Here’s what you need to know about Maine’s two ballot questions this November

Mainers will see two big questions on the ballot this year: one about election procedures, and one about a potential red flag law.

Maine citizens can put proposed legislation directly before voters through a process called a citizen initiative. For a citizen initiative petition to be approved by the Secretary of State’s Office, petitioners must collect the signatures of registered Maine voters equal to at least 10 percent of the votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election, which in this case was at least 67,682. The petition then goes to the Legislature, which can choose to enact the bill as written or send it to a statewide referendum.

On Nov. 4, Maine voters will decide on two referendum questions brought by coalitions of citizens through this process: one that would change voter ID and absentee voting rules and one that would create a process by which family members could petition the courts to temporarily remove weapons from an individual at risk of harm to themselves or others.

As in-person absentee voting begins this week, here’s what you need to know:

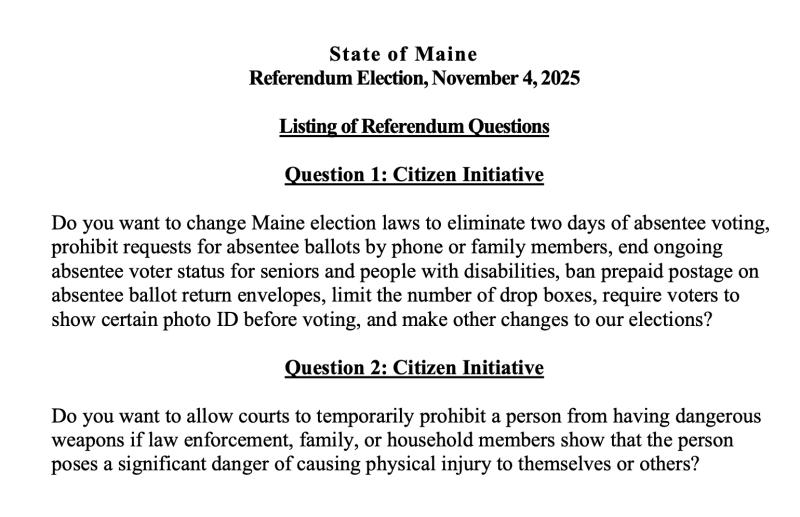

Question 1: “An Act to Require an Individual to Present Photographic Identification for the Purpose of Voting”

Do you want to change Maine election laws to eliminate two days of absentee voting, prohibit requests for absentee ballots by phone or family members, end ongoing absentee voter status for seniors and people with disabilities, ban prepaid postage on absentee ballot return envelopes, limit the number of drop boxes, require voters to show certain photo ID before voting, and make other changes to our elections?

This referendum question was brought forward by a coalition that calls itself Voter ID for ME. The proposed legislation would make a number of changes to the way votes are cast in Maine.

It would require all voters to present photo identification in order to vote in-person or absentee, and would allow voters from the same municipality to challenge the validity of another person’s ballot for alleged failure to comply with the ID law or for a non-matching signature on an absentee ballot envelope. Exceptions would only be granted if someone had religious objections to being photographed.

Valid forms of photo ID would be limited to a Maine driver’s license, non-driver identification card, or interim identification card; a U.S. passport or passport card; or a military or veteran identification card. Voters would not be able use a student ID, Tribal ID or Maine Department of Corrections-issued ID.

The legislation would also make significant changes to absentee voting procedures. In addition to requiring photo ID from those requesting an absentee ballot, election officials would also have to issue an “identification envelope” with all absentee ballots for voters to fill out with information, including their political party affiliation and ID.

If passed, Maine’s current laws that allow an immediate family member to request an absentee ballot on behalf of a voter and make it possible for a voter to request an absentee ballot by telephone would be repealed.

Instead, voters would be required to request an absentee ballot electronically or in person themselves, though they could still designate someone else to return a ballot on their behalf. The proposed changes would also eliminate two days of absentee voting.

Maine’s current ongoing absentee voter enrollment program, in which a senior or person with disabilities can register once to vote absentee and is automatically sent an absentee ballot each election thereafter, would be repealed. Voters, regardless of age or ability, would have to request an absentee ballot for each election.

