Eric Green: Classic New England Road Run, Kris, and the Summer of 1975

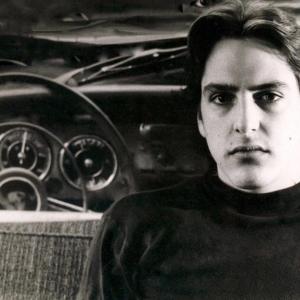

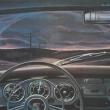

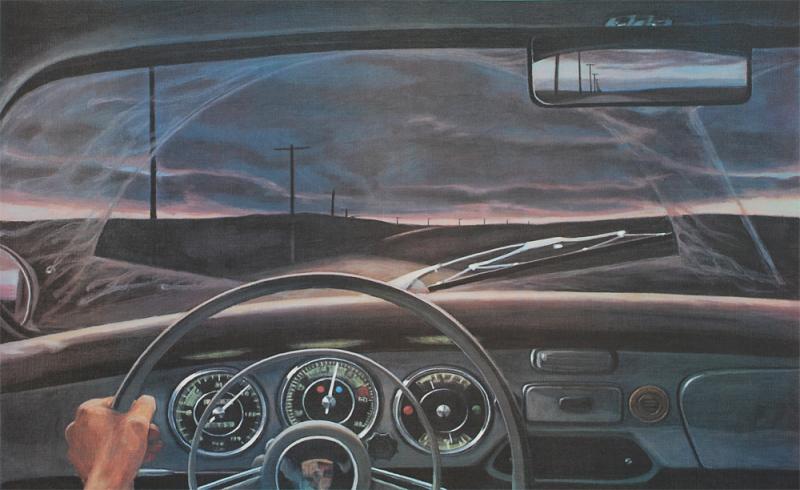

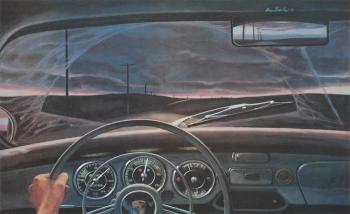

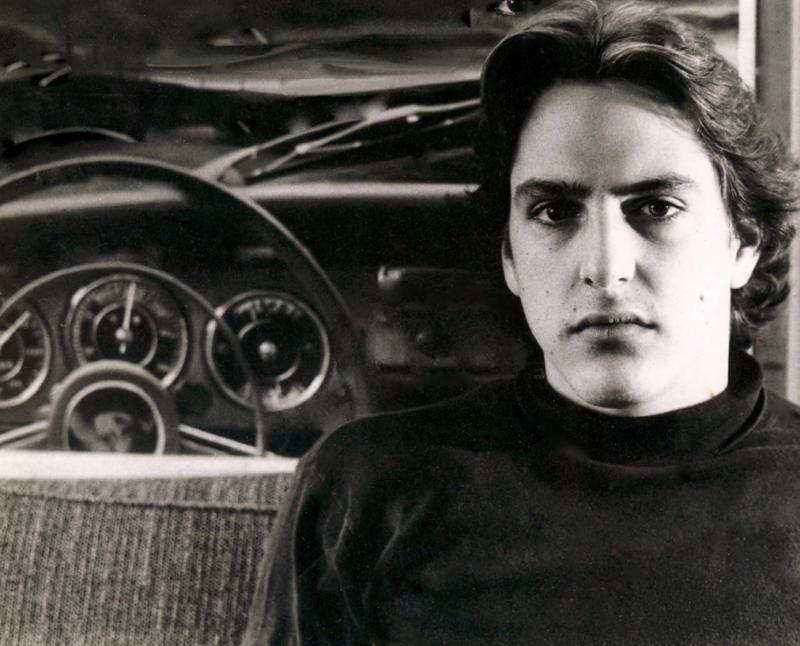

Eric Green painting of his 356 Porsche dash, 1976

Eric Green painting of his 356 Porsche dash, 1976

1956 Porsche 356 on the Maine Coast in 1975

1956 Porsche 356 on the Maine Coast in 1975

Kris Marsala and Eric green in Belfast Maine 2018

Kris Marsala and Eric green in Belfast Maine 2018

Eric Green painting of Archies poolroom once in Gorham New Hampshire, 1976

Eric Green painting of Archies poolroom once in Gorham New Hampshire, 1976

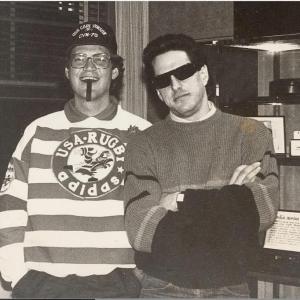

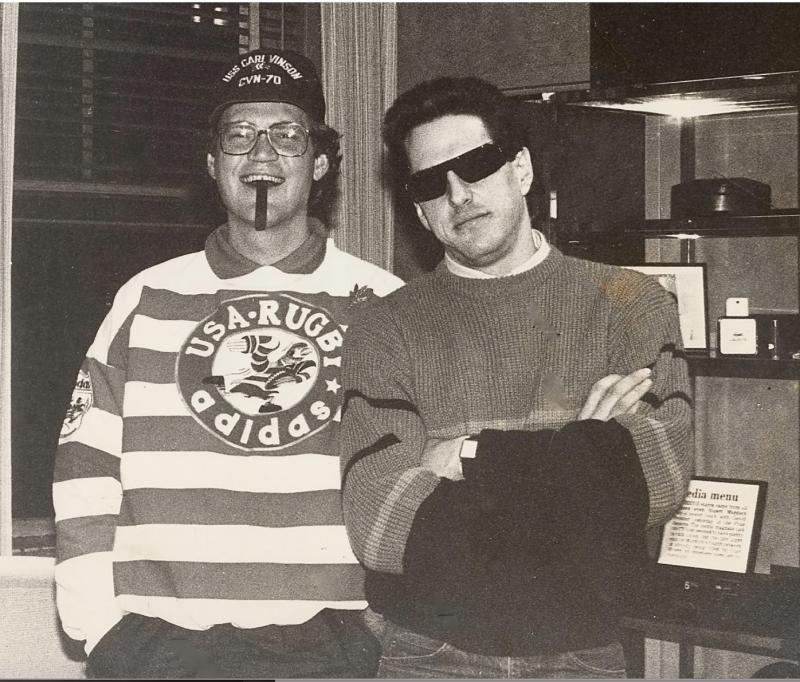

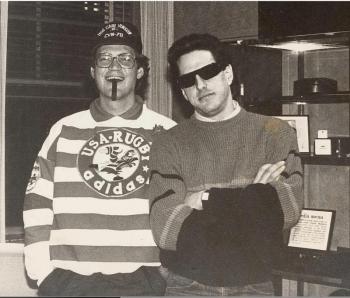

Letterman and Kris Marsala

Letterman and Kris Marsala

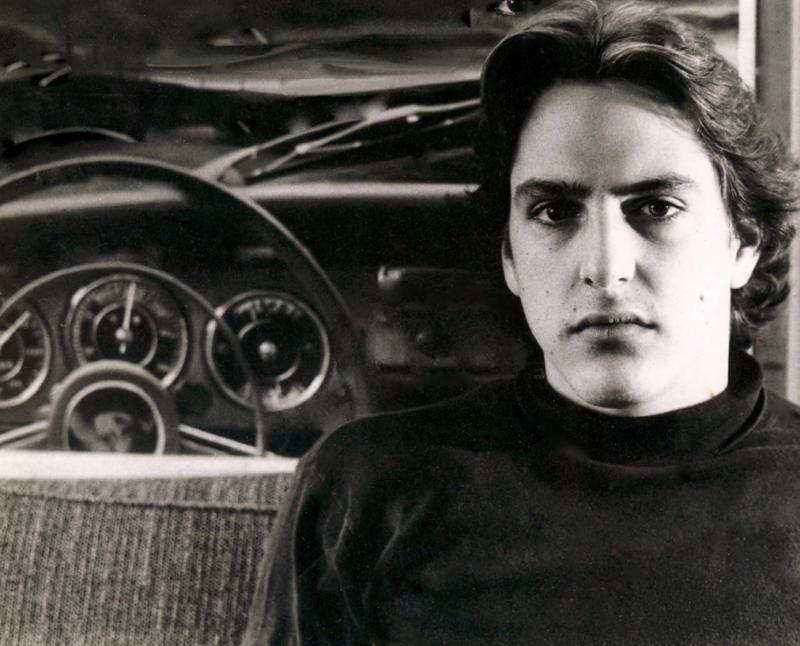

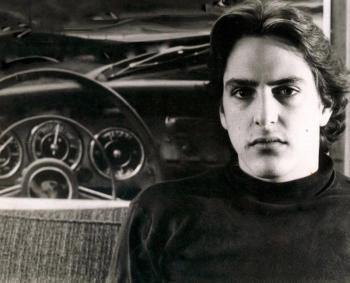

Kris Marsala and Open Road painting. Photo: Eric Green

Kris Marsala and Open Road painting. Photo: Eric Green

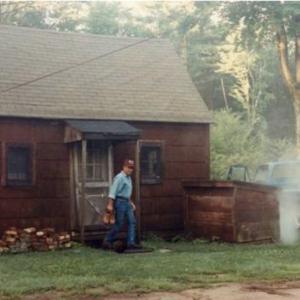

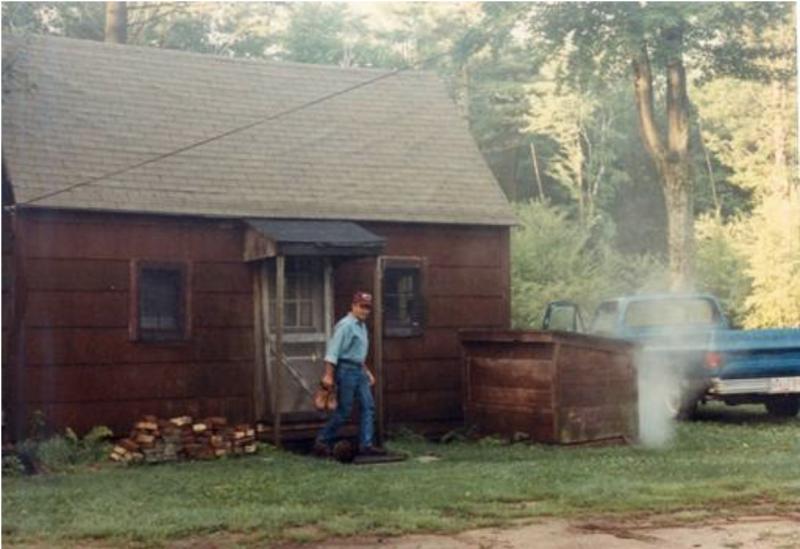

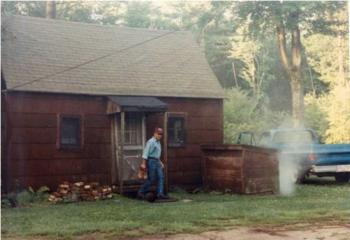

