As families struggle to afford phone calls from jail, Maine counties rake in millions

She set dinner on the table before sharing the bad news with her 10-year-old son Wyatt.

On and off throughout Wyatt’s life, his father has been incarcerated at the Kennebec County Correctional Facility in Augusta. Most weeks his mom, Courtney Allen, scraped together $50 to pay for a few 15-minute phone calls from the jail. That week she didn’t have the money.

“My son is very, very quiet and wise beyond his years. He’s seen a lot of things,” Allen said. “He kind of looked at me and said, ‘Mom, why are the phone calls so expensive? Why am I being punished for my dad’s mistakes? I just want to talk to my dad.’ “

For three years, Allen made it her mission to make jail calls cheaper. She found an ally in state Rep. MaryAnne Kinney (R-Knox), who sponsored a bill this year to cap the cost at 11 cents a minute and ban state, county or municipal governments from making money off services provided to incarcerated people.

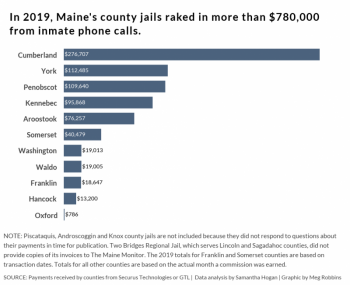

But private phone contracts are a multi-million dollar industry in Maine. Companies have paid county governments at least $3.3 million over five years in revenue-sharing agreements for exclusive telephone contracts at the jails, which inmates and their families must pay into to communicate, an investigation by The Maine Monitor found. The Department of Corrections has also cashed in on lucrative phone contracts for more than a decade.

The county jails provide phone services through two of the largest prison telecommunication companies in the country. Thirteen counties use Securus Technologies while Two Bridges Regional Jail and Somerset County use GTL, or Global Tel Link. The six correctional facilities that make up the state prison system use Legacy Inmate Communications. Their contracts set the price of calls, text messages, tablet usage, video visits and the amount the jail or prison will earn from getting inmates to use each product.

The fees and price-per-minute of phone calls vary widely, despite many facilities using the same vendor. There is no easy way to calculate how much a call will cost. York County Sheriff William King held up a table of the prices and fees charged at each jail he compiled for lawmakers, who were considering Kinney’s bill: “I’m finding it very, very confusing,” he said.

The Federal Communications Commission, or FCC, capped the price of interstate phone calls at jails and prisons because of the limited options incarcerated people have to select a provider. But courts have ruled the FCC does not have authority to set prices locally, and states must regulate the cost of in-state phone calls from jails and prisons.

Maine has done the opposite. The Maine Monitor reviewed phone contracts for county and state correctional facilities, and monthly payments to 13 counties in the past five years. The records showed multiple counties enrolled in expensive phone plans, and in return earned lucrative signing bonuses and monthly commissions off the money families paid into the systems.

Jails are controlled locally by the county sheriff and are designed to house people prior to trial or serving short sentences. The Maine Department of Corrections operates the state’s five adult correctional facilities and a juvenile detention center in South Portland.

State law requires that money earned from telephone calls by jails or prisons be spent to better the lives of inmates, but there is little transparency about how the funds are spent — or, in some counties, if the money is spent at all.

The Maine Sheriffs’ Association, which represents the county jail system, said it unanimously opposes Kinney’s proposed legislation. The cap would prevent competitive bids for phone services, and a provision that would allow two free phone calls a week per person would have to be absorbed by taxpayers, according to the association.

Family members of people being held at Maine jails say the state and local governments need to stop generating revenue from their phone calls, because it amounts to an unfair tax.

“Families are paying for these phone calls, not people who are incarcerated. People on the outside who are everyday, average taxpayers, who have done nothing wrong, are the ones holding this brunt just because we love someone who’s incarcerated,” Allen said. “It’s a completely unfair double tax.”

‘These children are our future’

Kinney admits she knew little about the cost of phone calls at the jails before sponsoring her bill this year. She’s never had a family member incarcerated, but stories about how the expense was affecting kids hit home.

One woman said she worries about whether she can find her pocketbook fast enough to punch in a credit card number — often running over her card’s limit — so that her nephew’s kids can speak to their father.

Another woman said a friend sometimes goes without food or fuel to afford speaking to an incarcerated son.

A man who spent time in jail said he watched people barter for 10-minute phone calls with the promise to repay the time three-fold — 30 minutes — when they had money added to their account — just to be able to speak to family.

“I suspect to a point the county jails will be a little opposed because they’ll lose funding,” Kinney said. “But we should find other ways to fund our jails than put additional costs on kids who want to talk to mommy and daddy.”

In the past five years, at least 3,403 children in Maine were separated from a parent serving time in prison, an analysis of parental incarceration shows. This does not include Maine county jails or federal correctional facilities.

“We know it’s an undercount,” said Erica King, a senior policy associate with the Cutler Institute at the University of Southern Maine and a lead author of the report.

