting expedition to Greenland nearly 150 years on

Karen Miles of Wanderbird Expedition Cruises and Northern Lights Gallery hangs a painting by Lisa Lebofsky made during a voyage loosely retracing the 1869 Arctic expedition of painter William Bradford. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Karen Miles of Wanderbird Expedition Cruises and Northern Lights Gallery hangs a painting by Lisa Lebofsky made during a voyage loosely retracing the 1869 Arctic expedition of painter William Bradford. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

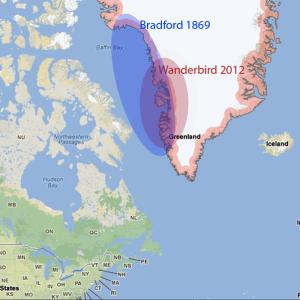

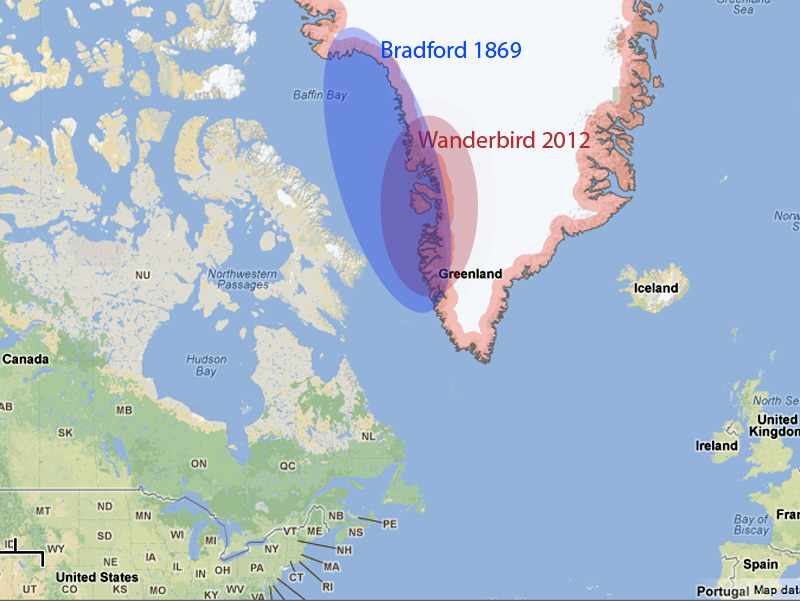

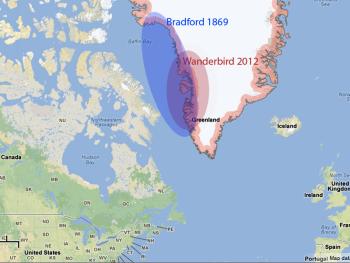

A map showing the general area of travel during the 1869 Bradford Expedition (blue) and last summer's expedition by the Wanderbird (red).

A map showing the general area of travel during the 1869 Bradford Expedition (blue) and last summer's expedition by the Wanderbird (red).

"Ice from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice outside Saqqaq" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice outside Saqqaq" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"View from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"View from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

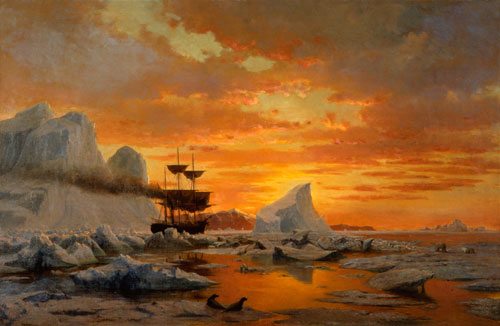

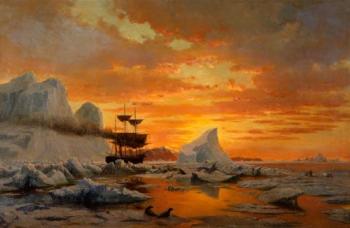

William Bradford's "Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders" c. 1890s, painted from his 1869 expedition to the west coast of Greenland.

William Bradford's "Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders" c. 1890s, painted from his 1869 expedition to the west coast of Greenland.

Small paintings by Lisa Lebofsky. At far left, a retreating glacier peeks between two mountains but no longer reaches the sea (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Small paintings by Lisa Lebofsky. At far left, a retreating glacier peeks between two mountains but no longer reaches the sea (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Karen Miles of Wanderbird Expedition Cruises and Northern Lights Gallery hangs a painting by Lisa Lebofsky made during a voyage loosely retracing the 1869 Arctic expedition of painter William Bradford. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Karen Miles of Wanderbird Expedition Cruises and Northern Lights Gallery hangs a painting by Lisa Lebofsky made during a voyage loosely retracing the 1869 Arctic expedition of painter William Bradford. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A map showing the general area of travel during the 1869 Bradford Expedition (blue) and last summer's expedition by the Wanderbird (red).