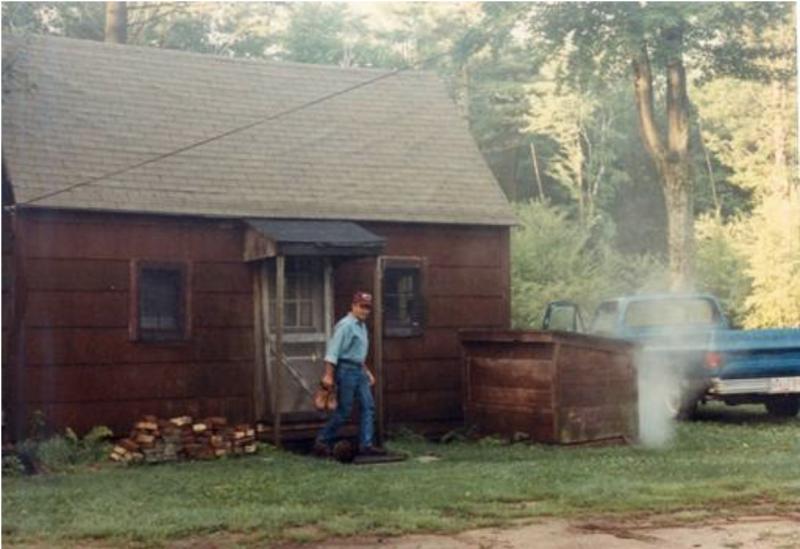

Hal Stowell exiting his cabin in Wendell. Photo: Eric Green

Hal Stowell exiting his cabin in Wendell. Photo: Eric Green

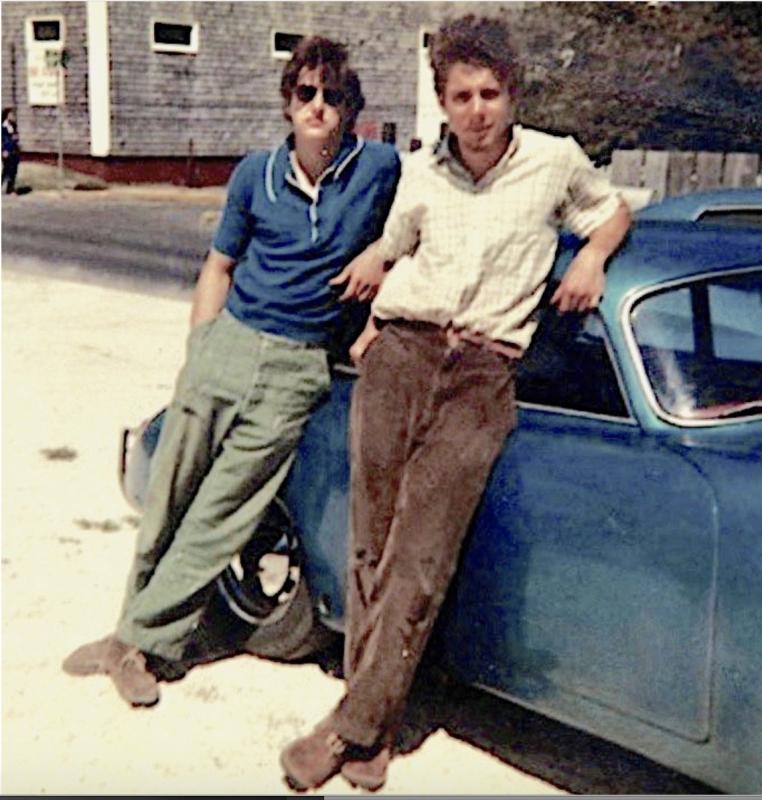

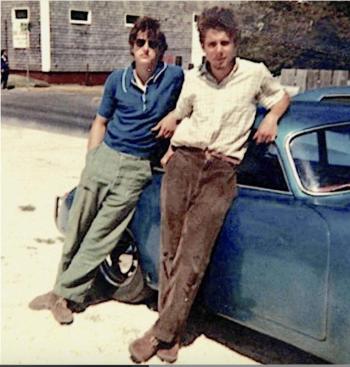

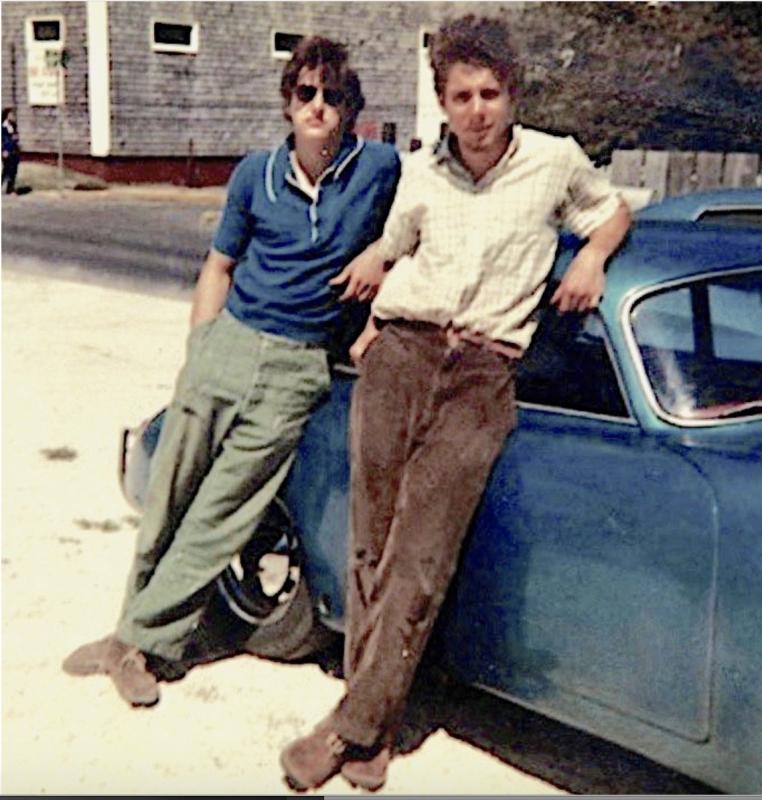

Kris Marsala and Eric Green in Provincetown, 1975. Photo: Penelope

Kris Marsala and Eric Green in Provincetown, 1975. Photo: Penelope

Bruce house in Woods Hole. )Photo courtesy Rich Bruce)

Bruce house in Woods Hole. )Photo courtesy Rich Bruce)

Eric Green painting of his 356 Porsche dash, 1976

Eric Green painting of his 356 Porsche dash, 1976

1956 Porsche 356 on the Maine Coast in 1975

1956 Porsche 356 on the Maine Coast in 1975

Kris Marsala and Eric green in Belfast Maine 2018

Kris Marsala and Eric green in Belfast Maine 2018

Eric Green painting of Archies poolroom once in Gorham New Hampshire, 1976

Eric Green painting of Archies poolroom once in Gorham New Hampshire, 1976

Letterman and Kris Marsala

Letterman and Kris Marsala

Kris Marsala and Open Road painting. Photo: Eric Green

Kris Marsala and Open Road painting. Photo: Eric Green

Hal Stowell exiting his cabin in Wendell. Photo: Eric Green

