New standards would require all Maine libraries to pay directors, expand hours of operation

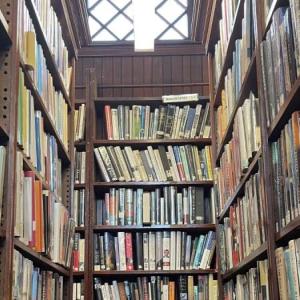

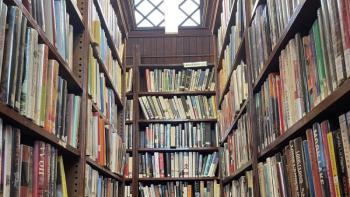

Under the proposed Maine Regional Library System Public Library Agreement to Participate, libraries would be required to meet the Maine State Library’s definition of a “public library.” Those that do not — which now includes many small libraries — would be reclassified as “limited-service libraries.” Photo by Joyce Kryszak.

Under the proposed Maine Regional Library System Public Library Agreement to Participate, libraries would be required to meet the Maine State Library’s definition of a “public library.” Those that do not — which now includes many small libraries — would be reclassified as “limited-service libraries.” Photo by Joyce Kryszak. Under the proposed Maine Regional Library System Public Library Agreement to Participate, libraries would be required to meet the Maine State Library’s definition of a “public library.” Those that do not — which now includes many small libraries — would be reclassified as “limited-service libraries.” Photo by Joyce Kryszak.

Under the proposed Maine Regional Library System Public Library Agreement to Participate, libraries would be required to meet the Maine State Library’s definition of a “public library.” Those that do not — which now includes many small libraries — would be reclassified as “limited-service libraries.” Photo by Joyce Kryszak.The Maine Library Commission is expected to consider a proposal Monday that would require public libraries to sign an agreement so they can maintain access to interlibrary loan services and internet access.

Under the proposal, all libraries would be required to pay their directors and remain open to patrons at least 12 hours per week or risk losing those services.

Several nonprofit libraries, long operated by volunteers with limited hours, are pushing back against the proposed requirements, saying they cannot afford them on tight budgets. They say they do not want to be forced to choose between paying salaries or shutting down.

The new requirements stem from an overhaul of library standards by the Maine State Library, separating out provisions already mandated by state or federal law, including those related to wages.

Marijke Visser, director of library development for the Maine State Library, said libraries have previously paid stipends to directors instead of full salaries. But under state and federal wage and hour laws, “you can’t do that,” she said. “Once you’re an employee, you have to be paid as an employee, and a stipend does not cut it.”

She acknowledged that many libraries are now run by volunteers, but said the practice “goes against wage and hour laws, and we’re righting that ship so that libraries will be in compliance with those laws.”

That does not sit well with Colin Windhorst, chairman of the Lincoln Memorial Public Library in Dennysville, who also serves as the library’s unpaid director. The nonprofit library, housed in a small, town-owned building, is run entirely by volunteers.

Windhorst said he worries that if the library does not meet the proposed requirements, “we will no longer be a part of the Northern Maine Library District.”

He called the potential loss of van delivery service and e-books “unthinkable.”

“Our relationship with the Maine State Library has allowed us to provide services to this community for years,” Windhorst said.

“It is blood, sweat, toil and tears to run a library in a small community,” he said, adding that the requirement for paid directors and expanded hours creates “a set of standards for the haves, not the have-nots.”

Under the proposed Maine Regional Library System Public Library Agreement to Participate, libraries would be required to meet the Maine State Library’s definition of a “public library.”

Those that do not — which now includes many small libraries — would be reclassified as “limited-service libraries.”

A limited-service library would not be eligible to participate in the Maine Regional Library System’s reciprocal borrowing program or van delivery service for interlibrary loans. It would also lose access to e-books and e-audiobooks through a Maine Infonet Workload Library subscription, free and low-cost staff training, internet connection subsidies, technical support and Ancestry Library Edition services offered through the Digital Maine Library.

