Across the country, older men are dying at higher rates of gun suicide. Here’s what that looks like in Maine.

This story was published by The Maine Monitor in partnership with The Trace’s Gun Violence Data Hub. It includes data and details about firearm suicides that may disturb some readers. Please remember that help is available.

Sue Mackey Andrews moved to rural Piscataquis County in search of a close-knit community, small schools and beautiful scenery. But in the nearly five decades she’s lived there, life has gotten harder, manifesting in devastating ways.

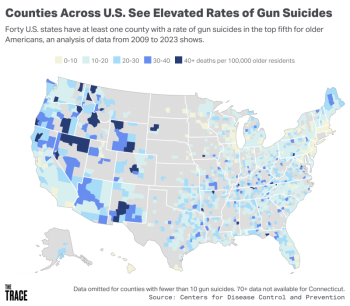

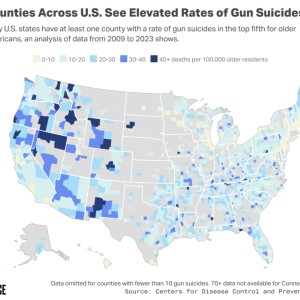

Between 2009 and 2023, Piscataquis County had a higher rate of gun suicides among adults 70 and older than 97 percent of all counties in the United States, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data analyzed by The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom that reports on gun violence. It’s a small county, with just 17,000 residents, which means 16 deaths translates to a rate of 38 per 100,000 older individuals.

It’s a hard-hit region in a hard-hit state: More older Mainers died by gun suicide than they did in car crashes over that period. The overall gun suicide rate in Maine was 16 per 100,000. The numbers represent a troubling trend playing out in rural communities across the country, where older adults, particularly white men, are dying at higher rates of gun suicide than any other group.

The vast majority of firearm deaths in Maine are suicides, according to state data. Guns are the most fatal method of suicide, and older adults are more likely to die from self-inflicted injuries.

In New England, only Vermont had a higher rate of gun suicides — and just slightly.

To Andrews, who works for a Piscataquis County nonprofit called Helping Hands with Heart, the high rate of gun suicides is evidence of how the social and economic fabric in her region has unraveled in recent decades. In 2007, Moosehead Manufacturing Company closed its furniture factory at the Mayo Mill in downtown Dover-Foxcroft, and laid off 120 workers.

Practically overnight, the 163-year-old mill, an economic cornerstone of the county, disappeared. Local communities are still reeling from the loss, Andrews said.

Today, Piscataquis County has one of the highest poverty rates in the state. It has the oldest population in the state, with 15 percent of older residents living below the poverty line.

There are no state offices in the county and limited access to medical care, meaning most people have to drive an hour-plus to Bangor for everything from a driver’s license to cancer treatment.

“We’re the oldest, poorest and sickest county in the state,” Andrews said. “And we’re just getting older, sicker and poorer.”

Piscataquis is one of a handful of “frontier” counties east of the Mississippi, meaning it has six or fewer people per square mile, according to the Rural Health Information Hub.

And for older residents, many of whom may not have family nearby, have poor internet connectivity, limited mobility or preexisting medical conditions, the fallout can be fatal, said Dr. Tony Ng, a psychiatrist and the medical director for community services at Northern Light Acadia Hospital.

Several studies have shown that easy access to guns is associated with higher suicide risk. Gun ownership tends to be highest in older, white, conservative and rural areas like Piscataquis County, according to the Pew Research Center.

“Social isolation, physical illnesses, lack of social support really kind of increase the risk (of suicide) compared to your middle-aged, younger person,” Ng said.

Bob Young, the Piscataquis County sheriff, said that almost every older adult he’s known of that died by suicide had a medical issue, like a terminal illness.

“We have a high population of elderly and have consistently for as long as I’ve been around here. But with that, many of the elderly find themselves alone. Their families have moved away,” Young said. “They’re in very rural areas, so they tend not to go out much. Resources are very scarce in rural areas and so I think there’s often that sense of isolation.”

While research into the link between a terminal illness and suicide is limited, a 2023 study found that three-quarters of older adults who died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound had a physical health issue.

One of the big issues Andrews sees is that people are reluctant to ask for help.