Hal Stowell exiting his cabin in Wendell. Photo: Eric Green

Kris Marsala and Eric Green in Provincetown, 1975. Photo: Penelope

Kris Marsala and Eric Green in Provincetown, 1975. Photo: Penelope

Bruce house in Woods Hole. )Photo courtesy Rich Bruce)

Bruce house in Woods Hole. )Photo courtesy Rich Bruce)

Classic road trips do not begin as classics. It’s not as if two guys look at each other one morning and say, “You in the mood for a classic road run?” And the other guy nods, “Sure, why not?” Nothing like that at all. And many times it’s only after the run is completed and ferments in the memory for a number of years, that it becomes classic.

But my run with Kris Marsala around New England that summer of 1975 driving my blue 1956 Porsche 356A Super coupe is a true stand out. A true classic.

It began innocently enough. Kris was 21 years old and at the height of his handsomeness and cool. I was maybe at the height of my fearlessness, having ridden freights the year before, hitchhiked over 15k miles; I was a weathered tough road guy of 18 years old. Although I wasn’t lifting weights yet and hadn’t learned to box yet, my pool hustling skills were formidable, my Willie Hoppe pool cue always at hand, and my heart had not been dimmed by the world, or completely broken as it would be soon enough. I had a true positive rage to live—likely fueled by my many years of childhood illnesses and 22 hospital visits—and Kris was more than willing to accompany me on the road.

As we set out (unusually vague in my memory) we headed east across upper state New York on Route 11. We must’ve stopped at McCarthy’s diner because at that time it would’ve been impossible for me to drive past any classic diner without at the least a quick pull in for a coffee. I drank an inordinate amount of coffee during this era, which ended in around 1980 when I discovered coffee wasn’t a health food as I’d thought. Bleeding ulcers shortly after ended my coffee craze forever. But at that time I ground my own beans by hand, and always carried my espresso vacuum pot (hilariously even to Europe—I brought sand to the beach). Even on the freights I had a single cup drip coffee maker and always drank from my prized G.I. mug. The stain inside was a thing of great value to me although Kris’s mother, Edie, once scrubbed it clean by mistake—this was one of the only things Kris remembered from that summer.