If library commissioners adopt the proposed agreement, libraries would be required to sign and return it by Jan. 1.

“Libraries are part of the social fabric of small communities, and people access them and their services — and they do,” Windhorst said, adding that the access is critical to residents of Dennysville.

In nearby Pembroke, Carol Wolf, vice president of the Pembroke Library Association, called the proposed agreement her library would need to sign to maintain current services a real threat to the community.

The Pembroke library is a nonprofit that relies on grants, donations, used book sales and other fundraisers to meet its $23,000 annual budget. The town contributes a small stipend each year — $1,000 for 2025.

“Our library is run by 10 dedicated, unpaid volunteers,” Wolf said. Five of the volunteers also serve as library trustees, and the library cannot afford to conduct an annual financial audit — one of the new requirements for eligibility under the Maine Regional Library System.

As many as 50 libraries will be impacted

There are 257 public libraries in Maine. According to a 2023 database of Salary and Benefit Statistics for all Maine Libraries, 20 operate with unpaid directors, and others offer small stipends — some as little as $1 per year.

That means about 10 percent of public libraries would need to begin paying directors or risk losing services.

“We’re very much aware that there are some libraries that will not be able to sign off on the new agreement,” Visser said. “To recognize that, we want to make it crystal clear that if they don’t sign the agreement by Jan. 2, services are not going to be cut off on Jan. 3.”

Instead, a subcommittee of the Maine Library Commission — including members of the commission, the Maine Library Advisory Council and other representatives — will develop what Visser called a collection of “wraparound services” to help libraries move from where they are to “where they need to be.”

Visser said the commission recognizes that paying library salaries will require funding, and support will be available to help struggling libraries advocate for additional money from towns, patrons and other donors to cover salaries and expand service hours.

Visser said an estimated 50 libraries would be affected by the new rules, though some of the changes are minimal, such as requiring email addresses and updated websites.

“The majority of our libraries are small and rural,” Visser said. “They serve populations of 5,000 or fewer, and many are one-person operations.”

Knowing this, the Maine Library Commission plans to give libraries three years to become compliant.

“As long as the library is making a good faith effort to do whatever it needs to do,” Visser said, “then there isn’t any reason why we wouldn’t continue working with them.”

Wolf of the Pembroke Public Library said she learned about the proposed agreement recently, after a member of the library’s book club attended one of the Maine State Library’s listening sessions Oct. 28 at the Merrill Library at the University of Maine at Machias.

The meeting was part of a 10-stop statewide tour to discuss new models, practices and services, including revised Benchmarks of Excellence adopted earlier this year and the proposed agreement for libraries to join the newly formed Maine Regional Library System. If there was any communication to libraries directly from the Maine Library Commission alerting them to the proposed agreement, Wolf said she was not aware of it.

In September, state library commissioners approved a new regional model that consolidates Maine’s nine library regions into a three-tiered Maine Regional Library System. Maine’s libraries are now divided into northern, central and southern regions, a move intended to improve library services.

Some of Maine’s smallest library directors say the proposed agreement required to join the new Maine Regional Library System could have the opposite effect, creating hardships for cash-strapped nonprofits by requiring paid directors and extended hours, potentially diminishing services in their communities.

Wolf said the feeling among small-town library directors after hearing about the proposed agreement is that “it will destroy many small libraries. That’s a fact.” She added that the greatest concern, if that were to happen, is that “it’s the small libraries in the remote communities that most need these services.”

The “proposal would deny internet access to many residents of northern and Downeast Maine, limit literacy and harm communities in areas that are already isolated and struggling financially,” Wolf said, citing the lack of a paid library director.

In addition to Pembroke and Dennysville, libraries in Washington County that could be affected by the paid director requirement include the Danforth Public Library and the Louise Clements Library in Cutler.

The Danforth Public Library, which is open three hours a week, falls well below the proposed 12-hour minimum — as do many libraries across the state, including the Mayhew Library in Addison, which is open nine hours per week.

