Belfast, Camden students create change an ocean away

Liberian Education Fund founder Kim Ouillette with students in Liberia.

Liberian Education Fund founder Kim Ouillette with students in Liberia.

The Belfast Area High School chapter of the Liberian Education Fund. (Photo Zachary Smith)

The Belfast Area High School chapter of the Liberian Education Fund. (Photo Zachary Smith)

Camden Hills Regional High School’s LEF chapter.

Camden Hills Regional High School’s LEF chapter.

Members of Watershed High School’s LEF chapter gather material for a wreath sale.

Members of Watershed High School’s LEF chapter gather material for a wreath sale.

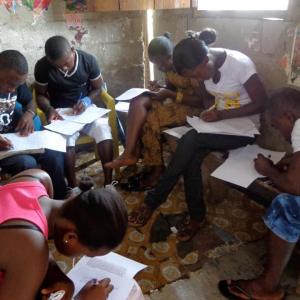

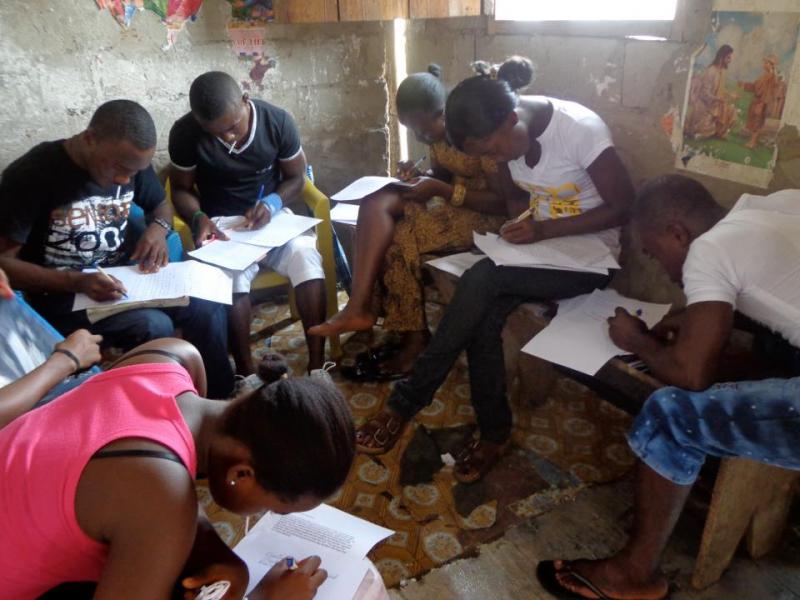

LEF students writing letters to students in Maine. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF students writing letters to students in Maine. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF student Lucia Tamba on her graduation day. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF student Lucia Tamba on her graduation day. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, with LEF student Romeo Quoi. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, with LEF student Romeo Quoi. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

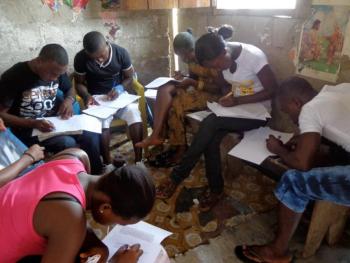

Teloe Moore, right, leading a meeting for LEF students at his home. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, leading a meeting for LEF students at his home. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

From left: Teloe, Kim, and LEF student Felicia in Buchanan, Liberia.

From left: Teloe, Kim, and LEF student Felicia in Buchanan, Liberia.

Liberian Education Fund founder Kim Ouillette with students in Liberia.

Liberian Education Fund founder Kim Ouillette with students in Liberia.

The Belfast Area High School chapter of the Liberian Education Fund. (Photo Zachary Smith)

The Belfast Area High School chapter of the Liberian Education Fund. (Photo Zachary Smith)

Camden Hills Regional High School’s LEF chapter.

Camden Hills Regional High School’s LEF chapter.

Members of Watershed High School’s LEF chapter gather material for a wreath sale.

