Camden couple proposes fish ladder plan for Megunticook River, Montgomery Dam rehabilitation

CAMDEN — Tony and Sally Grassi, working with landscape architect Stephen Mohr and engineer Will Gartley, have produced a rehab plan for the Montgomery Dam that incorporates a fish ladder up the Camden Falls. They presented the plan Friday afternoon to a group of residents who care deeply about what the town does at the head of the harbor, where the Megunticoook River flows in the saltwater.

“It is not perfect,” said Tony Grassi, speaking over the phone Friday, Sept. 16. “It is a plan, not the plan. It’s a first step.”

The plan, which the Grassis funded, represents an attempt to move the conversation in Camden about the Montgomery Dam away from polarized disagreements to a solution built on common goals.

“It is something that people can understand,” Grassi said. “As we were out gathering petitions last winter, people kept saying, what would it look like if the dam were removed. Until you can get over that, people won’t understand it and think constructively about priorities. We began to realize when we did this work with Stephen [Mohr & Seredin, landscape architects] it’s about managing the flows and where you are going to steer the water. It has high flows, and low flows and where do you want the water to go, and under what circumstances.”

The Megunticook River Project is an an ambitious effort initiated by the town to increase resilience and restore habitat in the Megunticook River Watershed as a changing climate raises water levels.

A project flashpoint has been the idea of removing the Montgomery Dam, which sits at the outlet of Megunticook River as it empties into the ocean. The dam and the falls are adjacent to the Camden Harbor Park. That park was sculpted on the design of the renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who was hired by Mary Louise Curtis Bok in 1928 to produce a plan for the two acres in front of the library that slope to the water.

“The park is overseen by Trustees of the Camden Public Library,” said Grassi. “Rising sea levels threaten to flood lower sections of the Park that are already inundated at high tides. The solution to protecting the park and its historic resources is inextricably linked to any decision concerning the Montgomery Dam and could also possibly be funded by NOAA.”

Most recently, the Camden Select Board created a volunteer and citizen-lead committee to oversee the project.

Almost simultaneously, the town learned that it is among eight recipients of National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grants for natural infrastructure projects.

Camden’s grant amount, for the “Megunticook River Watershed Fish Passage and Flood Prevention Final Designs and Permitting,” is $1.6 million with a matching fund of $260,000. That matching grant can consist of in-kind volunteer hours, or other related expenses, and not be an additional taxpayer expense, according to a recent Select Board meeting conversation.

Grassi intends to hand over the plan to the Megunticook River Advisory Committee, a natural progression that lays the assessment and decision-making in the hands of the town.

The Sept. 16 presentation of the plan commissioned by the Grassis took place at an afternoon meeting that was to include citizens associated with Save the Dam Falls Committee, as well as the Restore Megunticook group, riverfront landowners, and town employees. Stephen Mohr was to explain how a fish passage would coexist with the Montgomery Dam in place, while preserving the aesthetics where the river cascades over granite ledges, and protect the historic resources of Harbor Park.

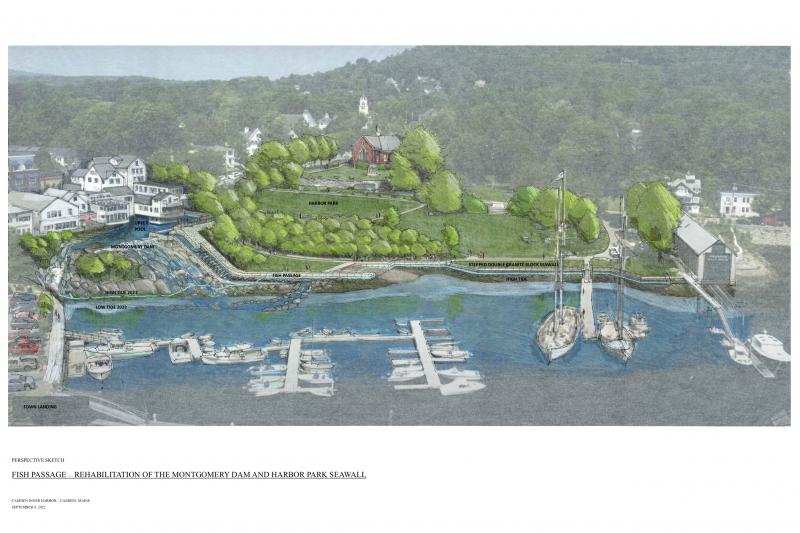

The proposed fish passage would extend approximately 10 feet from, and parallel to, the seawall along the current northern side of the river into the harbor. The lower levels would be underwater except at the lowest tides.

The fish passage would, “allow for a five per cent grade to permit alewives, smelt, salmon, trout and elvers to make their way up the 21-foot-high ledge to the pond above the dam,” according to to the plans. “From there, the fish migration can proceed upriver to Lake Megunticook if the relic dams are removed and fish passages are built around the Seabright, East and West dams.”

To Mohr, the plan represents one solution, a path forward to talk about as a community.

“There is a path forward if we can all just talk about it, and at least we get some clarity,” he said.

Mohr, who has worked on a number of different Camden projects over the last 35 years, (most recently the $5 million reconstruction of the American Boathouse at the head of Camden Harbor), is well connected to the Olmsted legacy. He also has participated in river restoration and dam removals elsewhere in Maine.

