Enthusiasm for birding, nature-watching increases, as pandemic surges

A yellow throated warbler spotted by Kristen Lindquist on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

A yellow throated warbler spotted by Kristen Lindquist on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

Don Reimer. (Courtesy Don Reimer)

Don Reimer. (Courtesy Don Reimer)

Kristen Lindquist birding on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding in South Carolina. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding in South Carolina. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Tom Aversa. (Courtesy Tom Avera)

Tom Aversa. (Courtesy Tom Avera)

Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

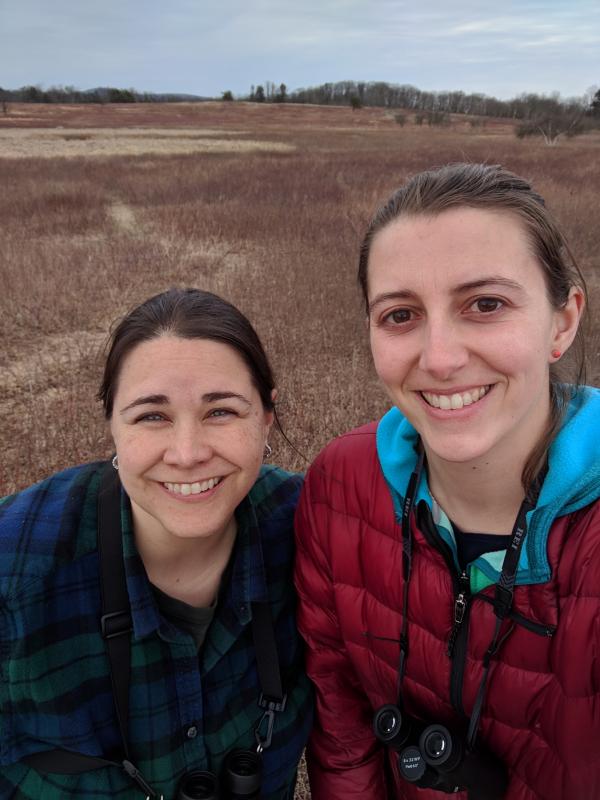

Steph Phenix, left, and Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

Steph Phenix, left, and Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

A pair of brant geese spotted by Kristen Lindquist in Scarborough. (Courtesy photo)

A pair of brant geese spotted by Kristen Lindquist in Scarborough. (Courtesy photo)

A snow bunting on Clarry Hill in Union spotted by Kristen Lindquist. (Courtesy photo)

A snow bunting on Clarry Hill in Union spotted by Kristen Lindquist. (Courtesy photo)

A yellow throated warbler spotted by Kristen Lindquist on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

A yellow throated warbler spotted by Kristen Lindquist on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

Don Reimer. (Courtesy Don Reimer)

Don Reimer. (Courtesy Don Reimer)

Kristen Lindquist birding on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding on Monhegan Island. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding in South Carolina. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Kristen Lindquist birding in South Carolina. (Courtesy Paul Doiron)

Tom Aversa. (Courtesy Tom Avera)

Tom Aversa. (Courtesy Tom Avera)

Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

Steph Phenix, left, and Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

Steph Phenix, left, and Kate Doiron. (Courtesy Kate Doiron)

A pair of brant geese spotted by Kristen Lindquist in Scarborough. (Courtesy photo)

A pair of brant geese spotted by Kristen Lindquist in Scarborough. (Courtesy photo)

A snow bunting on Clarry Hill in Union spotted by Kristen Lindquist. (Courtesy photo)

A snow bunting on Clarry Hill in Union spotted by Kristen Lindquist. (Courtesy photo)

MIDCOAST — As COVID-19 closed in last March, and as snow thawed while winter turned to spring, interest in birdwatching — actually, the more formal word is birding — rose throughout the Midcoast. Enthusiasts took to the outdoors, away from each other and toward the natural landscape to clear the mind of the pandemic’s uncertainty.

Downloads of popular bird identification apps significantly rose, according to the Associated Press, which noted preliminary numbers indicating sales of bird feeders, nesting boxes and birdseed also had jumped.

“Downloads of the National Audubon Society's bird identification app in March and April doubled over that period last year, and unique visits to its website are up by a half-million,” reported the AP. “The prestigious Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York, has seen downloads of its free bird identification app, Merlin ID, shoot up 102% over the same time last year, with 8,500 downloads on Easter weekend alone.”

The trending rise of interest in birding continued in the Midcoast.

“I’ve certainly noticed an increase in interest in birds and birding now that all of us are spending a lot more time stuck in our own homes and backyards,” said Kristen Lindquist, a Camden resident, writer and poet, and avid observer of the natural world.

