Kelp farming is a win-win when it comes to healing the ocean

Seaweed, for Karen Cooper, a lobsterman on North Haven, was never anything special. Like a roadside weed, it was everywhere. The brown, rubbery-looking vegetation only had one purpose — to provide cover for lobsters, crab, sea urchins and fish.Then, something happened that changed the way she saw seaweed.

“More than five years ago, my best friend got breast cancer,” she said. “And one of things she did is to go on a raw macrobiotic diet. She was eating seaweed salad one day and I was like ‘Oh my God, what the heck is that?’ It was like green spaghetti.”

Cooper had grown up on an island surrounded by sugar kelp and rockweed, but it sure didn’t look like this salad.

“There’s so many different varieties of seaweed,” she said. “So, I tried this seaweed salad and I realized it was quite delicious. And it’s obviously good for you.That’s why my friend was eating it to try and heal herself.”

That got Cooper’s wheels turning.

“I’d do anything for her, she was my best friend,” she said. “So, I looked it up online and found out who was already growing seaweed in Maine.”

Wild kelp harvesting along the estuaries and inlets of Maine’s “coastal highway” is nothing new. Asian and Native American civilizations have done it for centuries and several Maine businesses have been selling sea vegetables for decades. But, as Cooper would soon discover, the nation’s first commercial kelp farm called Ocean Approved started in Maine in 2009 in Casco Bay. Founded by Tollef Olson and Paul Dobbins, this farm has revolutionized how people are using and eating kelp, positioning Maine as a leader in the seaweed industry — and inspiring others up and down the coast to apply for their aquaculture lease, so they too, can harvest, process and sell it.

Cooper reached out to Dobbins, who sent her a “big, huge 300-page” manual on how to get started.

“I just about died,” she said. “But, last year, I sat in on a couple of seaweed talks at Maine Fishermen’s Forum. And they were showing us how to set up an aquaculture business around sugar kelp, all these things I thought I couldn’t do.”

Turns out Cooper was looking for help at the exact time that the Island Institute, in Rockland, was advertising for its new Aquaculture Business Development Program. And in Maine’s seaweed industry, it became six degrees of separation to connect everyone.

Susie Arnold, a marine scientist at the Island Institute, had been focusing on ocean acidification for the last three years.

“Maine is at a particular risk for ocean acidification for a variety of environmental and socio-economic reasons,” she said.

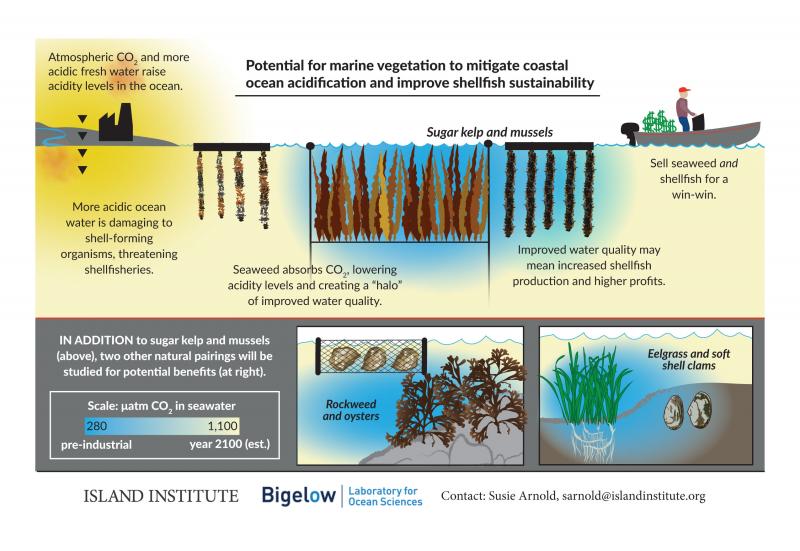

As a result, they ordered a study commission on what to do about it. One of the recommendations was to research if seaweed can play a role in remediating ocean acidification.

“Basically, marine plants like kelp photosynthesize like land plants, taking CO2 out of the environment and into their tissue,” Arnold said. “The theory is that when harvested, by taking that plant out of the water, you’re taking out the CO2, restoring the Ph balance in the water. And, you get the double benefit of harvesting the edible seaweed as a nutritious sea vegetable.”

This winter, Arnold teamed up with Nichole Price, from Bigelow Laboratories and Ocean Sciences, to deploy sophisticated instrumentation inside and just upstream of Ocean Approved’s kelp farm and test if the growing kelp was improving the water chemistry. Dobbins seeded the lines with almost microscopic kelp in early November. By January, the kelp was 14 inches long. By May or June, Arnold predicts, the kelp will be 14 or 15 feet long when it is harvested.

“Four days ago, we went out and collected the first set of data,” said Arnold. “What we've seen already is lower carbon dioxide inside Dobbins’ kelp farm waters than upstream at the control site.”

She’s excited that the theory is working, but is careful not to project too much at this point.

“This is preliminary and will have more data as the winter goes on,” she said. “But if this works, and we are able to demonstrate that kelp farming can remediate ocean acidification in the localized areas, it means promising things for shellfish aquaculture.”

Already, the Department of Marine Resources is working with a number of applications to develop more kelp farms that are co-located with and mussel and oyster farms.

Cooper didn’t realize it at the time, but over the last few years, kelp farming has become a hot topic for consumers and restaurants. She just stumbled into at the right time. The Island Institute is working with her on getting a state license to farm kelp and and helping her put together a business plan. Seeding the lines in the fall and harvesting kelp in the spring dovetails perfectly with her down time in the winter, providing her with a secondary sustainable job before lobstering starts again in the summer. A win for Cooper, a win for the ocean, a win for nutrition and for Maine’s economy. What’s not to like?

And to think this has been right under Cooper’s nose her entire life.

Event Date

Address

United States