Knox County, Rockland well involved in Restorative Justice; demand outnumbers supply

ROCKLAND — In the past year, a few cases involving juveniles painting swastikas in Rockland and in Camden have occurred. Through their assigned restorative justice programs, the offenders were put on a Zoom call with a Holocaust survivor who lives in Maryland.

“It was a very, very emotional and telling conversation,” said retired attorney Ed Modell, who has been volunteering with Restorative Justice Maine for three years.

One of the juveniles had started the program with a resolute position that he wasn’t going to take responsibility for the graffiti. After the call, he wrote an apology letter to the Jewish community of Rockland.

Monday, Feb. 7, 2022, the Rockland Police Review Committee hosted an online forum with the Restorative Justice team that represents five local counties in this area. The Committee asked how to get Rockland police involved with Restorative Justice Maine.

The answer, according to RJP, Waldo County Sheriff’s Office’s Chief Deputy Jason Trundy, and the Rockland PD, is that Rockland is already involved. It’s just not visible since Rockland doesn’t have many juvenile arrests, according to Joel Neal, of the Rockland PD.

Restorative Justice is for both juveniles and adults. However, as was mentioned during the forum, people tend to get more involved when it’s a case involving a juvenile. Waldo County’s RJP concerns also include the opioid crisis, substance abuse, mental illness, conflict, and homelessness.

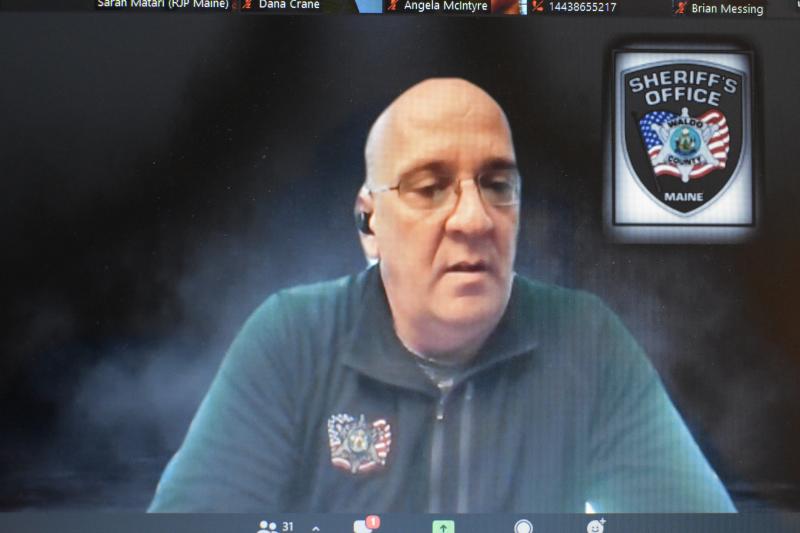

While Waldo County Sheriff’s Office, and Trundy himself, initiated a Midcoast law enforcement relationship with RJP, Knox County Sheriff Tim Carroll co-wrote the initial grant application for state funding.

They partnered with Restorative Justice to provide conflict resolution. And they also partnered with an organization dealing with case management services. That organization only stayed with the program for the first year. Since then, Waldo County has worked with Volunteers of America.

And now, Knox County is known as the biggest source of referrals to the program.

On any given day, most of the counties included with the local program – Waldo, Sagadahoc, Lincoln, and Hancock – send five to six cases or referrals, according to Kathy Durgin-Leighton, executive director of Restorative Justice Maine.

Knox County averages 18 – 19 daily, most of which come from either the District Attorney’s office or the juvenile division of the Department of Corrections.

The Law Enforcement Assistant Divergence program might steer low-level offenders toward treatment and away from incarceration, but the program isn’t easy, according to Trundy.

“It is a lot more difficult for an offender to go through the restorative justice process [than the criminal court system] because they do have to admit their guilt,” he said. “Not only do they have to admit their guilt, they have to get in the circle with the people they harmed, and they have to hear how they harmed other people. They have to be accountable for that, and they have to be a part of a process to say ‘how am I going to heal that?’”

Many people cannot admit the guilt.

“Truth be told, if someone’s not willing to sit in there, not willing to participate, and not willing to engage, then they are going to defeat the process right out of the gate,” said Trundy. “So there is some very important criteria that has to be met to know that this process is going to do what it is intended to do.”

Each restorative justice program makes its own policies depending on funding, volunteers, and local needs.

Though Knox and Waldo sheriffs collaborated on the initial grants, each wrote individual policies.

For Waldo, some crimes are automatic exclusions to the program, such as sex offenses, domestic violence, or other specific violent crimes that cannot be diverted. And there are victims who won’t allow the offender the opportunity for divergence.

“It is very important to me, considering that the victims are the impacted individuals, that they have a voice in what does happens with the case that they are involved in,” said Trundy.