He and his firm drew on existing research that is already associated with the Megunticook River Project, as well as a familiarity with the national Historic Registry and federal permitting and funding guidelines.

“The design would preserve a great deal of the Montgomery Dam,” said Grassi. “It would maintain a pond at the old mill site, and it would preserve the river flow south toward the Camden Public Landing.”

It has been more than a century since the river was open to migrating fish. Would the fish still swim upriver if they had the chance?

To Mohr, the genetic imprint fish and eel carry in their cells is powerful.

“We know there are eels and fish there, and the imprinting is there, so I reach the conclusion that part of their mission is knowing the way,” he said.

As for the Montgomery Dam itself, a “significant portion” would remain.

“Only about three vertical feet would be removed from a portion of the dam at the very top,” according to the plan. “The main flow of the river would pass over the central ledges, with the highest flows also spilling out to the south toward the Public Landing. A small stream would be maintained year-round through the fish passage. No equipment or human intervention would be required to maintain this system.”

And, the existing seawall from the Montgomery Dam over to the schooner landing would be raised by four feet.

“It would include a step-down design allowing for human access to the water’s edge at the grounding basin and preserve the existing access at low tide,” the plan said. “Access to the schooners will be through a designed gap in the seawall, with the flexibility to be raised as the sea levels rise. This would provide Harbor Park with protection of four feet from the anticipated sea level rise, which should be sufficient for at least 100 years.”

Funding for executing this plan depends first on an agreement by the town to move forward with it, and then submitting requisite applications to federal agencies and other sources.

Grassi said that without some form of “naturalized fish passage,” Camden would remain ineligible for climate resiliency funding under the federal Infrastructure and Jobs Act of 2021.

The goal is to design and engineer a plan that meets goals and standards set by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the federal agency responsible for reviewing and funding such projects.

“If you are going to get funding for river work from NOAA, which is where the funds flow, then they’ve got approve your fish passage, and say yes it works,” he said. “NOAA will only do it if you meet their criteria.”

Grassi is a firm believer that NOAA maintains high standards and understand all the factors — cultural, environmnental, ecological — that contribute to decisions such as what Camden currently faces.

“They are really good,” he said. “They understand the balances that are required. They are sensitive.”

Grassi declined to discuss how much he has invested in the plan, saying only that it is, “a fair amount.”

But, he added, both Mohr and Will Gartley worked with him on it for reduced rates.

“Stephen and Will Gartley understand the importance of this and both have been at lower than their lower rates,” said Grassi. “They understand this is a service to the town.”

He said he informed Camden Town Manager Audra Caler late last spring about the effort to contract with Mohr and Gartley to produce a plan.

“Sally and I decided to do it, and got Stephen and his wife, Sonja, on board, and then I thought I better let somebody know what I’m doing here,” said Grassi. “I told Audra and a few Select Board members. I wanted them to know, but I also didn’t want to be in the public domain because I wanted to create some answers.”

He hopes that the plan makes way for constructive conversations and forward momentum. He knows that the detailed engineering will change and be tweaked.

“That’s all good,” he said. “I’m hopeful that it is a vehicle to allow people to come together and understand the details on the ground, as well as the tradeoffs that need to be made,” he said. “ And that there is a way to accomplish some of everybody’s objectives.”

He has no desire to be paid for his expenditures.

“My funding covers presenting it, and taking it through this phase, which includes communication, but then it is up to the town of what they want to do with it,” said Grassi. “This can’t be Tony’s plan. It’s our start but ultimately the town has to come together for a solution.”

About the Grassis, Stephen Mohr and Gartley and Dorsky.

Tony Grassi and his wife Sally have lived in Camden since 2003. Grassi devotes his time to addressing environmental issues and is the owner of the Mill at Freedom Falls, in Freedom, Maine. He served as the Chairman of the Board of American Rivers from 1996 to 1999, and was the Global Chairman of The Nature Conservancy, one of the world’s leading environmental organizations, from 2000 to 2003. He also has chaired the Butler Conservation Fund since 2005, and currently serves as the Chairman of the Advisory Committee to the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions at the University of Maine in Orono.

Mohr & Seredin is a Portland-based firm and have practiced in Maine since 1989. The firm has specialized in historic landscapes throughout New England for private individuals and institutions. The partners are both past presidents of the Maine Olmsted Alliance for Parks and Landscapes, which merged with the Maine Historical Society in 2012. Recent Camden projects include the American Boathouse, and the firm continues to work for Historic New England on their properties in Massachusetts and Maine.

Gartley & Dorsky (G&D) is an engineering and surveying firm serving residents, municipalities, institutions, and businesses of Maine from offices in Camden and Damariscotta. The company, formed in 2003 by Will Gartley and James Dorsky, provides civil, structural, and mechanical engineering, surveying, permitting, and soils and wetland science services for large and small projects across the state. From the small (residential additions and septic designs) to the large (ALTA surveys and full-service site planning on subdivisions and commercial developments), it strives to provide each client with great service and cost-effective solutions. G&D has worked on multiple fish passage projects in recent years, and has engineers experienced in historic rehabilitation and preservation.

Reach Editorial Director Lynda Clancy at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com; 207-706-6657