A map showing the general area of travel during the 1869 Bradford Expedition (blue) and last summer's expedition by the Wanderbird (red).

"Ice from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice outside Saqqaq" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"Ice outside Saqqaq" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"View from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

"View from Aqajarua" - oil on prepared aluminum by Lisa Lebofsky (Courtesy of Northern Lights Gallery)

William Bradford's "Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders" c. 1890s, painted from his 1869 expedition to the west coast of Greenland.

William Bradford's "Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders" c. 1890s, painted from his 1869 expedition to the west coast of Greenland.

Small paintings by Lisa Lebofsky. At far left, a retreating glacier peeks between two mountains but no longer reaches the sea (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Small paintings by Lisa Lebofsky. At far left, a retreating glacier peeks between two mountains but no longer reaches the sea (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

BELFAST - A group of artists traveling by boat to the Arctic today could be blithely overlooked as a facet of the eco-tourism industry, but in 1869, the year nautical painter William Bradford set sail with two photographers for the west coast of Greenland, it was pretty much unheard of.

Much of the area remains relatively uncharted today, according to Karen Miles of Wanderbird Expedition Cruises, who along with her husband and co-captain, Rick, sailed with a group of photographers, painters, a filmmaker and a writer to the Arctic last summer, loosely retracing Bradford's steps.

But while the landscape maintains a pristine quality, the then-and-now comparisons showed major changes indicative of global warming. The area, in other words, may not get many visitors, but neither is it isolated from its industrialized neighbors to the south.

Bradford started out painting portraits of ships in New Bedford, Mass., in the 1850s and made several trips aboard chartered voyages to Labrador before the 1869 voyage that would make him famous. "The Bradford Expedition," as it became known, was underwritten by a New York businessman and reportedly was the first expedition of its kind solely for art.

Aboard the Panther, a bark with auxiliary steam power, Bradford and company reached Melville Bay on the west coast of Greenland, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, before pack ice forced the vessel to turn back. He later produced an impressive number of larger paintings based on his own oil crayon studies, and roughly 300 photographs taken on the voyage.

In the same spirit, the artists aboard Wanderbird last summer painted, photographed and filmed during the trip, but many also continued working when they returned. The trip was organized by the New Bedford Whaling Museum for a 2013 exhibition titled Arctic Visions: Away then Float the Ice Island.

A selection of paintings made during the trip by New York artist Lisa Lebofsky are currently on display at the Wanderbird-affiliated Northern Lights Gallery in Belfast as part of the exhibition Sedna's Gaze: Inuit Art and Contemporary Arctic Paintings.

Shortly before the show opened, PenBayPilot.com talked to Karen Miles about Bradford's expedition, the challenge of finding the locations he documented 150 years ago, and the changing landscape of the Arctic.

How did the idea of a trip based on Bradford's expedition come about?

We were the vehicle end. Michael Lapides, the photography curator at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, had pinpointed a number of sites along with another artist, Zaria Forman. We were brought into this by Zaria's mom, Rena Bass Forman. Rena had contacted us to travel with her. She's an amazing photographer. And in the time that it took us to put this all together, she had a terminal condition and succumbed to it. Her daughter was the one who moved forward with putting artists together.

Was finding the Bradford sites the principal idea?

It was a little bit of a memorial to Zaria's mom. They called it Chasing the Light: In the spirit of the Bradford Expedition. So we were looking for sites and we identified sites. But then [for example] near the end of the trip we were on the back side of Qerqertarsuaq and we found an old sod house, and even though we really wanted to push to get on to this next Bradford site so we could get in one more site before the trip ended, everyone wanted to stop and explore this area where there was an abandoned sod house. Things like that occured daily.

So you were playing it a little by ear.

You have to, because the weather can be really intense. It comes on strong and fast and intensely, and add ice to it and a lot of it is traveling by the weather.

We didn't have a longitude and latitude to say where this iceberg was [pointing to a Bradford painting reproduction], but we looked at the communities where he visited. The names have changed significantly, multiple times. There's the outsiders' version of the spelling of the Inuktitut name, or Greenlandic name. Then later the names were changed to Danish. And recently, with Greenland receiving a bit more autonomy, the names have all changed back to Greenlandic and gone to the proper Greenlandic spelling. So, it was challenging to find the places.

What names did they have when Bradford went?

They were Inuktitut names but they were varied spellings, so there's a place called Qaarsut, and on our paper charts, our electronic charts, the Bradford book and in other sources each one had it spelled a different way. So basically you can figure out what it is, but there are three or four different spellings.

One of the sites we came upon by accident. We were looking very intensely for a mountain he had photographed traveling through literally an uncharted fjord in the area of Upernavik. On the chart there was just a single strand of numbers [depth soundings] that the cargo ferries followed, and other than that it's a blank sheet of paper with no numbers. We think of the world as being fully charted and everything being discovered but there are a lot of uncharted waters, or loosely-charted at best.