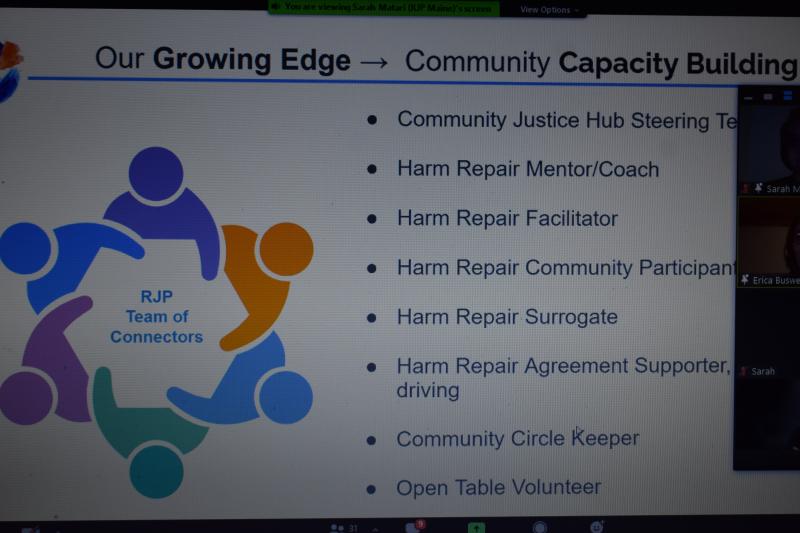

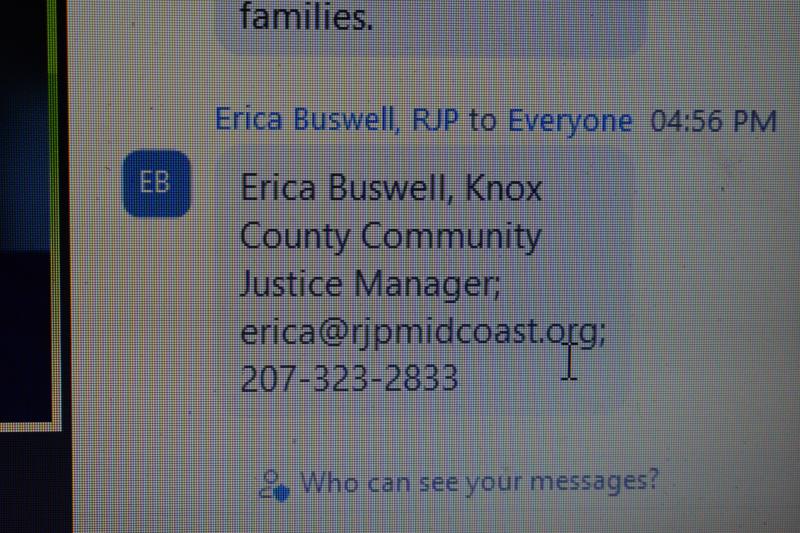

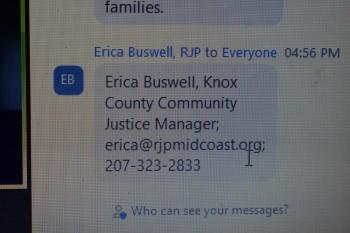

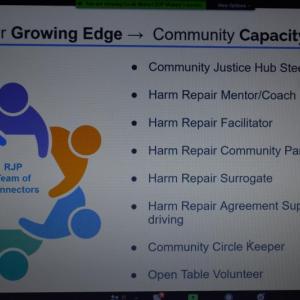

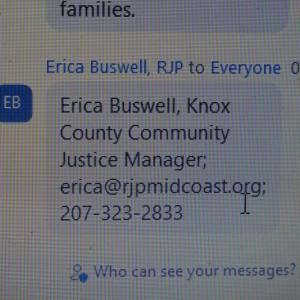

Ultimately, though, RJP is reliant on volunteers and staff. Currently, the program has one full-time person for each of Knox and Waldo counties. The other three counties each have a part-time person. The need is great, and RJP is looking for more help. They currently offer training on a donation basis. Also there are currently two courses provided through UMaine per year.

“I have no doubt that we could get more referrals from the Rockland Police Department, from other police departments within Knox County,” said Durgin-Leighton. “Right now we wouldn’t have the capacity to address more referrals, just because of where we are right now. We’re constantly trying to train new volunteers. We’re bringing in the Community Justice hub in the Rockland office. We are expanding, but we want to do it in a way that we can provide quality over quantity.”

Sarah Matari, of RJP, did the same Restorative Justice-type work out of state before moving here five years ago.

“Maine is incredible,” she said. “It is light years ahead of New York City. You all have been doing great work here long before I, and others, got here.”

In the meantime, the Police Review Committee, and the Rockland community are asked by RJP to ponder the following questions: ‘What is the community’s perception of safety, what is the community’s perception of belonging, and where does the community think the resources are for conflict resolution?’

‘Can we as a community look at what’s happening in terms of crime in the community, if we understand what our community is thinking regarding their sense of wellbeing, whether or not they feel safe, whether they feel a sense of belonging, and how they are responding to conflict?’

Reach Sarah Thompson at news@penbaypilot.com