The year without a summer

Harbour Mitchell examining a six-foot deep cellar hole at Merryspring Nature Center (Photo courtesy Merryspring Nature Center)

Harbour Mitchell examining a six-foot deep cellar hole at Merryspring Nature Center (Photo courtesy Merryspring Nature Center)

Harbour Mitchell, Union archeologist, and Merryspring’s Nature Center’s Program Director Brett Willard take a look at the latest findings from an old settlement in May 2018. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Harbour Mitchell, Union archeologist, and Merryspring’s Nature Center’s Program Director Brett Willard take a look at the latest findings from an old settlement in May 2018. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

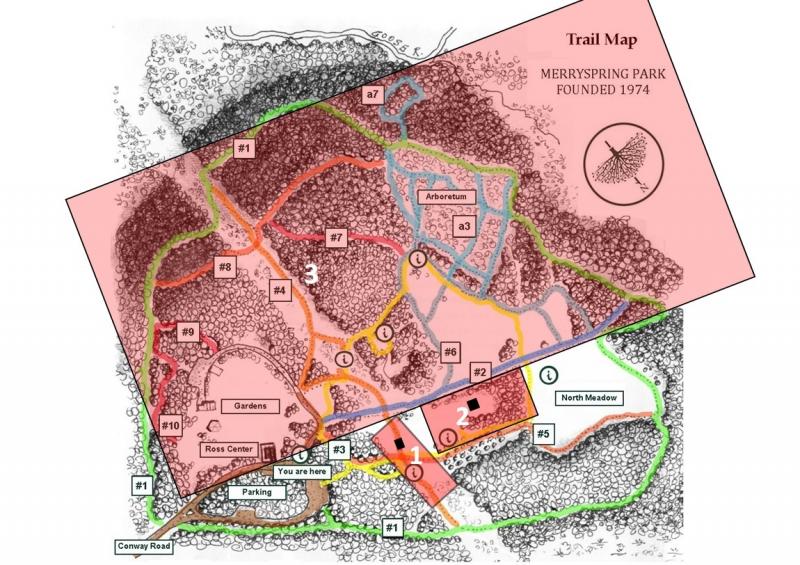

Map courtesy Merryspring Nature Center

Map courtesy Merryspring Nature Center

A sample of the clam shells excavated from the Hosmer farm site. (Photo courtesy Harbour Mitchell)

A sample of the clam shells excavated from the Hosmer farm site. (Photo courtesy Harbour Mitchell)

Harbour Mitchell examining a six-foot deep cellar hole at Merryspring Nature Center (Photo courtesy Merryspring Nature Center)

Harbour Mitchell examining a six-foot deep cellar hole at Merryspring Nature Center (Photo courtesy Merryspring Nature Center)

Harbour Mitchell, Union archeologist, and Merryspring’s Nature Center’s Program Director Brett Willard take a look at the latest findings from an old settlement in May 2018. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Harbour Mitchell, Union archeologist, and Merryspring’s Nature Center’s Program Director Brett Willard take a look at the latest findings from an old settlement in May 2018. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Map courtesy Merryspring Nature Center

Map courtesy Merryspring Nature Center

A sample of the clam shells excavated from the Hosmer farm site. (Photo courtesy Harbour Mitchell)

A sample of the clam shells excavated from the Hosmer farm site. (Photo courtesy Harbour Mitchell)

A lot can be learned from digging up people’s trash, said local archeologist Harbour Mitchell, who did a six-month dig at Merryspring Nature Center in 2018. Merryspring, in Camden at the end of Conway Road, was once the site of the Asa Hosmer farm, with a large, two-story, Federal-style farmhouse built circa 1800 by an unknown person or people, before Hosmer bought it. But in less than 20 years, all of the farmhouse occupants would be gone, the home abandoned.

Based on all of his findings and research, this is likely what happened.

“The year of no summer, we’re in a post-Revolutionary War period,” recalled Mitchell, setting the scene. “There are militias, but little law enforcement, and little to no governmental rules or regulations. People are living in an unrestricted place.”

Having worked for the University of Maine, Maine Historic Preservation Commission in Augusta, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, and as a professional research archaeologist throughout the region, Mitchell put together a piece of the puzzle at the Merryspring site to explain what happened after the war. According to Mitchell’s archeological summary:

While the War of 1812 no doubt took a toll on the new farm’s occupants, and made economic sustainability tenuous, the coup de grâce was likely the so called “year without a summer” — 1816. Global cooling, resulting from the eruption of Mount Tambora, in Indonesia in 1815, caused massive die-offs of vegetative and flowering fruits, grains and other necessary crops. Throughout Maine and the broader region, in 1816, every month saw frost, and snow fell in July.

“It is the single largest volcanic eruption in historic memory,” he said. “Of course, the people living there can’t see what’s coming. They could not have known what caused the global cooling, but that climactic response cooled the globe a half a degree and changed the seasons. If I were to animate this for you: The normal cycle, the birds, the bees, the pollination, the trees, and crops, are no longer normal. Every month had frost in 1816. No trees produced fruit or maple sugar. Hay was stunted. The farmers living at the Hosmer Farm site might have gotten one hay cutting in an entire summer into fall, whereas in a good season you’d get two or three cuttings. They made it through the summer and winter of 1816 with enough food from butchering their animals. But, by 1817, people were in desperate straits. A clam shell dump at the Hosmer Farm site suggests the occupants walked miles to and from the local clam flats and subsisted to a significant degree on clams to get by.”

Based on his excavations at the Hosmer Farm site at Merryspring, and the Philip Ulmer site, near Tanglewood, in Lincolnville, clams were likely a significant percentage of the locally available food supply for several years.

Imagine little more than a diet of clams on which to survive. Back in the days when prisoners protested for being fed lobsters three times a week, here you have people virtually imprisoned by Nature refusing to dole out its seasonal bounty.

There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that anyone ever came back after 1820, or lived on the Hosmer farm, ever again. What was once a vision of the future now sat abandoned, a testimony only to what might have been.

Visit Merryspring Nature Center this summer to go look at the site where the old Asa Hosmer farmhouse once stood and let yourself glide back to the past.

Event Date

Address

United States