Members of Watershed High School’s LEF chapter gather material for a wreath sale.

LEF students writing letters to students in Maine. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF students writing letters to students in Maine. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF student Lucia Tamba on her graduation day. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

LEF student Lucia Tamba on her graduation day. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, with LEF student Romeo Quoi. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, with LEF student Romeo Quoi. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, leading a meeting for LEF students at his home. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

Teloe Moore, right, leading a meeting for LEF students at his home. (Photo Kim Ouillette)

From left: Teloe, Kim, and LEF student Felicia in Buchanan, Liberia.

From left: Teloe, Kim, and LEF student Felicia in Buchanan, Liberia.

Belfast—Teloe Moore arrived in Belfast in late December. I met him on New Year’s Eve at the bonfire by the public landing. It was a frigid night, and even under a heavy coat, scarf, hat and gloves, he was shivering. One can hardly blame him: Born and raised in Liberia, he had never experienced temperatures below 70 degrees.

Moore was able to attend high school in his home country because of a scholarship from the Liberian Education Fund — a student-run nonprofit organization founded in 2007 by Kim Ouillette, then a sophomore at Belfast Area High School.

Ouillette became interested in Liberia when she read a letter written by Stan Stalla, of Northport. Stalla was working for the U.S. Agency for International Development — responsible for delivering aid to foreign countries — and related his experiences abroad in emails to friends and family in Maine. While in Liberia he wrote about a little girl named Viola:

“Viola’s story is like the sad story of so many kids throughout this continent: no father, too many siblings, lives with grandmother, no money to pay the school fees.”

Ouillette wanted to help kids like Viola, so she organized a group of friends and began fundraising. Stalla put her in contact with Joe Hoover Gbadyu, a Liberian who had spent most of his life working for NGOs in Liberia, many of them related to education.

“That January [2007] we sent our first student to school. In September, we had raised enough money to sponsor 12 students,” Ouillette told me recently.

The average cost for one year high school in Liberia is $250.

Moore was one of the first students to receive an LEF scholarship. He is now a regional LEF coordinator in Monrovia, Liberia’s capital city. As a coordinator, he seeks out scholarship candidates, reviews applications and provides support to the LEF students that he is responsible for.

“I want to build the group,” he says. “They are my children.”

Moore helps students work out problems with their teachers, hosts monthly meetings at his house, and always attends his students’ graduations. When one of his students fell suddenly ill and died last fall, Moore and his students provided emotional support to the family.

Ouillette has long dreamed of bringing an LEF student to the US. While working in Liberia this fall for The Carter Center, Ouillette helped Moore secure an American visa.

“When I got off the plane [in Maine], I felt cold. I felt very cold,” Moore remembers.

Moore and Ouillette visited the LEF chapters at Belfast Area High School, Camden Hills Regional High School and The Watershed School. Moore also spoke at the Belfast Rotary.

One evening during his stay, Moore shared his story with the community at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Belfast. He is soft-spoken yet deliberate in his speech. During the presentation he spoke comfortably. Accompanying photographs were projected on a screen behind him.

“My mother had never sat in a classroom,” he said. “My father was a high school dropout.”

Moore is the eleventh of thirteen children. He attended school until the fourth grade. Then his mother passed away, and he left school.

“As a child, you don’t understand that education is important,” he said. “Mainly children just roamed around the streets, doing nothing.”

He attended junior high school on a soccer scholarship, but his education was disrupted by Liberia’s civil war.

In the slideshow, he flipped to a photograph of a bullet-raked shell of a car sitting on bricks in front of a wall riddled with pockmarks. The next picture showed a group of wiry kids riding in the back of a pickup truck, clutching AK-47s.

“Child soldiers were more dangerous than adult soldiers,” he said. “They were so brave that they didn’t care about anything.”

Some of Moore’s childhood friends fought in the war.

“Sometimes [the army] would drive around the neighborhood in black pickup trucks, taking kids off the street and making them join the army,” he said. “We’d have to hide. One time, my dad made us all stay inside for a week.”

