Rockport: Fishermen, scientists track effects of rising ocean temperatures

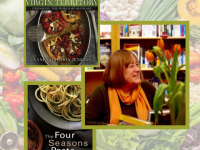

The 38th Annual Fishermen's Forum was held Feb. 28 to March 2 at the Samoset Resort in Rockport. Fishermen and scientists agree now that fisheries must be monitored, analyzed, tracked and better understood in order for the industry's long term sustainability. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The 38th Annual Fishermen's Forum was held Feb. 28 to March 2 at the Samoset Resort in Rockport. Fishermen and scientists agree now that fisheries must be monitored, analyzed, tracked and better understood in order for the industry's long term sustainability. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

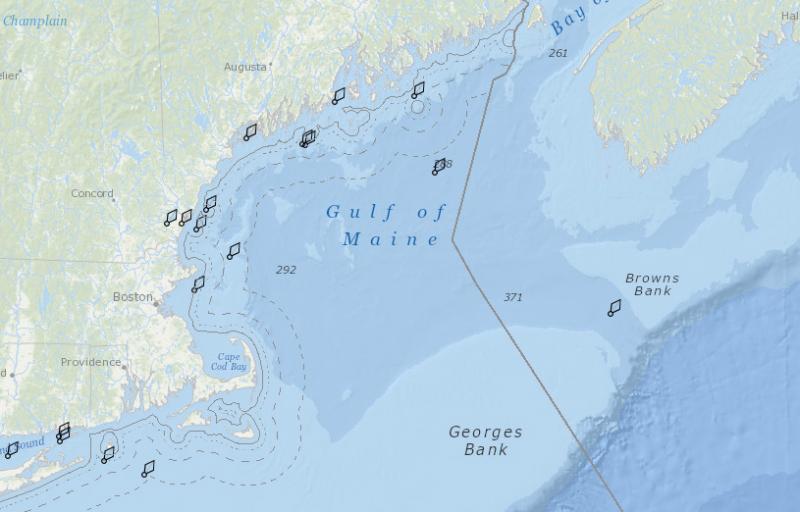

Buoys with sensors for all manner of data collection are located throughout the Gulf of Maine and down the coast to Long Island.

Buoys with sensors for all manner of data collection are located throughout the Gulf of Maine and down the coast to Long Island.

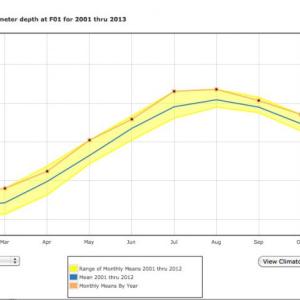

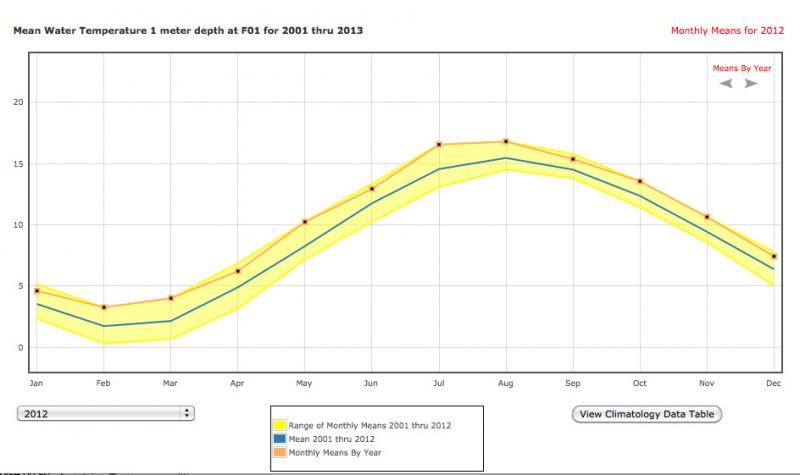

Last year (2012) was an extraordinary year in temperature, scientists said.

Last year (2012) was an extraordinary year in temperature, scientists said.

The 38th Annual Fishermen's Forum was held Feb. 28 to March 2 at the Samoset Resort in Rockport. Fishermen and scientists agree now that fisheries must be monitored, analyzed, tracked and better understood in order for the industry's long term sustainability. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The 38th Annual Fishermen's Forum was held Feb. 28 to March 2 at the Samoset Resort in Rockport. Fishermen and scientists agree now that fisheries must be monitored, analyzed, tracked and better understood in order for the industry's long term sustainability. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Buoys with sensors for all manner of data collection are located throughout the Gulf of Maine and down the coast to Long Island.