We anchored at the best place to anchor from a navigational standpoint. It was sheltered and a good place to get out of the wind for the night. The next day we went hiking and spent the afternoon ashore, where folks were painting and doing their thing. On the way back to the boat, we looked out toward the entrance to the fjord and we realized we were standing in the exact location we were looking for, and we had found it fully by accident, just by thinking in terms of prudent navigation the best place to go for the night, as though the skipper of the Panther had had the same thought all that many years ago.

When you're comparing the landscape today to Bradford's photos, is it rock you're looking at, or ice?

It's not ice, because the ice has changed dramatically. It's the mountains. The stone. The faces, and the shapes lining up exactly, and if you have the general lay of the land you can find those sites, but it isn't necessarily easy.

Many of his paintings include icebergs or glaciers. Are there ice formations that have remained enough the same that you can identify them?

Certainly they'll change throughout the year, but in August when we went, something that might have been a glacier running down into the ocean during Bradford's time is now a little patch. [She showed an example of this in one of Lebofsky's paintings — a strip of ice running down from a mountain but stopping far short of the sea].

Assuming that global warming is happening, how do you establish causality in a particular case?

It's not cause and effect, but you can see that glaciers have retreated when you look at then and now.

The biggest changes we know about are from asking Greenlandic and Inuit community elders. People in the generation over 50 years old have seen very dramatic changes, not being able to go to their hunting caverns because there's no longer sea ice.

Last winter we were told by locals that for the very first time the harbor stayed open [unfrozen] all winter. Before it was the bay, now it's the harbor in Aasiaat.

Is that like Belfast Harbor as compared with Penobscot Bay?

Yeah, say Penobscot Bay used to always freeze over, 15 years ago, and Belfast Harbor, well that's a given, it always freezes. So Penobscot Bay used to freeze 15 years ago but now for the very first time Belfast Harbor didn't freeze. And that's what's happened with one small community on Disko Bay.

There used to be a winter fishery there 15 years ago that was done by dogsled. You take your Komatik, your sledge, out on the ice, fish through the ice for halibut, then land your catch by dogsled back in the community. And there's no longer ice to support dogsled winter travel.

What was the word you used for dog sled?

In Canada it's "Komatik." I have one almost finished and it will be on display in our window [at Northern Lights Gallery].

You're making one, full size?

A one-dog version, because I have a Labrador Husky that was given to me by an Inuit family. She loves to pull. I'm hoping we'll have enough snow that I can take it to Hannaford or the Coop and she can pull my groceries home.

What about ice? What happens if your ship hits an iceberg? Is it like hitting a rock?

It is like hitting a rock. So we don't. We were traveling around, through ice, and we were watching the weather really carefully because you don't want to be in an area where the ice is compressing. So you have to be extremely, extremely careful in these areas.

One of our favorite lines is: We need to know about anything larger than a basketball.

Were there certain things that attracted people to say, let's stop here, or where they got out their materials and started working?

The coach house was covered with art materials and then we'd need to serve a meal and everyone would shuffle their things down under the seats and we'd have a meal and they'd go right back to painting. We had a lot of evenings like this [points to a reproduction of Bradford's Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders, which shows a sailing ship amid icebergs at sunset], where you'd have a blazing orange sunset against blue ice for a very long time and you'd think it's at its peak and then it goes on and on and on and it gets more intense.

And then the are times where it's more subtle. We were in an area where there were a lot of icebergs that had been around for a while and the center of gravity is really close [to the center] so they spin. So you're traveling through and there are icebergs spinning 360 degrees [end over end] and they go very slow and then they might speed up a little. A spinning iceberg often drags on the bottom, and if you have a lot of rocks that's the pattern on the top of a spinning iceberg [pointing to one of Lebofsky's paintings showing what looks like a grooved hilltop]

It's almost like what happens to land when a glacier goes over it.

Yeah, It looks like glacial fluting, exactly. And you see that too because there's not a lot of vegetation.

Ice is really fascinating. It's popping and cracking and tinkling. It comes in many colors. There's clear ice, which is really intimidating if you're moving a boat. There's ice that's blue, it can have really intense blue stripes, it can appear white. It's unstable and sometimes like [Lebofsky's painting], the icebergs spin, and sometimes you're in areas where you hear sounds that sound like gunshots, and you might not even see it but you hear gunshots and cracking and rumbling. It's a pretty mesmerizing place with a lot of inspiration.

It seems cold to be painting outside. What's the ambient temperature on a sunny day?

It actually can be quite nice. You can be out in trousers and a sweater.

So you're not totally bundled up?

You can be. There are days.

Ethan Andrews can be reached at ethankingcole@gmail.com.

Event Date

Address

33 Main Street

Belfast, ME 04915

United States