Big Pharma, James Taylor and the NRA

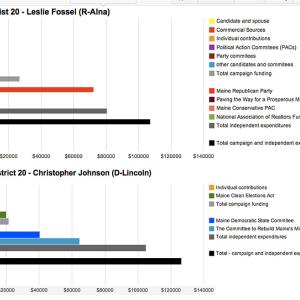

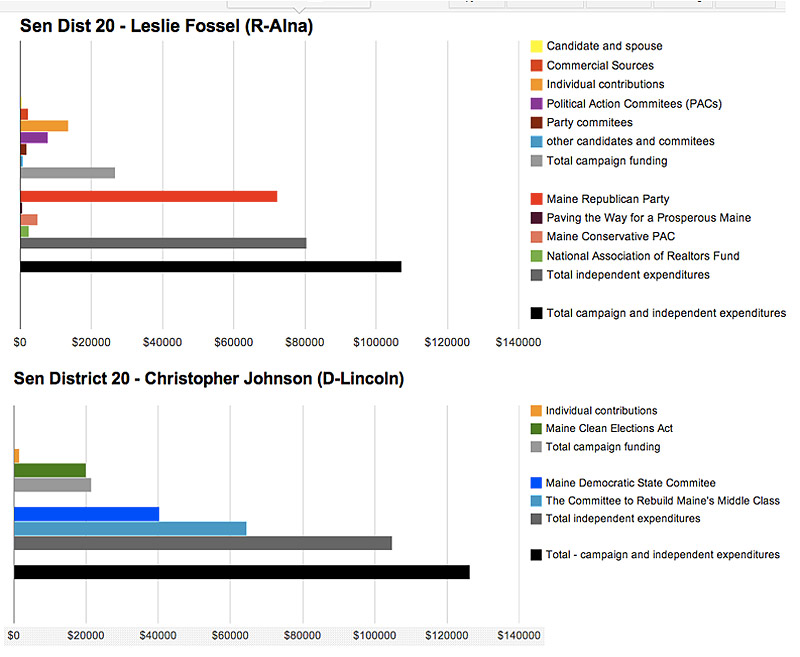

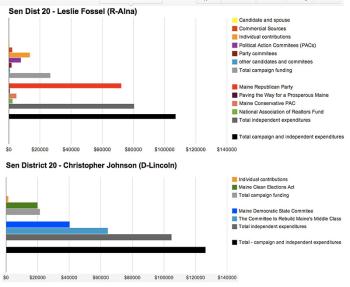

In Maine's Senate District 20 race, incumbent Leslie Fossel (R-Alna) raised more private campaign money, but challenger Christopher Johnson (D-Lincoln) had strong backing from the education and labor union PAC, The Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

In Maine's Senate District 20 race, incumbent Leslie Fossel (R-Alna) raised more private campaign money, but challenger Christopher Johnson (D-Lincoln) had strong backing from the education and labor union PAC, The Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