Among other story gems, McCarthy’s is the diner where Hal Stowell, my poet friend and general mentor during my teens, knocked a dime-sized hole into his stemmed cocktail glass while over-energetically stirring his noon Bloody Mary after soaking up endless beers from Montpelier, Vermont to McCarthy’s. The thick red drink silently exited his glass onto the Formica tabletop as he gazed drunkenly into whatever space drunks gaze. His next sip was an empty icy surprise. I, of course, fell off my chair laughing, annoying everyone. Why do so few people embrace true joy in others? I guess their lives are just too dull and angry for them to embrace anything except more of the same.

After a coffee and fresh-made cinnamon bun, Kris and I continued along the remote bleakness of Route 11 across the top of the state, past the green vertical neon of the Casablanca sign, through the lost towns of Canton and Potsdam, and eventually over Rouses Point into Vermont.

Strange to think my parents had not yet quite moved to Morrisville, or later to Waterbury Center, where my mother would live until 2005 when I moved her to Belfast, taking care of her for the last 4 years of her life. I’m sure we stopped at the hobby shop in Swanton and the Blue Lion in St. Albans because I always made the same stops that my father had made during my childhood. What wonderful memories that hobby shop held because even then I was obsessed by model trains. It was the first excitement of summer vacation on our way from Watertown to Beloin’s Cabins in Camden, Maine.

Hal Stowell’s cabin during that time was my spiritual home, and Hal was always welcoming, which, as I look back from this mature viewpoint, is kind of amazing. I simply don’t open my door if visitors don’t call first, and if they catch me in the yard, I’m rude and annoyed. I can’t abide drop-by visitors, and it has cost me some friendships, none I’ve minded giving up.

But Hal always had a warm greeting and always met the poetry of the moment, which must have been exhausting because of my intensity. Everything mattered so much to me then. And I’m probably not much better now, but maybe wiser as to overwhelming people, or maybe not (I do try). I can hear a few people snickering. My response: “Try my brain for a few weeks and then report back.”

Of course I always called first and brought beer. And I always searched the homespun package stores around Wendell, Massachusetts, for something interesting: Rolling Rock when it first showed up in New England with its stubby green bottle and tiny label. Later it would go to the impressive silk-screened long neck, Black Horse Ale, Pickwick Ale, Ballantine’s or the rare Ballantine’s I.P.A that was actually and truly aged in wood for 9 months. Narragansett and Haffenreffer and Black Label pounders.

After the obligatory classic visit with Hal—Kris and I taking Hal out to the Spring Hills Diner for supper in the 356 and staying overnight at the cabin—we headed for Providence to search out the friends who had lived over Duke’s Poolroom on the third floor. It was bizarrely hot, but the Porsche seemed to run fine in almost any temperature condition—from -15 to over 100 degrees f. As I’ve said, 356 Porsches were phenomenal cars as they left the factory; it was the carelessness of bad mechanics and owners who ruined them.

But when we reached Providence, stopping at a bizarre massage parlor in a cement strip of 1970s buildings (nothing quite as ugly ever again) on the way down, everyone I knew had long since moved on. It felt strange, maybe for the first time in my life, to sense that things did not last. When I returned to Providence during the 1990s, the entire area I knew had been razed.

We left the heat of the city and pointed the Porsche to Cape Cod, for the cool air as much as anything else. Heat or not, Kris was still yelling his classic Mille Miglia cry of joy. Kris loved to hang out of the Porsche window, half his body out of the car, showing off his well-muscled naked torso, screaming at the cute girls or just trees, “It’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia,” over and over. It should be noted that Kris at this time smoked pot continually—from the moment he awoke to when he settled for the night. He even swallowed the roach ends, telling me that the more THC in his system the better. I, on the other hand, never touched the stuff, and felt that it did not improve Kris’s insensitivity or obnoxious arrogance.

Rich Bruce’s mother had an amazing house in Woods Hole that was just off the main road on the right before the lift bridge approaching the sleepy downtown that it was in 1975 because Martha’s Vineyard had not been “discovered” yet. We called Rich, and spent a few days with him and his wonderful mom, Edith, a true free-thinker from the old school. She was the stuff!

That night we swam in the calm black ocean, which after the long drive and the blazing city was everything you wanted it to be. I should point out that Rich was a fair match for Gregory Peck during his 20s, so when we drank draft beer at the crowded Captain Kid that evening, I didn’t even consider talking to girls, assuming no female would choose a misshapen aardvark over two tall well-built movie star types. Women were always on my mind, and I must say, Kris for all his faults, had been obsessed with females his entire life. He truly loved women. Not that many men do, regardless of anything.

Kris and I could not have been more different when we first met again after high school. Of course I never finished high school, leaving after my junior year to attend RISD at 16 years old. And although I’d known Kris since I was two, being a couple years older than me, and being the most popular boy in school, he ignored me when our parents got together.