The proposed law would also limit each municipality to one drop box, designate one municipal office at which election officials could accept absentee ballots, prohibit election officials from including prepaid return postage with an absentee ballot and would bar the Secretary of State’s Office from charging a fee for non-driver identification cards, which are currently sold for $5 each.

The Legislature’s nonpartisan Office of Fiscal and Program Review estimated that the free non-driver ID cards would decrease the state’s highway fund by about $29,000 annually. The Secretary of State’s office, according to OFPR, estimated the voter ID requirement would cost the state more than $1.3 million the first fiscal year and about $156,000 every following year.

The law would go into effect on January 1, 2026.

Supporters

The Maine-based conservative political action committee The Dinner Table is behind the citizen initiative. Alex Titcomb, who co-founded the group with state representative Laurel Libby (R-Auburn), said the proposed law emerged out of “election integrity issues.”

He emphasized that Question 1 is meant to be “future-looking,” and said he believes it will increase the “security and transparency of the election process.”

It’s also about fairness, he said, explaining that every municipality and every voter should start on a level playing field. That means every town should get one drop box, regardless of size, he said, and that people who want to cast absentee ballots should have to make that request themselves.

“I can’t go in on election day and go in line and ask, ‘Hey can I have my ballot and my wife’s ballot and go take care of it?’” But Titcomb said he can request both his and his wife’s absentee ballots, which he did last year and finds unfair to people who aren’t voting absentee.

Same goes for requesting an absentee ballot by phone.

“Every person should request their own ballot, and there should be a paper trail,” Titcomb said.

He called the opposition’s campaign “fear-mongering.”

“Maine people are smart people and they’re independent people,” Titcomb said. “Every person that wants to cast a ballot will figure out how to cast a ballot.”

The Maine Republican Party supports the proposal.

Opponents

David Farmer, the campaign manager for Save Absentee Voting, said Question 1 is a “clear attack on absentee voting in Maine.” While the campaign spearheaded by Titcomb is called Voter ID for ME, the majority of the proposed legislation has to do with absentee voting, Farmer said.

Among his coalition’s concerns are the “new and onerous restrictions” on election officials and the reduction of local control.

“This is a voter suppression measure. It’s meant to reduce the number of people who participate,” Farmer said.

Absentee voting has been around in some form for more than a hundred years, he added, and has proven to be safe and secure. Question 1, if passed, would put up “new hurdles,” particularly for seniors, people with disabilities and people in rural areas who Farmer said “disproportionately use the absentee voting system.”

He added that he encourages all voters to read the full proposed legislation before heading to the ballot box.

“They’re putting in new restrictions to how people access absentee voting and they’ve used language that’s unclear in its intent and purpose,” he said.

Members of the Save Absentee Voting coalition include the ACLU of Maine, Disability Rights Maine and the Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition, among several others. The Maine Democratic Party also opposes the proposal.

Question 2: “An Act to Protect Maine Communities by Enacting the Extreme Risk Protection Order Act”

Do you want to allow courts to temporarily prohibit a person from having dangerous weapons if law enforcement, family, or household members show that the person poses a significant danger of causing physical injury to themselves or others?

If voters approve this question, it would enact an Extreme Risk Protection Order Act, which would create a process by which family members or law enforcement could petition the courts to temporarily remove weapons from an individual at risk of harm to themselves or others and temporarily prohibit them from possessing or purchasing firearms.

Extreme risk protection orders are already in Maine statute, currently as a one-of-a-kind yellow flag law, which went into effect in 2020. Under the current version of the law, only law enforcement officers have the ability to submit a court petition to temporarily take away a person’s weapons.

Under the yellow flag law, a law enforcement officer must first bring a person into protective custody, which is different from arresting someone, and obtain a behavioral health practitioner’s assessment that a person may hurt themselves or others. Only then can they bring a weapons restriction order (also called an extreme risk protection order) to a judge or justice for final approval.

Following the mass shootings in Lewiston in 2023, state lawmakers passed a bill that, among other changes, gave law enforcement officers the ability to obtain a warrant to take someone into protective custody.

There are two key differences between the proposed red flag law and the current yellow flag law: one is that family or household members, in addition to law enforcement, could file a petition requesting the court issue an extreme risk protection order; the second is that a red flag order would not require a behavioral health assessment.

If passed, the proposed legislation would add the red flag law to Maine statute without repealing the yellow flag law, meaning Maine would have two different methods of temporarily confiscating weapons from people deemed to be a danger.