Buoys with sensors for all manner of data collection are located throughout the Gulf of Maine and down the coast to Long Island.

Last year (2012) was an extraordinary year in temperature, scientists said.

Last year (2012) was an extraordinary year in temperature, scientists said.

ROCKPORT — A longterm warming trend of the Gulf of Maine waters is underway, scientists agree. And on top of that, a more recent rate of change has dramatically increased. Data collected at multiple buoys between the shore and Browns Bank deliver data confirming warmer waters; yet, what will happen to the fish, and the fishing industry, remains hypothetical as scientists look at the entire Atlantic Ocean, its currents and ecology. In the meantime, Maine fishermen watch for emerging trends... and cope with change.

And, they provide the anecdotal evidence of how marine life may be adjusting to rising water temperatures. They help document patterns, such as where lobsters thrive, and the size of the shrimp and cod catches. They spot where whales and other sea mammals visit, and when fish spawn. Together, the fishermen and scientists are watching and recording, and talking, as they witness a shift of Atlantic cod and other fish towards the cooler northeasterly waters, with some even disappearing.

More from the 38th Annual Fishermen's Forum:

Acidification, warmer water a dangerous combination

Lobstermen pursue union, seek clout before Legislature

This past weekend, Feb. 28 to March 2, the 38th annual Maine Fishermen's Forum at the Samoset Resort in Rockport drew several thousand participants and exhibitors to discuss not only the health of Gulf of Maine waters, but other topics that affect the business of commercial fisheries. Sessions held over the three-day forum touched on ocean acidification, advances in lobster science, gear conflicts and how to avoid them, ocean renewable energy, and closed scallop areas. They talked about clamming and shellfish, and they talked about aquaculture leasing. Their children swam in the pool and watched movies while adults visited, learned, and bid at an annual auction. They connected for three days, those people of the Maine coast who spend their lives on the water, or at the water's edge.

The forum is the yearly gathering for fishermen from up and down the coast to meet with each other, as well as salesmen and tradesmen of the industry. Some bankers were there, as well as marine law enforcement and politicians. And there were the marine scientists, who, over the past 20 years, have steadily increased their monitoring and analysis of the of the gulf and the Atlantic Ocean.

Government agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, as well as universities have stationed monitoring buoys and sensors on the gulf and down toward Massachusetts Bay and the Long Island Sound, testing temperatures, wave action, wind speed, salinity. They even listen for the Right Whales in Massachusetts Bay. Their sensors take measurements at the ocean bottom, mid-column and at the water's surface.

"They all do different things," said Tom Shyka, a panelist at the Saturday forum seminar, "Changing Ocean: What Changes Are We Observing in the Gulf of Maine and What Does It Mean for the Ecosystem?"

Shyka is an outreach and communications specialist for the Northeastern Regional Association of Coastal and Ocean Observing System (NERACOOS), a collaboration of scientists and organizations who synthesize and interpret a vast collection of data from the sentinel monitoring.

NERACOOS provides a wealth of online data, mapping everything from human demographics to marine geological formations. It is possible to even dial a buoy and check the weather and ocean conditions at certain spots, 24 hours a day over a touch-tone or cell phone thanks to a partnership with the National Data Buoy Center’s Dial-A-Buoy service.

This synthesis of data has been underway for a decade, but its current level of sophisticated presentation is recent. The NERACOOS website includes the ability to overlay data sets from satellites to historical research to ocean forecasting, even coastal flooding forecasts.

Before a roomful of approximately 30, Shyka cited an article by Morrison et al, Rapid Detection of Climate Scale Environmental Variability in the Gulf of Maine, where analyzed changes were recorded at all depths, noting that the higher rate of water temperature change was at the midwaters. While that study noted a spike in water temperature during the 1940s, followed by a rapid cooldown in the 1950s, there has been a steady rate of warming over the past seven years with a much high rate of change in addition to the long term trend.

In 2011, the average water temperature began to increase at the end of the year, and throughout 2012, the buoys were recording readings "well above the average temperature," he said.

While calculating the data involves closely watching the anomolies, "the trend of anomolies suggest the water temperature is warming," he said.

For instance, a buoy located in Penobscot Bay recorded in 2012 a mean water temperature in March of 39.2 degrees Fahrenheit. The mean water temperature for 2001 to 2011, however, in March, is 35.85 Fahrenheit.