I was an original outsider type, and although the other high school students knew who I was (because the much-loved anthropology teacher gave a lecture about me stating I was the only unconditioned student he had ever encountered in 20 years of teaching), I was always by myself, eating my mother’s strange sandwiches outside behind the school—winter or summer—never in the cafeteria, or hanging out at an abandoned farm or in the extensive freight yards around Neenah, Wisconsin, where the family had moved from New England in 1971. And I was working on my painting up to 14 hours a day. Painting bugged me. It challenged me. It annoyed me. I never wanted to be a painter. I had wanted to be a poet. But when I began selling work as a teenager . . . and Kris’s dad Chuck was one of the first people to buy my work. His wife Edie called him from the Midwest where she had fallen for two of my paintings and couldn’t decide which one to purchase. Chuck’s response? “Buy ’em both.” That was another $825 in 1974, and I’d learned by 1975 not to loan my dad any more money.

Kris’s father had done very well in the car business, had a huge AMC Rambler dealership with a body shop and multiple bay repair shop called State Street Body Works. The family was wealthy by my standards, with an in-ground pool, a white living room, with white shag carpet, white brick fireplace and a grand piano (black), full five-stool bar with neon lights and pool table in the basement where I always slept, a cottage on the river, and Kris always had a free Rambler of his choosing and a gas card! This was amazing to me, who was always loaning his broke father money and who grew up in four-room ranch houses. The Marsala mansion even had a drawbridge heading to the front doors, which I can’t remember ever being used. They even had a TV room with a massive color set and wraparound sofa, where as my family never owned even a B&W.

Kris was a hugely popular guy in Watertown along with his steady, the gorgeous Lisa Beaverson, who would soon enough dump him and run off with a much older balding bee keeper. I’m not sure Kris ever got over this first great disappointment in his life. He used to say, “So, you know, I asked her how it was with the bee asshole, and she looked me right in the eye and grinned, ‘It hurt! Is that what you want to hear? And I loved it!’ Jee-sus! Talk about cruel,” Kris would moan.

But all said and done, Kris had an addictive cool, a tough powerful style that matched the body, was an amazingly fast runner with a hilarious dry, self-depreciating sense of humor. Of course, he also wanted to be an artist and a poet and a singer. He would eventually have a successful cable talk show called “The Krazy Kris Show” that even Letterman liked.

Kris also had perfect skin, which I much envied, not to mention the massive arms and chest like Marlon Brando that Kris always showed if the temperature was above freezing. So there I was, extremely skinny, uneven complexion, yet I must have had something Kris wanted or liked because he latched onto me. I guess I’ll never know what it was.

I took driving very seriously because my father, an ex-racing driver, had begun to train me at my begging in racing moves on gravel at 14 years old. I practiced incessantly, as I did with anything I wanted to master, and by 16 I could double clutch, had a perfect toe-heel change, could slide cars in the wet as well as the dry, could shift without touching the clutch if needed, could spin a car using the handbrake at speed, and so forth.

I always wore Italian leather racing gloves, and each section of a road run was like a race for me. In the 356 Porsche, I was only passed three times on secondary roads over the years I had it, once by a Lotus, once by a 911 Porsche, and annoyingly once by a Chevrolet Nova hotrod that pulled beside me at over 100 mph and then simply disappeared—laughing. I was the only kid who passed the driving test on my first try. If you made even the slightest error, you flunked. I had a perfect test. This really annoyed Eric Murphy and Peter Verbrick, my two high school friends.

Leaving Rich Bruce, such a gentle quiet soul back then, we headed out through Edward Hopper territory to the tip of the Cape. When we decided at mid-afternoon for a swim, I was arrested by a female cop for nudity. I always swam naked, so at first I figured it was a joke. It wasn’t, and she almost cuffed me! Being naked, I wasn’t carrying any identification, so we walked back to the 356 together, I feeling odd naked next to a female cop; I was shy then about my physicality. But on seeing the car, she offered to forgo my ticket if I gave her a ride. I agreed. “Now, how do you want me to drive? Are you going to give me a ticket for speeding or reckless driving?” She told me to go for it, and believe me, I gave her the ride of her life. When we returned to the impatient Kris, she was quite flushed. “Wow, that was simply amazing.” This might be a first and a last.

Gayness wasn’t the same in 1975 as it is now, in the sense that it wasn’t overt or even particularly interesting. None of the friends I knew cared if you were gay or not—it just wasn’t an issue. Fine either way was my feeling, and I was actually attacked once on a train in Europe when I was 13. Being a soccer player I destroyed the rapist’s shins. Then, at 14, I was accosted in the middle of the night waiting for a bus in Portland, Maine. Later, after riding freights and hurting my head jumping off a train stupidly, I was messed with in the restroom of the Spokane, Washington, bus station.

Provincetown in 1975 had a lot of homosexuals. Kris and I, always intently looking for girls, couldn’t figure out what seemed different. Kris immediately picked up a luscious English girl, Penelope, in a lunchroom where we had gone for a sandwich and a coffee. She explained the situation to us, and suddenly the bulb lit.