Birding often a family legacy

Another longtime birder, Don Reimer of Warren gained an interest in birds during his years of early adolescence watching the birds descend upon his family’s bird feeders at his New Harbor childhood home.

“My mother's interest in birds and wildlife was a great boon,” he said. “Seasonal arrivals, such as winter pine siskins and common redpolls, were especially appealing. My interest in birds continued to grow from those early times.”

Though Reimer has no single favorite species, he noted there is an excitement to observe the occasional “out-of-range” species, such as mew gull, ruff sandpiper, black-headed grosbeak, and great gray owls.

The one species that has become a personal elusive nemesis for Reimer is the Connecticut warbler, a species that passes through Maine in limited numbers in fall.

New opportunities for fresh bird encounters brought forth by each sunrise excites Reimer, who has spotted 191 birds this year.

“Stepping out the door, one never knows what unexpected species we may encounter or what unique bird behavior we may witness,” Reimer said. “Sharing bird sightings with others is an added bonus experience for many birders, and a way to increase each other's knowledge and experiences with birds.”

Weather conditions limiting ability to see or hear birds is the most challenging aspect of birding, Reimer noted.

“Windy conditions obscure bird sounds, but can prove advantageous for seeing ocean birds,” he said. “Frigid weather and snow cover can restrict access to birds, as well.”

Dreaming about birds

Lindquist discovered her passion for birding at a young age while on her grandparents’ Lincolnville farm. There, the landscape was dotted with feeders that welcomed hummingbirds, which zipped around her all summer. It was an experience that never got old.

“They had such personality and were such dazzling jewels, so tiny and fast and fierce,” she said.

At age 12, Lindquist identified an Indigo Bunting using a Peterson Field Guide to the Birds.

“I remember that bright, unreal blue of the bird, and the satisfaction of finding its match in the bird book,” she said. “Just flipping through the pages was so thrilling — to imagine all those beautiful creatures out there somewhere! That’s when I began to dream about birds.”

Lindquist began to keep a checklist of birds she spotted wherever she went, and has become more involved with birding since her move nearly three decades ago back to Maine after graduate school.

She joined Maine Audubon field trips and various other outings with seasoned birders and participates yearly in the local Christmas Bird Counts, which provides, “valuable insight into bird populations and the health of their habitats, helping wildlife organizations implement conservation strategies.”

“It seems like the more I’ve learned about birds, the more fascinating they are to me,” Lindquist said. “And, there's still so much to learn, and so many birds I haven't yet seen.”

Lindquist is captivated by unexpectedly finding birds that should not be in the area at a given time of year, or which are rare finds.

“It’s really a form of meditation, in a way, because you have to open yourself up, to observe and listen to what’s around you, developing a heightened awareness of your surroundings that takes your mind off whatever your petty personal concerns and anxieties are at the moment,” she said. “Birds are all around us, and especially during migration, you never know what might wander through your yard or along your favorite hiking trail.”

Birding is likewise a mind expanding activity.

“Birding is an opportunity to experience the landscape and its wildlife at ground level, while you wander around and stare at the trees and the sky hoping to see or hear birds,” said Lindquist. “It is a great way to get to become familiar with a new landscape — my husband and I love birding in southwest Arizona, for example, or when we're on vacation on the Gulf Coast of Florida.”

And, it takes concentration.

“The most challenging part of birding is that birds have wings, so they can be anywhere they want to be, which is not always right in front of you and your binoculars,” said Lindquist. “If you get into birding, you have to learn how to let things go — you aren't going to be able to [identify] everything. Sometimes you'll just never know what that intriguing bird was.”

Lindquist has a plethora of favorite birds, including the Cedar Waxwing (described by her as a beautiful bird that hangs out in gregarious flocks that share berries with one another) and its bigger, paler cousin, the Bohemian Waxwing, which comes south into Maine some winters to feast on berries and crabapples.

With approximately 30 species of warblers around Maine, she considers the quest to find them, depending on the season, a fun challenge, particularly during spring and fall migration.

“Birders from around the world come to Maine to see warblers; we're so lucky here in that way,” she said.

Owls, described by Lindquist as charismatic and mysterious, and sparrows, whose nuances of their plumages, body shapes, and songs can be as satisfying as solving a puzzle, also top the list of Lindquist’s favorites.

Never ending source of enjoyment

Spotting an unexpected bird, either one not generally found in the area that time of year or a rare find for the area, is what excites Tom Aversa of Unity the most about the activity.

