The return of the white shark to Maine waters

What else does 2020 have in store for Mainers? The browntail moth rash, ticks, Lyme Disease, a pandemic...and now you can add great white sharks to the mix.

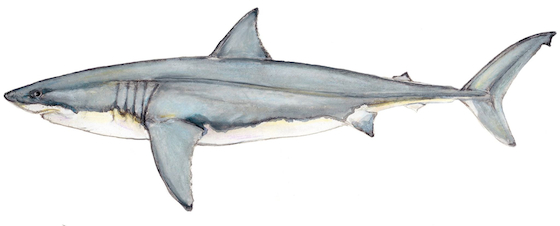

Award-winning journalist Ret Talbot gave a Zoom talk last week on the return of the white shark to New England (see embedded video). As a science writer who covers fisheries and ocean issues, he has spent the last year researching the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). After Maine’s first recorded shark attack fatality in July, there has been a renewed public interest over this predator, which has roamed New England waters for thousands of years.

While Talbot understands the fear and fascination over the tragedy and wanted to convey respect toward the woman’s family, he didn’t want to focus on that angle for his talk. Instead, he wanted to highlight the fact that the increased white shark presence in Maine waters is actually a conservation success story.

“It is remarkable to have an apex predator return to an ecosystem in larger numbers,” he said. “It’s not something we see all that often.”

A mistaken conception about why white sharks are appearing in higher numbers in New England waters has been attributed to global warming and ocean temperatures rising, but in fact, according to Talbot, and other shark experts, it is the causal relationship between two simultaneous factors.

Jaws didn’t help matters

“People have always hunted sharks, but we know during the ‘70s and ‘80s, shark populations declined due to commercial fishing. And yes, the movie made it acceptable to go out and kill this ‘monster.’”

Ret Talbot

In 1972, Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) which prohibits humans from hunting and killing seals.

“In 1973, a census of gray seals on the coast of Maine found something like 30 animals total,” said Talbot. “Today, their population has swelled into the tens of thousands.”

Then, in 1997, due to a decline in sharks in U.S. waters, the National Marine Fisheries Service banned the killing of five species of sharks, including white sharks, allowing their populations to swell, as well.

“The ban on killing sharks combined with the ban on killing their preferred prey contributed to this resurgence,” he said.

If it happened once, can it happen again?

A shark attack is extremely rare, according to numerous scientists who have equated its occurrence on par with getting struck by lightning.

“Depending upon whom you talk to, there have been 12 unprovoked shark attacks in Massachusetts between 1724 and 2018 and if you break that down, six of those attacks occurred between 1724 and 1965,” said Talbot. “But, if you look at the data between 2012 and 2018, that’s six recorded attacks in just seven years with the most recent fatality, the first in more than 80 years, in 2018. There have only been three recorded unprovoked shark attacks in Massachusetts.”

Talbot was careful to say some of the evidence he has researched is anecdotal, “but it does suggest that there may be an abundance of white sharks in the northwest Atlantic is on the rise,” he said. “And that is certainly borne out by the anecdotes and the data that researchers are still in the process of collecting.”

“We’re going to have a lot more data soon,” he continued. “The state has partnered with the Department of Maine Fisheries in Massachusetts to connect their research with Maine researchers. By tagging sharks, they will be able to track sharks into Maine waters. At least 20 percent of the sharks that are showing up on the outer Cape are making their way north to Maine.”

Talbot clarified that this data is not an immediate cause for alarm.

“I think it’s important to point out that the majority of unprovoked attacks are usually the case of ‘mistaken identity.’” he said. This tracks with this incident in Maine, whereby the victim was wearing a black wetsuit when attacked. Sharks have poor eyesight and officials surmised the attack occurred because the swimmer resembled a seal on the surface of the water.

“When we have more data about their predatory behaviors, it will help public safety officials forecast when and how they are attacking their prey and how better to avoid them,” he said.

To learn more about Talbot’s work, blog, and upcoming speaking events, visit www.rettalbot.com

Kay Stephens can be reached at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

United States