Kristen Lindquist: On Millay and Mount Battie

View from the mountaintop. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

View from the mountaintop. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) The three islands depicted in “Renascence,” from left: Lasell, Saddle, and Mark islands. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

The three islands depicted in “Renascence,” from left: Lasell, Saddle, and Mark islands. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) Two of the three “long mountains” from “Renascence,” from left: Ragged (now featuring the Snow Bowl) and Bald, taken from the Mt. Battie tower. The third is Megunticook, out of the frame from this angle. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

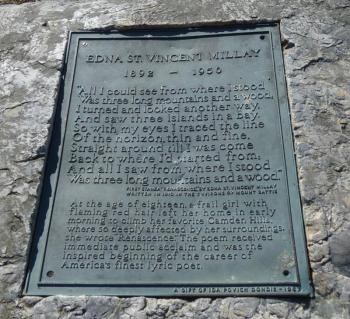

Two of the three “long mountains” from “Renascence,” from left: Ragged (now featuring the Snow Bowl) and Bald, taken from the Mt. Battie tower. The third is Megunticook, out of the frame from this angle. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) The plaque honoring Millay at the summit of Mt. Battie. (She actually finished “Renascence” in 1911.) (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

The plaque honoring Millay at the summit of Mt. Battie. (She actually finished “Renascence” in 1911.) (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) Post-Renascence Edna St. Vincent Millay, when she was a student at Vassar College. Millay1914 (Arnold Genthe; Public Domain)

Post-Renascence Edna St. Vincent Millay, when she was a student at Vassar College. Millay1914 (Arnold Genthe; Public Domain) View from the mountaintop. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

View from the mountaintop. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) The three islands depicted in “Renascence,” from left: Lasell, Saddle, and Mark islands. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

The three islands depicted in “Renascence,” from left: Lasell, Saddle, and Mark islands. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) Two of the three “long mountains” from “Renascence,” from left: Ragged (now featuring the Snow Bowl) and Bald, taken from the Mt. Battie tower. The third is Megunticook, out of the frame from this angle. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

Two of the three “long mountains” from “Renascence,” from left: Ragged (now featuring the Snow Bowl) and Bald, taken from the Mt. Battie tower. The third is Megunticook, out of the frame from this angle. (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) The plaque honoring Millay at the summit of Mt. Battie. (She actually finished “Renascence” in 1911.) (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist)

The plaque honoring Millay at the summit of Mt. Battie. (She actually finished “Renascence” in 1911.) (Photo courtesy Kristen Lindquist) Post-Renascence Edna St. Vincent Millay, when she was a student at Vassar College. Millay1914 (Arnold Genthe; Public Domain)

Post-Renascence Edna St. Vincent Millay, when she was a student at Vassar College. Millay1914 (Arnold Genthe; Public Domain)In honor of Maine’s 200th anniversary as a state this month, I offer up something a little different than my usual natural history, mixing it up a bit with Maine’s literary history.

In February I participated in a poetry reading to mark the 128th birthday of local poet turned star Edna St. Vincent Millay. A few days later, I hiked up Mt. Battie. It occurred to me that a simple walk up this local landmark serves as a literary pilgrimage of sorts, to honor this famous daughter of Maine. At the summit, in front of the stone tower (a WW I memorial), you might notice a simple plaque engraved with the opening lines of Millay’s lyrical poem “Renascence”:

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way,

And saw three islands in a bay.

Millay was a teenager living in Camden when she wrote that poem, which clearly describes the view from Mt. Battie, one of her habitual walks.

Her “three long mountains,” counted with her back to the water as she hiked up, were Megunticook, Bald, and Ragged mountains. These mountains are most easily visible now from the tower, which didn’t yet exist at the time she wrote the poem. (Instead, she would have found at the top the Summit House, a fixture from 1898 - 1920.) She took some poetic license with the bay view, as many more islands punctuate Penobscot Bay. But Mark, Saddle, and Lasell islands stand out distinctly as the right-most, nearest three.

Likewise, her poem “Afternoon on a Hill” feels to me like it was written from the slopes of Mt. Battie. In the poem she describes touching “a hundred flowers” without picking one and looking “with quiet eyes” at “cliffs and clouds.” In the final stanza, it’s dusk and “the lights begin to show/up from the town,” so she finds her house and “start[s] down.” What resident of Camden at the top of Mount Battie hasn’t tried to pick out their own house down below? The various houses in which Millay, her mother, and her sisters lived around town, on Washington and Chestnut streets, would each have been readily visible.

Published in the Lyric Year’s anthology in 1912, “Renascence” introduced Millay’s name to the literary world. In that same year, she recited her poem at a staff party at the Whitehall Inn, where her sister worked. She caught the attention of one of the inn’s wealthy guests, who soon arranged for Millay to attend Vassar.

After college, she moved to Greenwich Village, published her first book of poetry in 1917 (Renascence and Other Poems), and fully lived the life of a poet. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1923, the first woman poet to do so, and became a rock-star of a poet; thousands of people flocked to her readings.

While I am very grateful that “Renascence” helped launch Millay into the world as a young poet, I’ve never been fond of the poem. If you read past those place-setting opening lines, it gets weird and melodramatic: She imagines herself lying down on the rocks to look up at the sky, to suddenly become one with the world. She feels everyone’s pain, upon which she’s buried alive, to be finally, transcendently reborn, raising her “quivering arms on high” and laughing.

That’s not my typical Mt. Battie experience, although I do sometimes find transcendence there, and even poetic inspiration. I try to find a spot off on my own—Camden Hills State Park is, for good reason, one of the state’s most visited parks—where I can appreciate the spectacular view of the bay and the Camden Hills without disturbance. I’m struck over and over by the blue of the bay, the islands strung like jewels along its length, and the quality of the sky when you can see so much of it—as Millay must have when she lay down on those open ledges along the trail.

I notice the curves and contours of the surrounding mountains, their bare patches, cliffs, lines of spruces. Sometimes a hawk soars past, or one of the resident ravens will check me out, commenting on my presence with a loud quork. This is where I go to literally rise above the worries of the world in a matter of a few minutes’ walk; I do not imagine myself six feet underground. But Millay’s ability to go there was an indication of her brilliant poetic mind even at that young age. She knew what she was doing, and it was, in part, this confidence that drew the attention of her future benefactor at the Whitehall Inn.

You can make your own Millay pilgrimage: Pocket a copy of one of Millay’s poems: “Afternoon on a Hill” or “Ragged Island” or one of her many sonnets. Hike up the Mt. Battie trail, as she once did; a pilgrimage requires that you sweat a little. At the top, take in the view, really appreciating it, from the glimpse of Monhegan beyond the cement plant to the west, to the rising contours of Isle au Haut, Acadia, and the little knob of Blue Hill to the east, with all the islands of Penobscot Bay in-between. Let your eyes rest on each hill or each island as visual touchstones. Ground yourself in this place.

Now find a spot to sit on a patch of rock that’s been scraped bare by the glacier. Read aloud the poem you brought and imagine Millay herself in that very spot, a brilliant young woman good with words but dirt-poor. She’s looking down at all she knows of the world. And something about the embracing mountains and the blue bay stretching to the horizon inspires her soul, sparks a poem. Something about this rugged place where the mountains so beautifully meet the sea helps launch her career making poetry about the landscape of the heart.

Kristen Lindquist is an amateur naturalist and published poet who lives in her hometown of Camden.

Event Date

Address

United States