If the red flag law passes, the Administrative Office of the Courts, via OFPR, estimated a one-time cost of $76,000 to the Maine Judicial Branch for “significant system programming updates” and temporary staffing to implement it.

The administrative office estimated that the red flag law would require an additional annual appropriation of approximately $1.1 million to establish six new positions “to handle the increased workload expected to be generated.” OFPR also noted state and local law enforcement agencies may see increased costs for the collection and storage of firearms.

The law would go into effect 30 days after the governor makes a public proclamation of the result, which must be within 10 days of the election. The governor has no veto power on legislation enacted via a citizen initiative.

Supporters

Jack Sorensen, the spokesperson for the Safe Schools, Safe Communities initiative that submitted the petition for Question 2, said red flag laws have been “proven effective at saving lives, disarming people who threaten mass shootings, including school shootings, and reducing suicide.”

Twenty-one states have red flag laws, according to the National Extreme Risk Protection Order Resource Center at John Hopkins University.

Sorensen called the current yellow flag law, which went into effect in 2020, an “experiment” negotiated by the governor, lawmakers and gun rights lobbyists.

“The experiment failed in Lewiston, horrifically and tragically, despite the fact that the gunman’s family knew he was dangerous and repeatedly warned law enforcement,” he said.

Giving family and household members, who may be the first to notice concerning behavior, the ability to directly petition the court “adds a tool to the toolbox,” he said, noting that families may not want to get law enforcement involved immediately out of fear that it could escalate a situation.

In response to opponents’ argument that a red flag law diminishes a person’s right to due process, Sorensen pointed out that subjects of a red flag order still get their day in court: Once a petition is filed, the court must schedule a hearing within 14 days to determine if there is a preponderance of evidence that the person poses a significant risk before approving the order.

Family or law enforcement can also petition for an emergency extreme risk protection order, which does not require that the subject be given prior notice before an order is approved. A hearing is still required within 14 days of when the order was issued.

Supporters of the proposed red flag law include the Maine Gun Safety Coalition (the sponsor organization behind Safe Schools, Safe Communities), many of the state’s professional medical organizations and the Maine Education Association.

Opponents

Opponents of Question 2 said that the proposed red flag law is not only unnecessary, given what they called the yellow flag law’s success, but infringes on due process and personal liberty.

As of late September, Maine law enforcement agencies had completed nearly 1,100 yellow flag orders since the law went into effect in 2020. David Trahan, executive director of the Maine Sportsman’s Alliance, said this is evidence that the yellow flag law is working. Law enforcement cited threats of suicide in three-quarters of all orders, which Trahan said weakens supporters’ argument that a red flag law would help reduce suicides.

“Our law is working. There’s no way they can spin that any other way,” he said.

Some supporters of a red flag law, like Sorensen, said that Maine shouldn’t have a law that conflates mental illness with violence. A person could be violent without an underlying mental illness, and mental illness does not necessarily predispose someone to commit a violent act, which is part of why supporters want to do away with the behavioral health assessment requirement.

But Trahan sees it differently. To him and other opponents, getting rid of the assessment — and giving people who are not law enforcement officials the power to directly petition the court to remove someone’s weapons — suggests the aim of the red flag law is “eliminating due process in the law.”

“This is a slippery slope,” he said. “Because if you can do it for a person’s Second Amendment, you can do it for a person’s First Amendment, Fourth Amendment, Fifth, 14th, you name it.”

Trahan said there are already other ways to take away weapons from a person who poses a threat of violence, like protection from abuse orders or arresting someone on criminal threatening charges.

Other opponents of the red flag law include the Maine State Police — with Lt. Michael Johnston writing in testimony earlier this year that the agency worries it could increase the likelihood of a violent encounter — and Gov. Janet Mills. The Democrat was part of the bipartisan group who helped draft the yellow flag law in 2019.

In an op-ed published in the Portland Press Herald, Mills said a red flag law would “create a new, separate and confusing process that will undermine the effectiveness of the law and endanger public safety along with it,” adding that based on her experience, “if there is a potentially dangerous situation, I want the police involved as soon as possible.”

The Maine GOP also opposes the proposal.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit civic news organization. To get regular coverage from The Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.