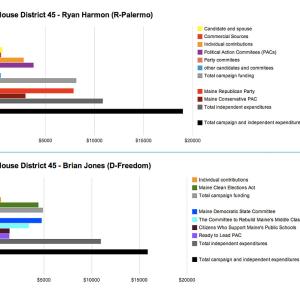

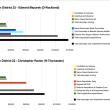

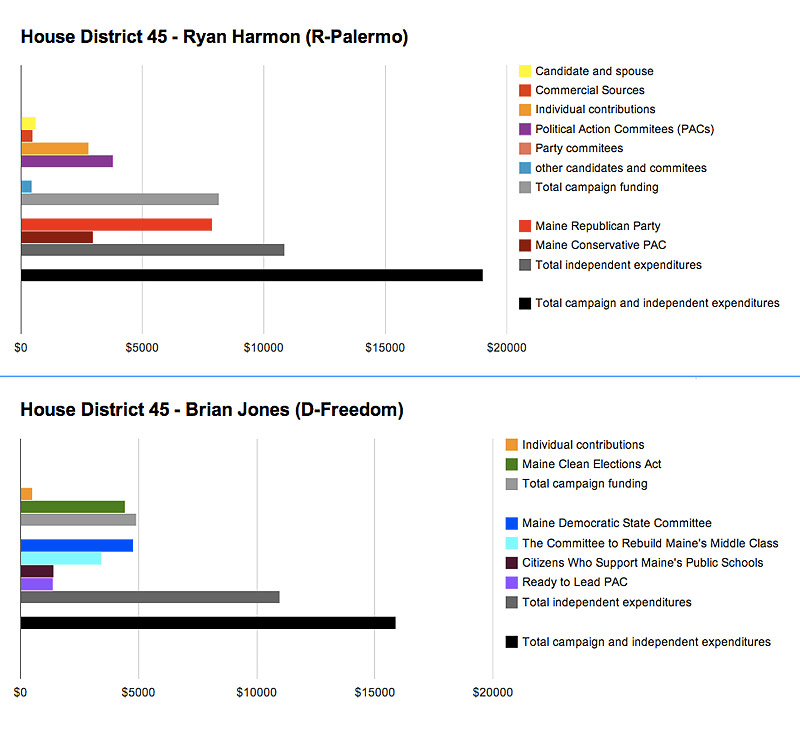

Spending on each of the candidates in the Maine House District 45 race came from very different sources. Rep. Ryan Harmon's was notable for being the only privately-funded campaign in Waldo County. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Spending on each of the candidates in the Maine House District 45 race came from very different sources. Rep. Ryan Harmon's was notable for being the only privately-funded campaign in Waldo County. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

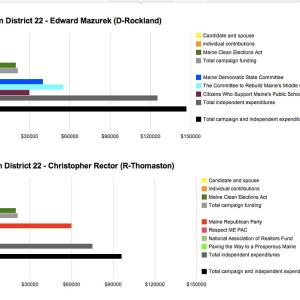

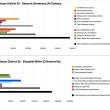

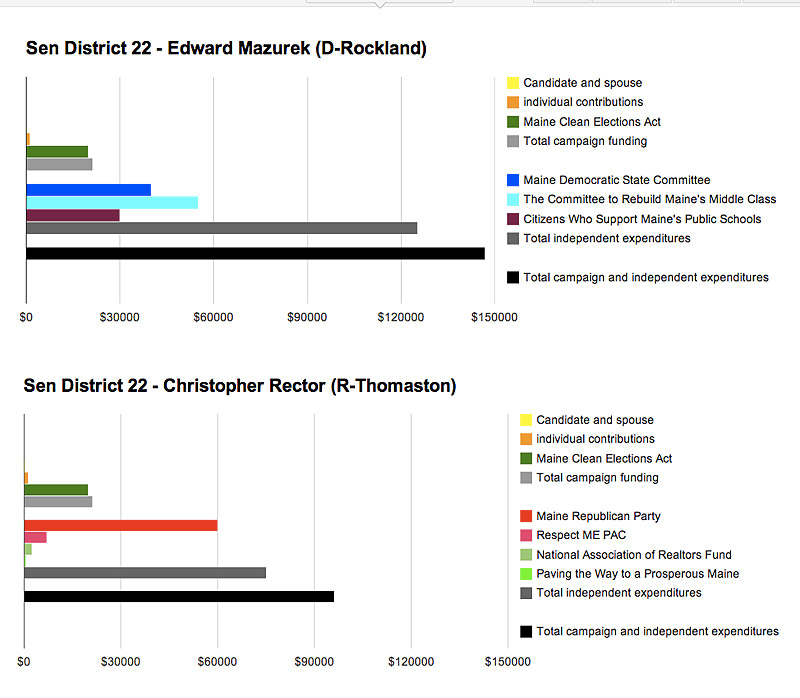

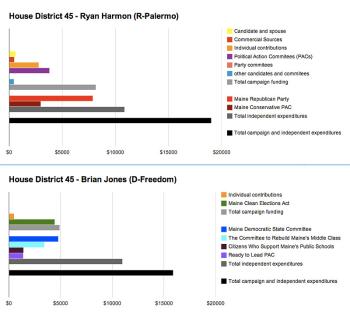

The sixth most expensive race in the state and most expensive in the Midcoast was the contest for Maine Senate District 22, in which both candidates attracted large amounts of spending by the political parties and outside PACs. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

The sixth most expensive race in the state and most expensive in the Midcoast was the contest for Maine Senate District 22, in which both candidates attracted large amounts of spending by the political parties and outside PACs. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