In Somerset County, the Jackman Public Library is open six hours a week and operates with an unpaid director, as does the Stewart Public Library in Anson.

“We are a small, all-volunteer library existing on basically $12,000 a year,” Emily Quint, director of the Stewart Public Library, said. “There is no way that the board can pay” a director’s salary under the current budget.

In 2023, Quint accepted a one-time $100 stipend.

“We have been here for well over 100 years,” Quint said, “and we’ve always been all-volunteer.”

Volunteers are able to keep the library open 10 hours a week, Quint said, but that is becoming more difficult as volunteers are increasingly hard to find.

In nearby Bingham, where the library is open 12 hours a week and Director Carla Small is unpaid, Small said she has heard that libraries could soon be required to pay their directors, a change she believes is appropriate because directors often work well beyond the hours their buildings are open to the public.

Bingham Union Library Treasurer Rachel Tremblay said Wednesday she was not aware of Monday’s vote, and noted that the time between the vote and the Jan. 1 deadline for libraries to sign agreements does not leave much time to budget. The library, which serves three towns, typically makes its appropriations request at the end of the year for about $15,000.

Tremblay serves as the unpaid treasurer, as do many at small libraries, and said requiring libraries to pay wages to maintain access to van deliveries and e-books is a lot to ask of nonprofits that rely heavily on volunteers.

“It sounds like a punishment for people who are volunteering, instead of being grateful that these libraries are still running because of volunteers,” Tremblay said. “There are only so many of us, and we’re all old” — a common refrain among volunteer-run libraries.

Elsewhere in Maine, the Whitman Memorial Library in Woodstock in Oxford County is open Mondays and Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., just meeting the 12-hour requirement under the proposed agreement. The same goes for the Weld Free Library in Franklin County, which is also open 12 hours a week. However, neither library would meet a 15-hour threshold under the Benchmarks of Excellence, a document that is separate from the proposed agreement.

The benchmarks also require that libraries have a bathroom, which Windhorst said the Lincoln Memorial Library lacks.

The library building, built in 1912 without a bathroom, is too small to add one without an expansion. As a result, patrons, including children who attend weekly programs, use the bathroom at the church hall across the street.

Another requirement is that, on average, library collections budgets must have increased over the past three years, a benchmark many small libraries have not met.

Windhorst said his library “may be able to squeak through the approval process by adjusting our public hours, etc., but they still impose incredible burdens on providing library services to rural communities like ours.”

Visser, the director of library development for the Maine State Library, said the benchmarks were built from standards the library commission previously had in place, so they are not entirely new to libraries. She said the revisions are intended to serve as a strategic planning document to help guide libraries into the future.

In Pembroke, Wolf said — as is true in many towns — the library is more than a place for books; it serves as a free community hall.

“In Pembroke, there are no cafes, no places for people to gather other than church basements and the American Legion,” she said. “However, the library has a large community room used regularly by quilting groups, knitters, an astronomy club, the St. Croix Gardeners’ Club, the Quoddy Connection singers, Friends of Moosehorn, chantey singers, hospice volunteers and the Girl Scouts, among others.”

In a strongly worded letter signed Wednesday by the Lincoln Memorial Public Library’s board of directors in Dennysville, the board told the Maine Library Commission: “You would be failing in your responsibility by approving an agreement that places an impossible burden on those least able to bear it. Our libraries in Maine, great and small, play a key role in the social transformation of our communities.”

Another requirement — that all libraries, regardless of budget, have paid directors — “will create an impossible set of circumstances for us and countless other small rural libraries that depend on volunteers to act as ‘citizen librarians’ in our communities,” the board wrote.

The Maine Library Commission is scheduled to meet via Zoom at 1 p.m. Monday, Nov. 17, to consider adopting the proposed Maine Regional Library System membership application agreement.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit civic news organization. To get regular coverage from The Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.