Aversa is also quick to note finding enough time to participate in birding is his biggest challenge, though he has recorded 240 birds this year.

“The natural world is a never ending source of enjoyment,” he said. “Birds are the easiest vertebrates to observe wherever you might happen to find yourself.”

Aversa noted it is difficult to select one favorite bird, but Winter Wrens, common and full of personality, are among his favorites, as is the Golden-winged Warbler, rare and declining.

A ‘big year’ challenge

Early on in the pandemic, Kate Doiron challenged her friend, Steph Phenix, of Arkansas, to a big year challenge to see who could spot the most species of birds in a single year when they realized in March they would be unable to get together due to the pandemic.

“Birding was a way to get outside every day, find new beautiful places to visit, and maybe read the news a little less,” said Doiron, who gleaned a passion for birding as a child from her grandfather and comes from a family keen on birding. “And it's a very pandemic-safe hobby. Little did we know how much we would get into it. We both bought spotting scopes this year and made lots of local birding friends along the way who are all cheering us on.”

Poised to conclude the challenge Dec. 31, both women have recorded 218 birds each, as of Dec. 14. With each day of the challenge ticking by, spotting new additions has become tougher and has required each to hit the road to expand their efforts.

“We saw all of the ‘easy’ birds a long time ago, and we are having to go further from home to more random locations to get new ones for our year lists,” noted Doiron.

In fact, Doiron recently drove to Ogunquit to see the famous Rock Wren, which, she noted, is uncommon and only the second time one has ever been seen in Maine, while Phenix trekked from her Arkansas home to coastal Louisiana twice this year to tally coastal birds and roseate spoonbills.

To Doiron, the most exciting aspect of birding is finally spotting an elusive bird — formally known as spotting a lifer when you get a new bird for your life list — you have been trying to spot for a long time. This year, Doiron has tallied an impressive 44 lifers while Phenix has recorded 69.

Doiron’s favorite bird to find this year, which was a beautiful lifer, was a razorbill out at Eastern Egg Rock, hanging out with the puffins. Phenix, meanwhile, is most proud of spotting a fork-tailed flycatcher, a South American bird that drew birders from all over Arkansas.

Topping the 2020 list of birds Doiron has yet to spot is an evening grosbeak, a bird Doiron is pretty hopeful to spot as she noted many people have seen them at their feeders this year.

Healthy therapy

“Birds are declining all around the world, precipitously in many cases,” said Aversa. “If you enjoy the forests, fields and other natural habitats support elected officials that care about conserving our natural resources.”

Financially, bird conservation can be supported by donating to Maine Audubon, the National Audubon Society, and the American Bird Conservancy.

Bird feeders and bird houses are other ways to support conversation efforts.

“Always buy good quality seed and keep your feeders, and underneath the feeders, clean so they don’t attract rodents or harbor diseases that can harm the birds,” said Lindquist. “I see feeders as the least we can do to help counteract our windows, cats, cars, and habitat destruction.”

You can also plant your yard with native species that will attract birds and landscape for their benefit, Lindquist advised, noting crabapple trees, viburnums, and other berry bushes will attract winter flocks. Any kind of water feature, even a little bird bath, will bring them in, she noted.

“Getting to know the local birds is a way to know a place more deeply,” said Lindquist. “The landscape suddenly takes on more meaning — that crabapple in your neighborhood will never look the same since the day you saw a flock of Pine Grosbeaks eating all the fruits; you'll always look up at that tree at Merryspring where a Barred Owl was perched one afternoon, remembering; you'll never be able to drive by a marsh without looking for another Red-winged Blackbird or Great Blue Heron.”

Birding amid the pandemic is a wonderful way to stay connected to the natural world, and also stay sane amid these troubling days, which is why it is important to assist in conservation efforts.

“For many of us, birds are the wildlife we see the most, so they become our primary link to the natural world,” said Lindquist. “And making connections with the natural world will ground us and help us stay sane and healthy in these trying times. And hopefully a growing familiarity with birds will also lead you to care about them on a broader level, to support wildlife conservation and habitat protection efforts, to perpetuate the joy.

“Because while numbers of bird-watchers are going up, the numbers of our birds are going way down, thanks to the severe gauntlet they face of habitat loss, pesticide use, cats, window strikes, etc. So the more people who are interested in and care about birds, the better that bodes for the future of birds.”

“Bird watching and feeding birds is now one of the most popular pastimes in America,” Reimer said. “I have seen expanded public awareness and interest in birds in recent months, as folks spend more time at home. Being out in nature is an inexpensive and healthy therapy for all of us in these challenging days.”

Event Date

Address

United States