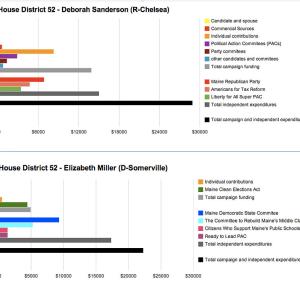

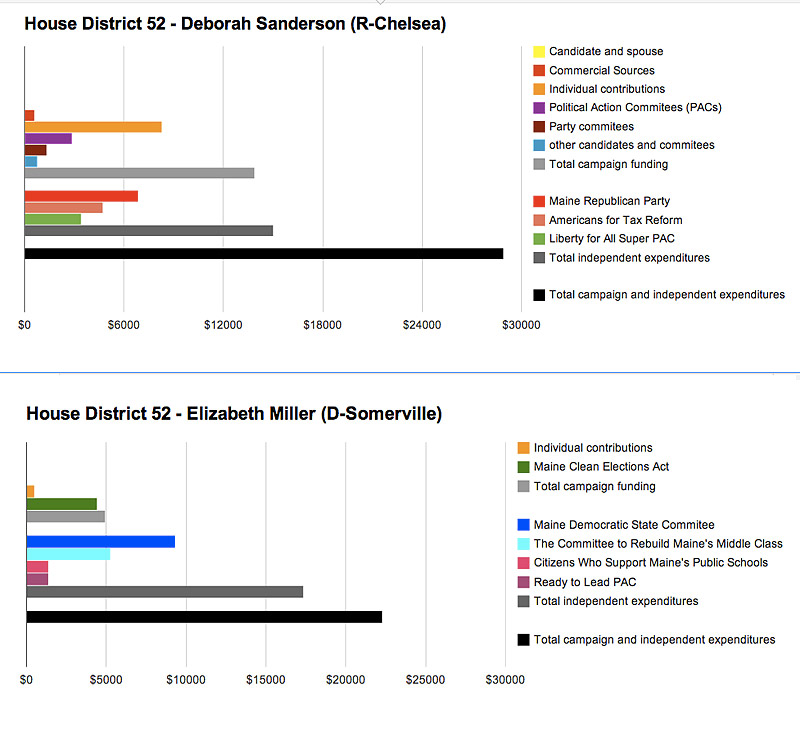

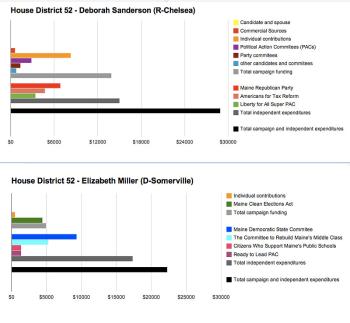

Campaign spending in the Maine House District 52 race between incumbent Rep. Deborah Sanderson (R-Chelsea) and Elizabeth Miller (D-Somerville). (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Campaign spending in the Maine House District 52 race between incumbent Rep. Deborah Sanderson (R-Chelsea) and Elizabeth Miller (D-Somerville). (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