Because of the violence all around them, children grew up believing that “the only solution was violence,” he said.

Even after the war, Moore had no money to go to high school. Then he met Joe Hoover Gdadyu through his church’s soccer team.

Gdadyu spoke with Moore and decided to award him one of LEF’s first scholarships.

“It came at just the right time,” Moore told the small crowd gathered in the UU Church.

Moore’s high school education opened doors to him. Today he is studying computer science at a vocational school in Monrovia in addition to his work as an LEF coordinator. He recently applied for a scholarship to attend the University of Maine at Orono, where he hopes to study resource management and environmental policy.

“Liberia has so many natural resources,” he says, referring to the oil, rubber, cocoa, coffee, sugarcane, timber, and diamonds that account for much of Liberia’s exports. Moore continues: “But the money from [these resources] leaves the country. I want to help Liberia benefit from its resources and make jobs for the youth.”

For those of us involved with LEF in Belfast, Moore’s visit provided an occasion to take stock of the progress the group has made over the past seven years.

In its first year the Liberian Education Fund sent one student to school. Today the organization is sponsoring over 32 students in high school and college. New chapters have opened in Camden — at Camden Hills Regional High School and the Watershed School — and also outside of Maine at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and Boston University. Together the chapters have raised thousands of dollars to send over fifty students to school.

“Whenever I come home, I am so happy to see how much it’s grown,” Ouillette says.

This year I became the communications director for the Belfast LEF branch. I work with president Romy Carpenter, vice-president Kyah Watson-Fontaine, secretary Emma Moesswilde, treasurer Lacey Durkee and the 25 members to organize fundraisers and spread awareness in the community.

The LEF members in Belfast and Camden work year-round, raising thousands of dollars through raffles, concerts, school dances, cake sales, wreath sales, bake sales, and more in order to send a comparable number of our peers across the Atlantic to high school.

Even though we exchange letters with students in Liberia, it can sometimes be difficult to understand how selling raffle tickets door-to-door in Belfast impacts the high school education of students in Liberia.

Moore gave us that connection. He showed us that LEF’s efforts — both in Maine and Liberia — are making a difference in students’ lives.

“Teloe made the whole experience of participating in LEF seem real,” says Sam Cloyd, vice-president of Camden High School’s LEF.

Louisa Crane, co-president of LEF’s Watershed chapter, says that meeting Moore helped her and her friends connect more personally to LEF’s work.

Romy Carpenter, Belfast LEF’s president, adds that “Hearing Teloe’s story puts perspective on our lives. We have it pretty good here.”

Will Mossing, a member of the Belfast chapter, said it best when he told Moore what his visit meant to us:

“It helps us put a face on the people we are helping.”

LEF as a whole is evolving and growing. The increase in high school scholarships in Liberia means more graduates, many of whom will seek a college education.

Some who have already gone on to college have founded LEF branches there. The U.S. chapters at George Washington University and Boston University are sponsoring seven university students in Liberia. A college education in Liberia costs roughly $600 dollars a year.

The expansion of the organization has created new needs and challenges. LEF is officially registered as a nonprofit organization in both Liberia and the U.S., but has no office on either side of the Atlantic.

“I keep all the applications, financial records, grades and other paperwork in a suitcase in my house,” says Moore.

He and Ouillette are looking into renting an office for LEF in Monrovia

“If we are to be a real organization, we need an address so we can be contacted easily. I want to get a computer so students can print documents, learn to type, and use Facebook to communicate with [students] in the U.S,” he said.

In Belfast, membership continues to rise as LEF becomes better known in the community. Our friends in the Camden and Watershed branches are likewise building their community presence. There are now five LEF chapters and interest in starting more. In seven years, we’ve gone from sponsoring one student to sponsoring 32.

Still, says Ouillette, “There are so many students that want to go to school.”

To learn more about the Liberian Education Fund, please visit us online at liberianeducationfund.com.

Event Date

Address

United States