In her work, she has encountered people living in tough circumstances, some in trailers with no running water or electricity. And although there are organizations, like the one she works for, available to help them get to doctor’s appointments or pay rent, many don’t reach out until they’re already in deep trouble.

“By then, they’re getting evicted from their apartment or their house. By then, you know, their car won’t run at all. So the repair costs are four times what they would have been had they called in the beginning,” she said.

Young said he sees something similar.

“It’s not that they don’t think they need help,” he said. “They don’t want to bother people.”

This means mental health crises among older people tend to stay hidden. The local emergency room in Dover-Foxcroft has seen more and more younger people in crisis coming to the hospital, said William Sheppard, a physician associate at Northern Light Mayo Hospital, but not as many older adults.

A Monitor analysis of yellow flag orders — the process by which a law enforcement officer can remove weapons from a person they deem at risk of harm to themselves or others — shows that nearly half of all completed orders were for individuals between 20 and 39 years old. Less than a tenth of completed orders were for individuals 70 years and older. Law enforcement cited a person’s suicidal intent in the majority of all orders.

The data stretches from July 2020, when Maine’s yellow flag law went into effect, to late September 2025. Its use went up significantly after the 2023 mass shooting in Lewiston.

Some advocates of stricter gun laws want Maine to adopt a red flag law, which would allow family or household members, in addition to law enforcement, to directly petition a court to temporarily remove weapons from someone they think is at risk. The question is going before Maine voters this November.

“Extreme risk protection orders are better suited to reducing suicide because family and household members are usually the first people to know when someone is at a crisis level that could lead to suicide,” said Nacole Palmer, the executive director of the Maine Gun Safety Coalition, the sponsor organization behind the Safe Schools, Safe Communities initiative, which successfully petitioned to put the question on the ballot.

The current yellow flag law, which requires an evaluation and endorsement from a behavioral health practitioner before an order can get approval from a judge, doesn’t allow family members to immediately “take action when they’re really, really concerned about their loved ones,” Palmer said.

Jack Sorensen, the spokesperson for Safe Schools, Safe Communities, said a red flag law and a 72-hour waiting period on gun purchases are critical means of intervention for gun suicides.

“Suicide is an impulsive act. An impulsive act committed by other means can potentially be reversible and someone can get the help they need,” he said. “But it is almost never the case when a firearm is involved.”

State legislators passed a waiting period law last year, requiring that a seller wait three days after a sale of a firearm to transfer ownership to a purchaser. Months after it went into effect, gun rights groups filed a lawsuit challenging the waiting period’s constitutionality. A federal judge suspended the law in February, and that decision was then appealed. An appellate judge has yet to issue a ruling.

Palmer said the 72 hours offers a reprieve, tempering the impulse and keeping a lethal weapon out of a person in crisis’s hands.

Interruption is one of the most effective tools to reduce suicide, Sorensen added.

“Just interrupting the event and delaying it is one of the most important things you can do,” he said, “even if it’s an hour.”

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call 911.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text the free, confidential, 24/7 Maine Crisis Line at 1-888-568-1112 for immediate assistance.

To reach the national Suicide Crisis Lifeline, call or text 988, or go to 988lifeline.org, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

For additional, non-emergent assistance, call the 24/7 Maine Intentional Warm Line at 1-866-771-9276. The NAMI Maine Help Line is available Monday-Friday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. and can be reached by calling 1-800-464-5767 or emailing helpline@namimaine.org. For additional information, visit NAMI Maine’s resource database.

Data Methodology: This story was reported using data from The Trace’s Gun Violence Data Hub that was included in a recent story co-published with GQ. Using the most recent mortality data from the CDC, which is current through 2023, The Trace and GQ calculated per capita gun suicide rates in the 70 and older population for every U.S. county. A time frame of 15 years surfaced geographic areas that would be omitted from looking at one, five, or even 10 years of data, because the CDC requires suppression to protect the privacy of people in any subgroup with fewer than 10 deaths. The same data helped determine rates among different demographics, including race, ethnicity, and sex. Classifications from the National Center for Health Statistics guided labeling of geographies as urban, rural, etc. — a method used in past reporting by The Trace.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor, a nonprofit civic news organization. To get regular coverage from The Monitor, sign up for a free Monitor newsletter here.