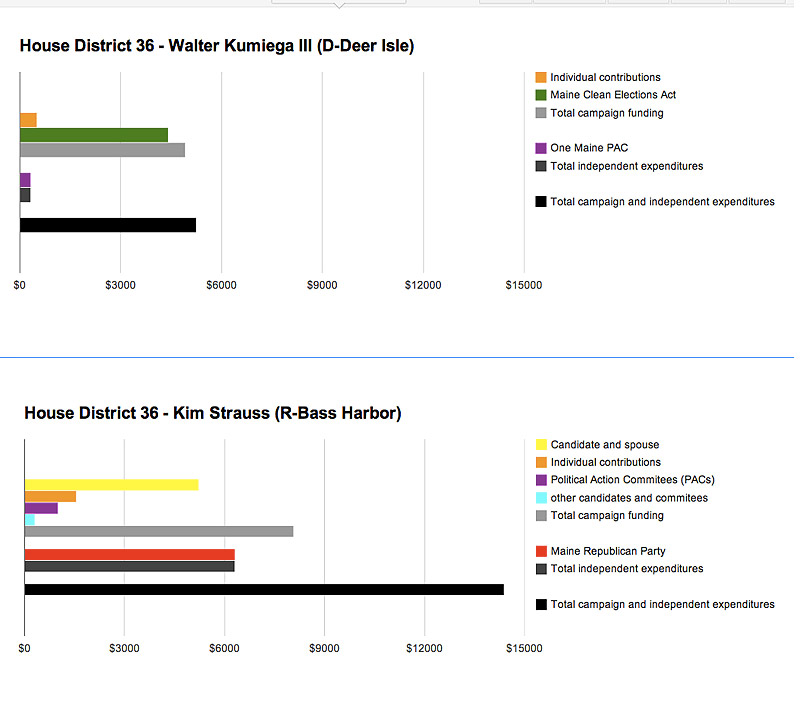

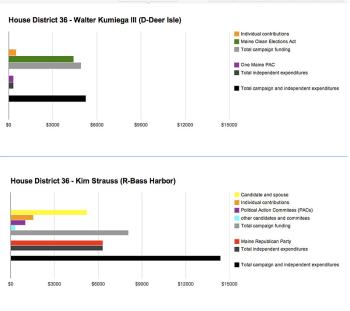

Challenger for the Maine House District 36 seat Kim Strauss (R-Bass Harbor) spent more of her own money than any other candidate in the region in her bid to defeat incumbent Rep. Walter Kumiega III (D-Deer Isle). Bass also got help from the Republican Party, while Kumiega used primarily MCEA funding. (Chart by Ethan Andrews

Challenger for the Maine House District 36 seat Kim Strauss (R-Bass Harbor) spent more of her own money than any other candidate in the region in her bid to defeat incumbent Rep. Walter Kumiega III (D-Deer Isle). Bass also got help from the Republican Party, while Kumiega used primarily MCEA funding. (Chart by Ethan Andrews

In Maine's Senate District 20 race, incumbent Leslie Fossel (R-Alna) raised more private campaign money, but challenger Christopher Johnson (D-Lincoln) had strong backing from the education and labor union PAC, The Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

In Maine's Senate District 20 race, incumbent Leslie Fossel (R-Alna) raised more private campaign money, but challenger Christopher Johnson (D-Lincoln) had strong backing from the education and labor union PAC, The Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Spending on each of the candidates in the Maine House District 45 race came from very different sources. Rep. Ryan Harmon's was notable for being the only privately-funded campaign in Waldo County. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Spending on each of the candidates in the Maine House District 45 race came from very different sources. Rep. Ryan Harmon's was notable for being the only privately-funded campaign in Waldo County. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

The sixth most expensive race in the state and most expensive in the Midcoast was the contest for Maine Senate District 22, in which both candidates attracted large amounts of spending by the political parties and outside PACs. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

The sixth most expensive race in the state and most expensive in the Midcoast was the contest for Maine Senate District 22, in which both candidates attracted large amounts of spending by the political parties and outside PACs. (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Campaign spending in the Maine House District 52 race between incumbent Rep. Deborah Sanderson (R-Chelsea) and Elizabeth Miller (D-Somerville). (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Campaign spending in the Maine House District 52 race between incumbent Rep. Deborah Sanderson (R-Chelsea) and Elizabeth Miller (D-Somerville). (Chart by Ethan Andrews)

Challenger for the Maine House District 36 seat Kim Strauss (R-Bass Harbor) spent more of her own money than any other candidate in the region in her bid to defeat incumbent Rep. Walter Kumiega III (D-Deer Isle). Bass also got help from the Republican Party, while Kumiega used primarily MCEA funding. (Chart by Ethan Andrews

Challenger for the Maine House District 36 seat Kim Strauss (R-Bass Harbor) spent more of her own money than any other candidate in the region in her bid to defeat incumbent Rep. Walter Kumiega III (D-Deer Isle). Bass also got help from the Republican Party, while Kumiega used primarily MCEA funding. (Chart by Ethan Andrews

MIDCOAST - Does money win elections in Maine? It's a broad question, so let's say "maybe." We've all heard of candidates who spent a personal fortune trying to get elected to only to lose. But those tales, if not apocryphal, must be the exception to the rule. And campaign money — whether privately raised, given through Maine's Clean Elections system or funneled through one of the roughly 200 party affiliated and political action committees registered with the Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices — is a time-tested engine of political races. No doubt.

A majority of candidates for state office this year ran under the provisions of the 1996 Maine Clean Elections Act. But the numbers have also dropped since a 2011 Supreme Court ruling in which provisions in Clean Elections laws that allowed for "triggered" funding was deemed unconstitutional. Previously a publicly-funded candidate would get additional money "triggered" by a privately-financed candidate reaching some fundraising threshold.

The case originated in Arizona, but with the Supreme Court decision Maine followed suit and set matching funds this year at fixed levels. The amount, according to Maine Ethics Commission Registrar Sandy Thompson, is calculated based on spending in the district in past years, and the candidates get it all in either June, or July if they enter the race late.

