Eva Murray: 350 dot Rockland… and many ruminations on small efforts

On Monday, Aug. 26, I happened to be in Rockland overnight, basically because the dump wasn’t open that day. At about 3 p.m. I drove off the ferry vessel Everett Libby with a ton and a quarter of this island’s corrugated cardboard, plastic containers and one kaput toilet in a rented Budget box truck, that being our usual “garbage truck.” The recycling facility to which I’d haul this material wouldn’t be open until Tuesday morning; for the evening, I could enjoy the cultural highlights of the big city.

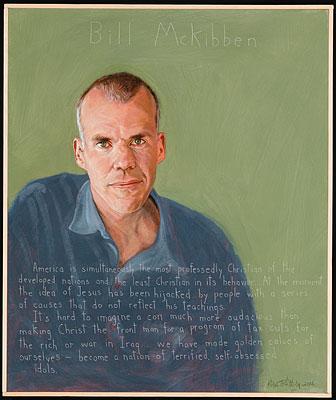

I happened onto an event at the Strand Theater. Do the Math, a short documentary film about 350.org and the efforts of writer and climate-change activist Bill McKibben and others was being shown, followed by a few local speakers, an “ice cream social” at intermission, and musical offerings by David Dodson, David Mallett, and John and Rachel Nicholas. I hadn’t heard the last two before but Dodson and Mallett are always good fun, and the subject interests me. Besides, I’ve met Bill McKIbben. His brother taught school on Matinicus right after I did, and married a Matinicus native; 350.org is close to home.

In Do the Math, we are reminded of three important numbers. A great many scientists and governments worldwide agree that TWO degrees C. is the maximum increase in global average temperature that our civilization as it exists now can absorb. Beyond that, radical change to the planet — and to our lifestyles — becomes inevitable. To remain below that limit we must emit no more than another 565 gigatonnes (metric tons) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere worldwide. Now, for the third number, we are told that the fossil fuel industry has 2,795 gigatonnes of CO2 in reserve right now.

Hearing those numbers I, for one — sitting by myself in an old-fashioned movie theater in Rockland, Maine, wondering what kind of ice cream they’d be serving and hoping that the musicians wouldn’t sing anything that would make me cr y— felt a bit helpless.

Let’s set aside the digging into where these numbers came from. I agree that we ought to understand the background of any statistics we quote, but my own querying can be discussed at another time. As for the question of whether “human-caused climate change” is even a real issue, I remain convinced. You may stop reading now if you think I’ve been suckered, but I don’t see what anybody would have to gain by making this stuff up. Like I said, I know McKibben, I know his family. I have no reason to think he’s got anything to gain by stringing us along.

So in the face of a change to all of civilization as we know it — for that is what we’re talking about — are any of our tiny individual efforts going to make a difference? Does offering a few islanders a better alternative than the backyard burn barrels of the old days matter? Our island recycling program is a small thing, indeed, a very small thing. I think it does a little to improve the air quality in this tiny town, but it isn’t going to change the chemical imbalance of the planet’s atmosphere in general.

Will my own wobbly and imprecise attempts at fuel conservation help at all?

“The fishermen know,” said Judith Lawson, in her introduction to the documentary on Monday. “The fishermen and the farmers know this is real.”

My neighbors are all fishermen. It is possible that they all know, but most aren’t so sure our own actions matter.

Sitting there, surrounded by people who wanted to save the planet, I felt as though we were being exhorted to go out and stop soft-coal power plants, stop the burning down of Indonesia and Brazil, hell, stop the industrial revolution by the strength of our own hands. What to do? I worried that maybe we were patting ourselves on the backs too much for buying local bacon or insulating our attics when the realities are so much bigger.

The scale of this whole problem is beyond my ken, to be honest. In the film and at his public appearances, McKibben explains how the largest oil companies are “rogue companies” now, writing their own regulations and quite unlike the rest of us in terms of rules and consequences. They are not subject to the same pollution rules as any man who tosses his coffee cup in the street. They unlike anybody else, says McKibben, may dump their waste in the public space for free.

Really.

Some important ideas were discussed at the Rockland event. Significant among them was the suggestion that we divest, meaning remove our investments from fossil fuel stocks. This has especially to do with mutual funds, often retirement funds, and with college endowments. It may take a good deal of digging to find out what your retirement is invested in, should you be lucky enough to have one. But anybody can vote with their money as we make decisions about what to purchase, or so we say. Consider that sometimes even that is easier said than done. Not every American has the diverse food and other shopping choices that we have in Rockland.

More ideas that came up in the conversation: we can get those solar panels up and going. We can promise to engage in civil disobedience if the President approves the Keystone pipeline. We can power our houses down for an hour a day (or night). I like this last one. It smacks of “meatless Tuesday,” an austerity many of us only learned about from Bugs Bunny, but it does sound do-able without initial investment or lengthy research or a trip out of state, at least for those who own their home. Why not? Throw the main breaker. (That sounds like the British navy-ism “splice the main brace;” we can all dump the electricity and have a drink of rum in the dark beside the breaker box. OK, maybe not there.) I mention this with the knowledge that my neighbors may wince; I have the keys to this island’s power station and I know how to kill the whole thing. Don’t worry; I know my place (heh heh).