Shyka cited an article by Andy Pershing, Cod in the Gulf of Maine, who analyzed changes are recorded at all depths, noting that the higher rate of change is at the midwaters.

Last May, scientists at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Boothbay and the U.S. Geological Survey reported significant changes in the Gulf of Maine ecosystem due to increased amounts of rainfall and volumes of river discharge.

Panelist Jeffrey Runge, a scientist at the Gulf of Maine Research Center, referenced other studies recording increases in water temperature. He described the 100-year warming trend of annual increases of 0.01 degrees centigrade. But since 2004, that annual rate of change has increased 10 times the 100-year trend, he said, from 0.1 to 0.3 centigrade per year. In rough translation, that describes the mean temperature of gulf waters increasing over the past eight years by approximately four degrees Fahrenheit.

He indicated that increases in major precipitation weather events and subsequent freshwater discharge is another change that affect the coastal waters of the Gulf of Maine.

And, he said, "the transport dynamics has changed."

The transport dynamics include the change of currents from waters flowing in and out of the Gulf of Maine through the Northeast Channel and the eastern Scoatian Shelf that originates from the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Labrador. There is now an increase of fresher coastal inflow, bringing what has been termed in a 2011 paper, Regime Shift in the Gulf of Maine.

"At some point between the year 2000, when the last Bedford Institute of Oceanography GLOBEC mooring was removed from the eastern NEC, and 2004, when a new mooring was placed there as part of the U.S. ocean observing array, a transformation occurred," the authors said.

That change in currents at bottom depths suggested to them that important consequences would affect the Gulf of Maine ecosystem.

Runge is particularly interested in the fate of calanus finmarchicus, the lipid-rich zooplankton, which, according to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, assemble as copepods: "A class of crustaceans with over 7,500 species, most of which are marine. Copepods are small (only a few species over 1 mm) and extremely abundant, often dominating the plankton community. They form a link in the food web between the primary-producing phytoplankton and the plankton-feeding fish like Atlantic herring. Almost all fish found in temperate and polar waters rely at some point in their life cycle on copepods and other shrimp-like zooplankton (krill) as a food source. In addition, some larger organisms feed directly on copepods."

They thrive in Wilkinson Basin and the Great South Channel of the Gulf of Maine.

"There's a reason why the Right Whales like the Gulf of Maine," said Runge.

Those calanus finmarchicus also, "constitute 75 percent of the diet of herring in GOM in the summer," he said. "This one species is an important part of GOM."

And the copepods thrive in an isotherm with temperatures of 10 degrees C.

From 1960 to 2000, that isotherm was below the Gulf of Maine, but is projected to shift northward, according to a 2012 study by French scientists, "Causes and projections of abrupt climate-driven ecosystem shifts in the North Atlantic."

The study shows that where a critical thermal boundary exists — such as that isotherm where codepods thrive — even small temperature increases trigger abrupt ecosystem shifts.

"This large-scale boundary is located in regions where abrupt ecosystem shifts have been reported in the North Atlantic sector and thereby allows us to link these shifts by a global common phenomenon," the study said. "We show that these changes alter the biodiversity and carrying capacity of ecosystems and may, combined with fishing, precipitate the reduction of some stocks of Atlantic cod already severely impacted by exploitation."

"That's a potential concern," said Runge.

But he offered a competing theory, suggesting that calanus finmarchicus will be sustained by the inflow of calanus from the Bay of Fundy and the Scotian Shelf.

Further south of the Gulf of Maine, warming waters have already triggered more drastic results. The warm summer of 2012 caused the entire water column in Long Island Sound to heat up so much that the nuclear reactor at Millstone Nuclear Power Station in Waterford, Conn., was forced to shutdown. The water temperature, according to NERACOOS, was "above the permitted temperature allowed for cooling."

Those warm waters also are attributed to encouraging an abnormally large red bloom in Long Island Sound.

As the scientists watch the Gulf in this warming trend they are concerned that increased water temperatures could affect the biological clocks of marine species, which spawn at specific times of the year based on environmental cues like water temperature.

"Anyone who spends time on the water has seen changes in less than two years," said Steve Train, panel moderator, and captain of the Wild Irish Rose, encouraging his colleagues to pay attention to what they witness out on the water.

Other relevant links

National Weather Service

New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Coastal Program

NextEra Energy Seabrook Station

PREP (Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership)

UMB center for Coastal Environmental Sensing Networks (CESN)

Event Date

Address

United States