Mainers are crying out for comprehensive tax reform: Will our legislators listen?

Warning sirens are ringing and red lights are flashing across the state. Counties are proposing unusually large budget increases, many in the double digits. At the same time, voters in multiple communities are voting down school budgets, often more than once.

Municipal budget committees are becoming increasingly angsty. These developments are often treated as separate stories. They are not. Together, they point to a deeper structural problem in how Maine funds public services, and ultimately the need for comprehensive tax reform.

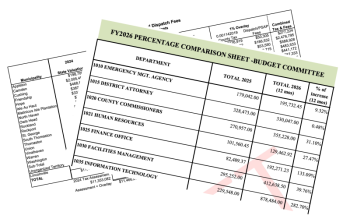

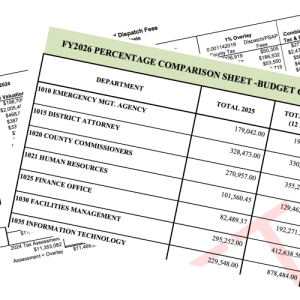

This year, counties such as Penobscot, Knox, York, Washington, and now Waldo, are seeing sharp cost increases driven largely by jails, public safety systems, facilities, staffing shortages, insurance, and inflation.

Penobscot County has publicly acknowledged a major shortfall tied to jail costs. Knox County towns are absorbing a county budget increase approaching 14 percent. Washington County is confronting the consequences of years of deferred decisions, while York County’s operating and personnel costs continue to climb.

At the same time, voters across Maine have rejected school budgets in districts large and small — even where costs are driven by special education, transportation, workforce shortages, and inflation that local communities do not control.

From a household’s perspective, these are not separate policy debates. Municipal taxes, county assessments, and school budgets arrive as one combined tax bill. When all three rise at once (even for understandable reasons) families hit a limit. Voting down school and municipal budgets are often the first and most visible ways voters signal that they cannot absorb more.

This is not a rejection of education, public safety, or local government. It is a warning: Maine relies too heavily on a single revenue source - the property tax.

In Maine, property taxes fund local roads and fire departments, schools, and also services largely dictated by state policy decisions — county jails, courts, prosecution, schools, emergency communications, and compliance with state mandates. When costs rise across all of these systems at once (wages, health insurance, utilities, construction, and jail medical care) the property tax is left carrying the entire burden.

Counties have particularly few options. They rely almost entirely on assessments to municipalities and cannot diversify revenue. When pressure builds, the result is not gradual adjustment, but sudden tax spikes — exactly what we are seeing now.

Federal pandemic relief postponed this reckoning but did not solve it. One-time funding allowed governments to avoid tax increases and invest in needed facilities and systems. That money is now ending. Inflation is not. Many costs created or deferred during those years are permanent. What seems sudden today is the inevitable result of costs that were deferred over several years.

The Legislature should take this as a clear signal that comprehensive tax reform is needed — not later, but now.

That means shifting a greater share of clearly state-driven costs, particularly county jails and other court-related functions, to stable state funding sources. These are not local policy choices, yet they are funded largely through local property taxes.

It also means strengthening and stabilizing state education funding so school budgets are not constantly squeezed by rising municipal and county costs, making local budget votes harder to sustain.

And it means modernizing Maine’s revenue mix so statewide economic growth contributes more directly to funding statewide responsibilities. The property tax, which does not reflect ability to pay and responds poorly to economic change, cannot continue doing this work alone.

Counties and school districts from Washington County to Knox County, from Penobscot to York, are delivering the same message at the same time. This is not simply a crisis caused by waste or bad management. It is a system that has drifted out of alignment with economic reality, which no amount of municipal, school district, or county belt tightening will fix it.

If the state paid for state programs and left the property alone to serve local programs and initiatives the tax would be properly reactive to needs of municipalities and their citizens.

The warning lights are flashing. The Legislature should act now to realign responsibilities with funding — not after more budgets fail, but before the system of funding basic public services totally breaks down.

Audra Caler is the Camden Town Manager and lives in Camden