That evening, the three of us went to Penelope’s favorite tavern, and I spent the evening hustling pool. I made an inordinate amount of money, well over a hundred dollars. It was almost as if all these gay guys just wanted to give me money. They were amazingly friendly and funny, and I had a tremendously good time. After about three hours, I went to check on the love birds. Kris was apparently in the washroom, I’m sure to smoke more pot. I sat down beside Penelope and said the obvious, “You have the most beautiful eyes I’ve ever seen.” I said it because it was true. The palest blue, huge, dark prominent lashes against the whitest skin.

Kris ended up sleeping in a rubber boat on Penelope’s porch, and when it began to rain during the night, the boat quietly filled with water. Kris was the proverbial wet hen in the morning.

I was crazy about Penelope. A few months later when I returned from Europe, I visited her at her college in Maryland, but she had another boyfriend by then. She was too gorgeous to leave alone for months, and I was as far from settling down as a boy could be. We sat in the manicured lawn outside her dorm room, my Porsche looking stunning in the late afternoon sunlight. I took three early autumn leaves and carefully removed the centers as we talked. When I painted Penelope that winter from a nude drawing I’d done that Provincetown morning, I painted in the three leaves.

The Maine Coast has always been my favorite place on Earth, and to live here is a daily joy. I simply like everything about it, and the true Mainers exemplify what I admire in people as well, although I’ve always preferred animals and nature to most people. After all, I’m misanthropic, melancholic, quite agoraphobic now, as well as germaphobic and reclusive—a hermit who loves only one woman and cats—Maine Coons. Perfect combination of attributes for Midcoast Maine.

Kris and I stopped in Boston to visit Peter C. and after I took him through the streets of the city at intolerable speed, I noticed the tires looked peculiar. It was the dirty canvas backing protruding through the rubber in far too many spots; overly energetic hard 4-wheel drifts on dry pavement will do that. New Uniroyals fitted (funny I remember the tire manufacturer), we pointed north after a good night’s sleep at Peter’s family’s glorious apartment in Cambridge filled with rare harpsichords and spinets that his father had collected or made. Kris’s night was far drier, mine far less wet, but all road heroes need sleep on occasion.

It began to feel like Maine when we stopped at L.L. Beans. If you’ve never been there in the 1970s or earlier, you’ve never been there. It was simply the best then, and no wonder it became so famous.

But also the narrow passage up to the old Bath bridge, such a rumble over the metal grid, which I attacked just a tick under 80 mph, and the nostalgic pass through Wiscasset ( these wonderful Native American names!), the sinking schooners still signaling the glorious windjammer past with a rotten wooden mast or two before they eventually vanished. How I loved the sight of those schooners as a boy. Of course nothing says Maine to me more than a stop at Moody’s Diner. The tiny washrooms could make a grown man cry, and that worn yellow counter linoleum where Kris and I sat, rubbed our summer-tanned forearms across, adding patina. What wonderful sensibilities to keep something like that and not to change it, but that’s the gift of a family-owned business that stretches for generations. The hot turkey sandwich on a grilled homemade biscuit!

For me, the most memorable part of the whole run was now. We stopped at the Smiling Cow in Camden, the place where I’d purchased my first art supplies in the 1960s—simple felt-tip pens and sketchbook pads of drawing paper—and after walking out onto the back porch over the tidal river, gazing at Camden harbor, we realized (were told) that the last Islesboro ferry was leaving in under five minutes.

Okay, I’m guessing here, but I would wager few cars have ever passed that distance quicker than that blue coupe on that June afternoon. Gloves on, I was flat out—and Eric Green in 1975 in his Porsche 356A Super was pretty quick. I 4-wheel drifted (new Uniroyals!) off Route 1 as the ferry was just inching away from the slip. The lads on the boat—God bless them!—signaled, and I jumped the slight difference to cooly place the 356 on the boat deck. Kris, of course, was calling out his mantra with wicked abandon. It was one of those crystalline summer moments that few get more than once. There, Kris! We will always have that.

Kris and I visited Uncle Don (in name only) who had a house on Islesboro and whom I’d known since 1970 when I first visited the island with Chris Todd. Many of my firsts happened on Islesboro, like skinny dipping at night with girls at fourteen, or smoking my first corncob pipe, bought off the rack at the country store there, with Borkum Riff because I wanted to connect myself with the square-riggers printed on the pouch. Uncle Don thought I was brilliant for figuring out how to drill a hole in a hand-carved pipe stem. I burned it through with a red-hot piano wire heated on the gas stove. I learned from Mitch the other day that this was how Mainers made syrup spiles out of sumac. As an aside, my father could’ve bought 8 prime waterfront acres in 1968 for 2k. “Not a good buy,” he claimed to convince my mother who was all for it. “No one will ever want to deal with that ferry.” Thanks, Dad.

