Kristen Lindquist: Planet Jupiter, near and bright on a summer's night

While we were driving home to the Midcoast from an event in central Maine recently, just past sunset, fields of lush green grass glowed on either side of the car. As the passenger, I kept watch for whatever might appear on such a verdant stage: a deer or porcupine, perhaps, or maybe the twinkling of some early fireflies.

What I saw instead: a herd of Holsteins with two calves playfully butting heads, the most fluorescent pink azalea I've ever seen, the first patch of blue lupine in full bloom. And a steady, shining light, low in a sky still too bright for stars—the planet Jupiter.

"We're going to follow Jupiter home," my husband said.

And the small orb really did seem to hover ahead of us above the road for most of our drive. As we pulled into our driveway, it hung above our street like a homing beacon, more vivid than the dot representing our car on the Google Maps route that had guided us home.

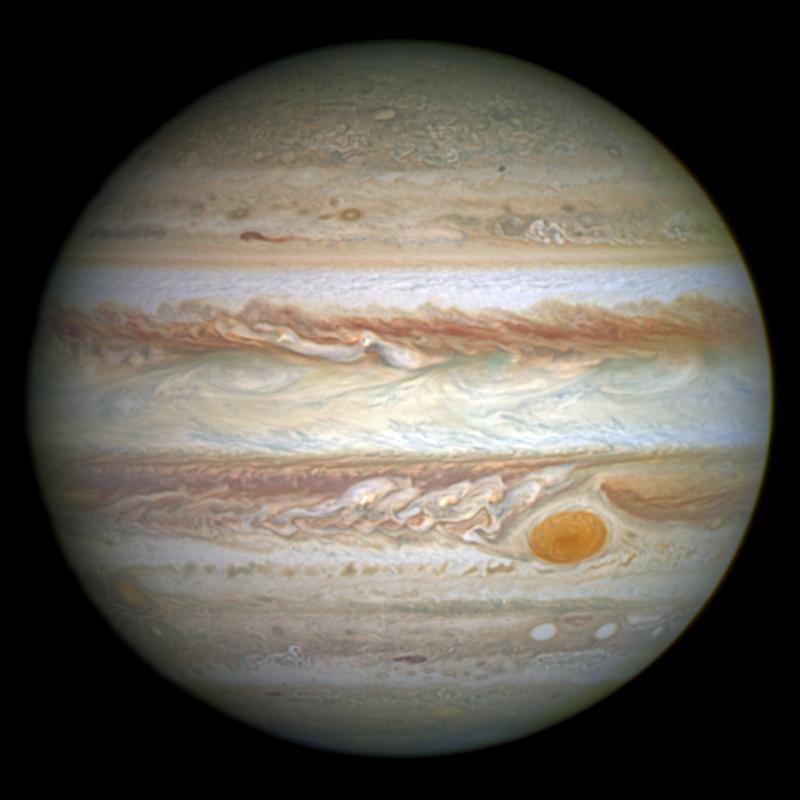

The largest planet, named for the Roman sky god, the king of the gods, reigns brightly in the night sky this month. Visible from dusk to dawn, Jupiter can be found at sunset already rising in the eastern sky, and sets in the west at around sunrise. For most of the summer, Jupiter will be hanging out near Antares, a red giant in the constellation Scorpius also known as the Heart of the Scorpion.

Mid-June, Jupiter is at its closest point to Earth, which helps explain the planet's magnitude of brightness. According to EarthSky.org, Jupiter is currently 14 times brighter than the planet Saturn, which rises a few hours later than Jupiter each night. So you probably won't mistake one for the other.

Jupiter's yearly opposition with Earth—the point at which the Sun, Earth, and Jupiter are in direct alignment—happened on June 10 this year. Because the orbits of both the Earth and Jupiter are elliptical, however, the two planets are not their at their closest, or perigee, during opposition. Perigee happened a couple days later on June 12.

Even if you missed Jupiter's opposition or perigee, the giant planet will continue to be very visible all night long through much of the summer, offering up an astronomical spectacle worth taking a look at. With good binoculars, on a clear night you should be able to see all four Galilean moons, so named because they were first spotted by the Italian astronomer Galileo in the early 1600s.

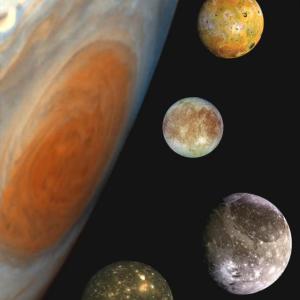

Galileo referred to these Jovian moons at the time as the Medician Stars, naming them as a group for four brothers of the Medici family from which he sought patronage. He labeled them I, II, III, and IV. This naming system became less practical, however, as more and more moons of Jupiter were discovered.

Simon Marius, a German astronomer who independently noted the four moons' existence at about the same time as Galileo, chose their names from Greek mythology: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

All four were lovers of Zeus, the Greek form of Jupiter; Io, Europa, and Callisto were mortal women seduced by Zeus in various guises.

Ganymede was a young man that Zeus, in the form of an eagle, carried off to become the gods' immortal cup-bearer.

Both Callisto and Ganymede are additionally represented in the night sky as the constellations Ursa Major (the Great Bear) and Aquarius (the Water Carrier) respectively. So whatever his initial promises to them were, lover boy Zeus really did give them the moon and stars, in his way.

The four satellites are the largest of Jupiter's 79 moons. (Jupiter has the most moons of any planet.) They are also some of the biggest bodies in our solar system. Ganymede, the largest moon of our largest planet, is actually bigger than Mercury or Pluto and would be a planet in its own right if it were orbiting the Sun instead of Jupiter.

Seen with good binoculars, the Galilean moons look like tiny stars arrayed on either side of Jupiter, on the same plane. Sky & Telescope offers an online tool you can use to look up which moon is which in your current view, by date and time.

When you see them for yourself, try to imagine how revelatory it must have been for Galileo, later called "the father of observational astronomy," to see for the first time heavenly bodies that were clearly not orbiting Earth.

This was a significant realization at a time when our planet was thought to be the center of the universe. And it may have been one of the sparks that helped lead Galileo to the then-heretical idea of a heliocentric system. Galileo would spend the end of his life under house arrest for expressing a belief that Earth revolves around the Sun and not vice versa, as the Church espoused.

The planets and moons themselves can serve as perfect touchstones for brushing up on ancient Greek and Roman mythology, as well. All of the planets in our solar system and most of their moons have names from classical mythology, after all. I can think of worse ways to while away the summer days then re-reading these old stories.

Or the simple beauty of bright Jupiter rising amid a backdrop of stars, as fireflies shift and twinkle in the fields below like tiny stars brought down to earth, may be captivating enough in itself on a summer's evening.

Kristen Lindquist is an amateur naturalist and published poet who lives in her hometown of Camden.

Event Date

Address

United States