Future of Maine’s electric vehicle charging network in limbo as federal changes loom

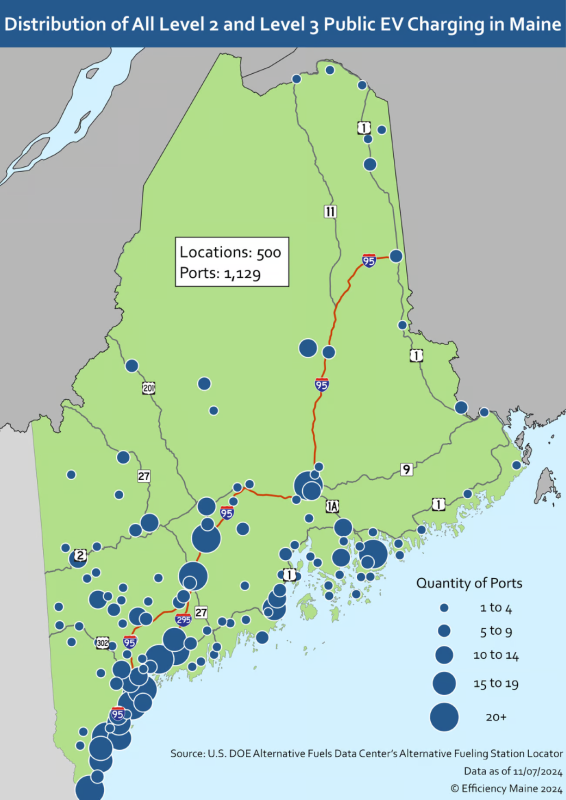

If you’re driving an electric vehicle up I-95 or 295 these days, particularly in York or Cumberland counties, odds are you won’t have to travel far before hitting a public charging station.

But head north and the stations taper off. Until recently, $5 billion in federal funding was set to change that, with a nationwide goal to build a network of public EV chargers along every 50 miles of designated roadway from Maine to California.

Known by its acronym ‘NEVI’ in the EV and policy worlds, the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program was brought to a halt by the Trump administration in February.

But the memo released on Feb. 5 by the Federal Highway Administration, which manages the program, drew confusion among states, leading some to halt construction while others pressed forward. Many, including Maine, have multiple NEVI-funded sites underway.

Building these sites is expensive. In Maine, $19.3 million in NEVI funding has been awarded to the state to install level three fast chargers, which can add 100 to 250 miles of charge in 30-45 minutes. The chargers, which have several ports to plug into, start in the tens of thousands of dollars. So far, Maine has inked plans to install a total of 62 ports across the state using $11 million of that NEVI money.

According to data compiled by Efficiency Maine Trust, the quasi-state agency for energy programs that handles reimbursement for the program, 15 sites have approval to use NEVI dollars, though two have since been cancelled. Two others were completed last year in Augusta and Rockland, making them among the country’s first NEVI-funded stations to open.

As for the rest of the sites, the Feb. 5 memo was vague about how NEVI’s suspension will impact their construction. While it states that the FHWA is “immediately suspending the approval of all State Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment plans for all fiscal years,” and directs states not to undertake “new obligations,” the memo also says the government will reimburse existing obligations “in order to not disrupt current financial commitments.” The government doesn’t pay for projects until after the fact, by reimbursement.

In the two months since the memo came out, EV expert Loren McDonald said some states are taking the ambiguity as a green light to interpret the guidance in accordance with their own goals. McDonald is chief analyst at Paren, an EV data platform tracking how states use federal funding.

“There was somewhat of a red state, blue state divide, not a hundred percent, but red states basically interpreted the FHWA memo as saying, stop everything you’re doing,” said McDonald. “Most of the blue states said, continue ahead with construction, breaking ground, anything you’ve already been legally contracted and awarded by us — we’re not stopping.”

While the legalese behind government funding obligations gets complicated quickly, the general consensus is that projects with contracts already in place can’t just be rescinded by the FHWA.

Barry Woods oversees e-mobility at ReVision Energy, which has NEVI sites underway in Ellsworth, Portland, Bangor, and Rumford. Woods said they sent paperwork for two of the sites to the state for further approvals just last week.

“I’m pretty confident that Efficiency Maine, as far as the NEVI funding goes, feels that any awards made to date will be honored,” said Woods.

Damian Veilleux, a spokesman for the Maine Department of Transportation, confirmed that they plan to honor NEVI funds that were obligated for building level three fast chargers across the state.

Beyond NEVI, Maine was also awarded $15 million from the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure Discretionary Grant Program, which will fund public EV infrastructure in urban and rural areas and along major roadways. The CFI money can be used to build level two chargers, which fill a car in several hours. McDonald calls them ‘destination chargers’ and said they can be a boon for communities.

“Having level two charging in towns and at bed and breakfasts and at ski resorts and things like that are absolutely critical, and potentially as or more important than fast chargers along the highway,” McDonald said.

While the federal government has yet to announce any changes to the discretionary grant program, there are concerns that it will face a similar fate to NEVI. Woods said Maine has already gotten most of the CFI money out the door by obligating it to projects across the state, including two with ReVision Energy in Old Orchard Beach and Gray.

Looming auto tariffs pose another potential threat to EV infrastructure, but both McDonald and Woods said private investment shows the EV market is maturing. In the past few years, Walmart and Mercedes-Benz have joined the ranks of Tesla and other EV charging companies to build infrastructure. Those investments, though, center around urban areas where utilization rates for fast chargers are higher, driving down utility costs.

Maine’s utilization of chargers hovers at 5 percent, according to Paren’s data. Comparatively, some fast chargers in the San Francisco and Los Angeles markets see 80 percent utilization. Building in Maine just isn’t as profitable for private investors right now, McDonald said.

That’s where the federal incentives come in. Along the upper stretches of I-95 and in the places the highways don’t reach, there’s still a need for chargers. This is particularly true during the summer months when visitors are passing through.

“We have tourism that we’ve got to be responsive to as an economic sector,” Woods said.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit civic news organization. To get regular coverage from The Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.