Donna was Uncle Don’s daughter and Donna was getting married the next day at 18 years old, my age. It seemed way too young to get married although I would marry just a year later. To celebrate with a kind of co-ed bachelor party, the three of us set off around the island in the Porsche with lots of beer. I think it was Tuborg or Labatts. We ended up next to the ocean in a moonlit bit of beach. The three of us enjoyed this greatly until it was discovered that Donna’s engagement ring had vanished, which she desperately needed in mere hours. We sifted sand until dawn, and strangely I can’t remember if we ever found that ring or not. I do remember the sad weary blueness of all that sand in the hung-over dawn—we all felt terrible. Donna got married that day, and Kris and I slunk off on the early ferry back to the mainland.

The ferry docked at Lincolnville Beach where I had camped so many times during my past hitchhiking days. We stopped in Belfast, but once again could not find Sam Appleton although his restaurant was finished and operating. Leaving Belfast during that era, I always took the Moosehead Trail and then Route 137 through the rolling dairy farms. Same route I hitchhiked in 1973. I always utilized roads with cool names like the Mohawk Trail or the Pilgrim Highway, which filled me with romantic dreams.

Most early Maine roads were built across ridges and then they dip down to water—streams, rivers, lakes, where the towns congregate around since water was so vital. Dirt path from settlement to settlement, which were eventually widened and then paved, missing the correct base of gravel and drainage to prevent frost heaves. We drove past the paper mills of Skowhegan and Rumford, the stench in Mexico all but unbearable, an actual slap to the face and then an immediate sleeve to nostrils. It reminded me of Gorham when the Brown Company reek blew down the Androscoggin River. Of course I adored all this kind of thing back then, and still know a lot about paper mills and paper making, all my father’s inventions being within that industry. My father actually invented the foil and the Verti-former.

Entering the White Mountains and arriving in your hometown, driving an early 356 Porsche, your own Porsche at the age of 18, after driving with your father so many times in his Porsches is a feeling beyond words. Past the Shelburne Birches, past Reflection Pond, past the Town & Country Motor Lodge, over the railroad tracks and the Peabody river (pronounced Pibbidy river) and up the steep drive to Prospect Terrace and the last house of three, my Godmother’s grand Queen Anne Victorian. Oh man, oh man!

Of course we played straight pool at Archies and drank a couple birch beers, a pop which I’ve never seen outside of northern New Hampshire. And for the one and only time, Kris beat me at straight pool. He couldn’t miss a shot—perhaps the exact blend of pot and lack of sleep. I kept going outside to admire the sight of my beautiful blue coupe parked next to my favorite ever poolroom.

We went to a bar then, always looking for cute girls, probably up in Berlin, maybe the Club Joliette de Raccateurs, and at about midnight, I decided we would head for Lake Placid where Kris had a girlfriend he wanted to visit. I remember this old guy who owned the gas station where Route 16 joins Route 2, which then sets out alone for Vermont across the north slopes of the White Mountains, this old guy, really drunk, turned on one of his pumps so we could gas up, a lovely gesture, Kris and I then push-starting the 356 up the slight incline that became the enormous rise of Gorham Hill.

The headlights began to dim to the point where I simply had to shut them off just to keep enough juice in the system to fire the plugs through the coil and distributor. I stopped a few times to whack the voltage regulator, but the old generator was too worn to do much good. (Soon Inky Wardwell and I would replace the brushes in Sacks Harbor.)

Kris kept falling asleep, and his head would snap backwards cruelly into nothingness because the Porsche seats did not include headrests. He’d wake from the pain, mumble illegibly and then repeat. This must have happened fifty times. It was a glorious run while the moon was out, but bizarrely dangerous when the clouds closed over our only light, and I put the car into a few panic slides to keep her from the void of true darkness and disaster. Kris bizarrely slept through it all.

I had not at this point memorized Route 2 from so many crossings as I have now. In the last ten years much of the road has been straightened, and I no longer take the original pure Route 2 run through Lancaster, New Hampshire to cross the Connecticut River at Lunenberg, Vermont and enter what Stan Walker always called, “The Waste Lands.”

The dawn lightened the world when we reached Rouses Point and Lake Champlain. I stopped the Porsche and simply got out and lay down exactly on the center white line, the lake perfectly reflecting the rose colored sky to become one like a vision of God. I was so elated I wasn’t even really tired although I was entering my third day without any sleep. I felt the cold damp Macadam on my back, I heard the 1600 tick as she cooled, I looked up at the sky and knew I had done it, achieved it, truly felt it—the road, the blessed road. 15 minutes of silence and bliss.

Then I gave the car a light push, jumped back in, slipped the clutch in second gear and off we continued.The toll bridge into New York State took our last coins leaving us 17 cents. I begged the sleepy guy in the booth—I’d woken him and could’ve just driven right by—but he insisted we pay. Now we didn’t have quite enough money for coffee, and we really needed coffee more than the state needed our 50 cents. I couldn’t get on a pool table till afternoon, and I hated to play broke. It was poor ethics although sometimes it was unavoidable. That said, I very rarely lost when hustling. And then we arrived at the girlfriend’s apartment and Kris disappeared with her, as I fell asleep on a dirty sofa. It was about 8 a.m. on a Friday morning in late June 1975. That road run had ended. They all do . . .

Event Date

Address

United States