"That's what they get; that's what they live with," she said. "It doesn't matter how much the privately-funded candidate has raised anymore."

Thompson said the allocations in 2012 dropped by about 5-percent from 2010, and that those were down 5-percent from 2008.

Taken together, these restrictions and cuts would seem to favor big war chests of privately-funded candidates. A small example of this can be seen in the House District 36 race (pictured in the gallery at right), in which the campaign of privately-funded challenger Kim Strauss (R-Bass Harbor) benefitted from nearly three times as much money expended as the campaign by incumbent and Clean Elections candidate Rep. Walter Kumiega III.

But with MCEA amounts not pegged to private fundraising on either end, it's also not unusual for a Clean Elections candidate to end up with more money, as happened in House Districts 47 and 48 this year. The overall funding in these races was small, but the difference in the amounts available to each candidate was in the $1000s.

Because the money comes directly from the state, funding for Clean Elections is about as transparent as it gets. But from there it's often hard to tell who's paying for what.

The public disclosures of privately-funded candidates in Maine are one of the few sunlit spots left in the private financing system. Where else can you see that the Pharmaceutical giant Merck has given to the same campaign as the National Rifle Association and a self-employed musician named James Taylor? The disclosures might illuminate the candidate's leanings or connections, but in real money terms, they are often small compared with the influence of outside organizations.

In most races, the quaint interplay between campaign coffers (privately-funded or MCEA) is totally ecliped by expenditures from independent political entities — the PACs and the Super PACs, but to an equal degree the Democratic and Republican Party committees - that are ostensibly independent of the candidate they are supporting or opposing.

Outside of the major party committees, the labor union-financed Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class was by far the largest outside contributor to statehouse races in Midcoast districts.

House District 45 paired a well-financed, privately-funded incumbent, Ryan Harmon (R-Palermo), against an MCEA-funded challenger, Brian Jones (D-Freedom), who had less money in his campaign account but got substantial backing from his party and The Committee to Rebuild Maine's Middle Class in the form of independent expenditures. Depending upon how you look at it, the contribution from the PAC either kept the race from being a financial blow-out or undermined a wide-based fundraising effort with a few broad strokes. Either way, it made it a closer contest in financial terms.

Spending in District 45 and other Midcoast races where the distribution or scale of money was somehow noteable are broken down in the gallery images at right.

Senate Districts 20 (Lincoln County) and 22 (Knox County) stood out for the massive amounts of money contributed by outside groups, ranking number 7 and 6, respectively, among the top ten most expensive races in the state. Senate District 28 (Southern Hancock County) ranked number 9.

By contrast, the Senate District 23 (Waldo County) race was overlooked by the parties and PACs.

Like their counterparts in Knox County, both Waldo County's incumbent Sen. Michaeal Thibodeau (R-Winterport) and challenger Glenn "Chip" Curry (D-Belfast) ran Clean Elections. But where roughly $200,000 was poured into the District 22 race by outside groups, no outside expenditures were reported for District 23.

Several House races in Waldo County were the subject of unanswered outside spending for one candidate — or in opposition to the other (in the graphics of campaign spending at right, any money spent in opposition to one candidate is treated as support for the other).

The Maine Republican Party and the Washington DC-based Americans for Tax Reform collectively put over $12,000 behind House District 43 challenger Donna Hopkins (R-Belmont), while incumbent Rep. Erin Herbig (D-Belfast) received no support from outside groups. Both ran Clean Elections campaigns, but the overall spending skewed strongly in favor of Hopkins.

The case was similar in the District 41 race, where The Maine Democratic State Commitee along with several PACs spent over $13,000 in support of MCEA-funded challenger Meredith Ares (D-Searsport). Incumbent Rep. James Gillway (R-Searsport) was not the beneficiary of any outside spending and as of the most recent disclosures, had spent around $2,800 of his roughly $5,000 MCEA allotment.

Unenrolled House District 42 candidate Joe Brooks was the target of close to $4,000 in opposition spending by the Maine Republican Party, and his opponent Leo Lachance the recipient of a similar value of support from the party. Brooks did not receive outside funding. Both candidates ran Clean Elections campaigns.

So, did money make a difference in this election?

As always, "maybe."

Penobscot Bay Pilot reporter Ethan Andrews can be reached at ethanandrews@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States