We could easily modify this list of actions by adding “just do whichever you can —you don’t have to do them all,” but that take-it-easy attitude was not the sense I got at the event Monday evening. Maybe we really must do them all. The argument sure sounded like we don’t have time to mess around with namby-pamby, feel –good, half-way measures. The prevailing sentiment was that we need to get out there and fight. The Strand was filled with the most earnest of citizens, many expressing willingness to go get arrested in front of the White House wearing suit and tie in order to protest the Keystone XL pipeline or anything else that endangers, well, civilization as we know it. These folks mean business.

A lot was said Monday night in the Strand Theater about “preaching to the choir.” I looked around at my fellow audience members: no makeup on the women, and the men mostly skinny fellows in sandals. A striking majority were clearly retirement age. “This,” I had to admit, “is not exactly a cross-section of the demographic.” This was a subculture and we knew it. We were already recycling, driving efficient cars, and bicycling, and turning down the heat. A few mutterings: perhaps the other people were all up at Walmart. How unfair! What an idea! What a stereotype! Walmart did come up a lot, though. Later that night, as I sat with my pint of draft and my certifiably inorganic snack in a restaurant beside my hotel, I see that the sign for the new Thomaston Walmart has been delivered. Presumably the old Walmart wasn’t big enough.

I have friends among the purists, honorable souls nearly bordering on the intolerable with their conscientious baggie-washing, their mason-jar cozies and their vegan skinniness and their transportation freeloading. I can get pretty excessive about certain things myself; I am annoyingly gung-ho about using both sides of a piece of paper and using cardboard boxes over and over. I am a trash geek and a repairer of socks and one of those people who reacts with personally affront when some driver tosses her cigarette out the car window. But I am also part of the problem, let there be no mistake.

Dave Mallett sang and I considered my own little row of beans. He sang “Fat of the Land” and I thought of my Yukon Golds, so sweet, and the little russets we fried up the other day. A little backyard garden is sacred agriculture, and good for the mental health, and I feel the blessings and sentimentality and the peace and quiet, but I am just a hobby gardener. In summer I have too little time to do a nice job and too little interest in squash and cabbage to live all winter from my labors. McKibben and others urge us to learn to grow food, because the future may require it. I wonder, though, does a little bit matter? Does the satisfaction of a few new potatoes or a winter’s supply of home-grown garlic even register at all, or does sincerity here demand a total self-sufficiency? Is an effort discredited when it is a mere hobby — must we sweat hard for it to count? I have the skills, not to mention the hand tools and the mason jars, but I am not using them much lately. Am I selling out?

Despite our use-it-up-or-wear-it-out Yankee housekeeping and our organic string bean patch, my household also burns anthracite coal on the coldest winter nights to keep things going until morning, and I use bituminous coal in the blacksmith shop to make hand-forged ironware. We rely on the kerosene heater when I’m not home to stoke the stove all day; it’ll keep the pipes from freezing. We live where transportation of all sorts is heavy and expensive. I fly in airplanes; in fact, someday I will say “I fly airplanes,” and that is acknowledged to be a hugely energy-intensive mode of travel (those who study such things probably have never seen a lobster boat race).

What can we do? What can any one person do? Can I, me, myself do anything to make a difference? Can anybody, really, aside from the guys who run Exxon Mobil and, uh, China? Is chaining ourselves to a fence in protest the only real way to fight back against this tidal wave of pollution? If I make a list of my errands and plot a map to make my circuit through Rockland more efficient, so as to minimize excess driving and save on fuel, am I just being silly?

We heard from local people who are doing what they can. We heard from 9-year-old Thor who stood on a box to deliver some extremely articulate observations. We heard from one of the two Maine Maritime Academy students who have purchased and are running the Goose River Hydroelectric Company in Belfast. We heard the words of the poet Rumi, which to my ears offered a timely reassurance: “You have broken your vows a thousand times — come, come again.” We need to hear this reassurance, we with our small efforts that may or may not help, we with our conflicting economies and our cheap-product, save-a-penny upbringings and our petroleum-heavy realities. We need to hear that it’s legit to keep starting over, even if we know we have taken the easy road before.

The whole concern forces us to look at the ethics of our housekeeping, our money and our day-to-day lives. This is strong medicine and I for one am not sure how to do enough. I admire those who are strident and committed, but I eat on the road and I buy a lot of gasoline… and I burn coal. In the documentary we hear the words of attorney and activist Van Jones who says, “When you know what’s evil — now, if you’re ignorant you get a pass, but if you know what’s evi l— you are morally obligated to withhold your energy from it.”

Toward the end of the evening Dave Mallet sang “Ten Men in Black Hats,” conjuring up a scenario where ten gangster-like tycoons divide up control of all of the world’s major resources:

One man got the silver, one man got the gold,

One said, “I don’t want nothin’, I just don’t never want to grow old.”

One said, “I get the water, they need it everywhere,”

One said, “I get all them messages people send out through the air.”

They divvied up the green grass, they divvied up the soil,

One man got all the iron ore and one man got all the oil.

One said, “I get the people, they all work for me!”

And another, his little brother, said, “I get all the fishes in the sea.”

Ten men in black hats, with their faces cold and hard,

Said, “This is good for everyone. Somebody’s got to take charge.”

Then they all lit their stogies, and tipped back in their chairs;

Ten men in black hats--are you sure you wasn’t there? (David Mallet, with permission)

A few of us are asking ourselves, “Was I there?”

350.org takes its name from the determination by climate scientists that 350 parts per million is the maximum carbon dioxide load our atmosphere can handle before significant and troubling changes are experienced. Presently, we're approaching 400 ppm.

Eva Murray lives on Matinicus.

More Industrial Arts

In the middle of the bay

A system that makes it hard on people who want to do the right thing