Research has shown parental incarceration is an adverse childhood experience, or ACE, that can trigger family instability, and increase the risk of homelessness, depression, anxiety, economic instability, low educational attainment and involvement in the juvenile justice system.

Erica King’s analysis found children in Maine are often not the victims of the crime their parents were incarcerated for, and very few parents were ordered by the courts to have no contact with their children. For most parents, there is no legal reason to prohibit contact, she concluded.

The report recommended the state facilitate technology for parents who are incarcerated to be more frequently present in their childrens’ lives, such as remote participation in teacher conferences, sporting events and performances.

“The research and data is very clear about what the arch of healthy child development is, and it includes secure and healthy attachment with parents and caregivers,” Erica King said. “Rather than thinking about it through the lens of punishing the parent, looking at it through a child development lens. These children are our future so we need to make policies that are going to equitably advance their development if we’re ever going to end the cycle.”

The money earned off phone calls is supposed to be reinvested into the jail or prison’s population, but Rep. Victoria Morales (D-South Portland) said using them as a funding mechanism was wrong. Having connections with family is important to re-entry and reducing the chance of repeat offenses, she said.

It was “shocking” that Maine counties earned over $3 million from jail phone calls, she said. The Department of Corrections said it also had a balance of $1.2 million of unspent revenue meant to benefit inmates.

“That’s a lot of money that could support folks, but it’s also a lot of money that we’re taking from folks that I don’t think we should,” Morales said.

The cost of connection

Cumberland County has reaped the most money of the 13 county jails contracted with Securus Technologies for phone services. In the past five years, the company paid at least $1.2 million to Cumberland County for telephone costs incurred by jailed people and their families, a review of payments by The Maine Monitor shows.

Securus Technologies pays an average of $21,600 a month to Cumberland County, payment records show.

Jacorey Monterio has been in and out of county jail and state prison for the past decade. His latest stint at Cumberland County Jail lasted almost two years because of the pandemic. In the Maine prison system, where calls cost $0.09 a minute, it’s difficult to rack up a large phone bill, he said. But it takes only a few telephone calls at a county jail to do the same.

Monterio had a job at the Cumberland County Jail and earned $12 a week. It was barely enough to make a few phone calls.

“For the most part here it’s just really expensive. If I didn’t have people taking care of me I wouldn’t be able to talk to my immediate family as often, because they don’t have the financial capabilities to really pay. You know, $20 a week you can probably call someone five or six times for 15 minutes apiece,” Monterio said.

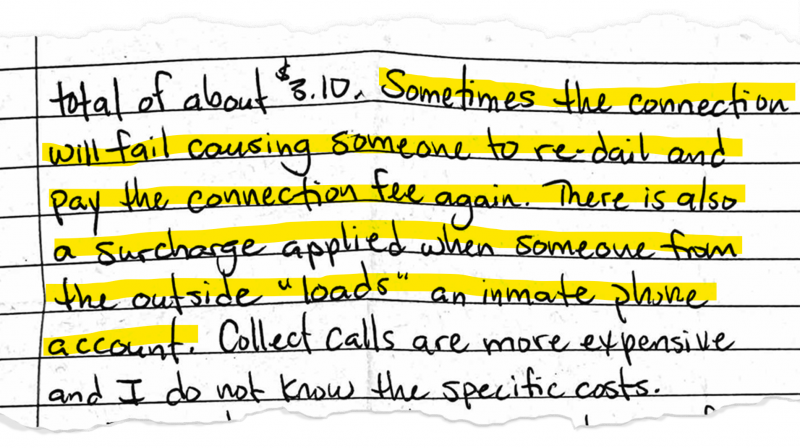

An extended family member adds money into an account for him to be able to stay in contact. But there are surcharges every time money is deposited. To make the maximum deposit of $300 online there is a $11.95 fee, he wrote in a letter and confirmed by The Maine Monitor. The fees lower incrementally but people are charged $4.95 to add less than $20 to a person’s account.

The fees are even higher to send money over the phone, and the kiosk in the jail’s lobby charges $3 for deposits, according to a fee chart provided by the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office. The only method to add money without a fee is through a money order.

The money doesn’t go far. At the time, Monterio was working with a recovery coach, Sarah Siegel, on a substance use disorder. The first minute of their phone call cost him more than a dollar to connect and 14 cents a minute, he said, before the call automatically cuts off at 15 minutes. Their session lasts an hour, which means Monterio calls four times and pays a connection fee on each call.

Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce said the jail recently eliminated its connection fee and changed the cost of in-state calls to 26 cents a minute.

Siegel said the time restraints and costs are stressful for her, too. She uses an interviewing technique that helps get people to the action phase of their recovery. It requires a lot of listening. There have been times when Monterio is beginning to open up and a warning interrupts their conversation to announce there’s a minute left on the call.

“The amount that he actually wants to get better is really astounding and beautiful. And so it’s equally as frustrating when there’s these just totally unnecessary hurdles,” Siegel said.

Even for families that have money, the cost to stay in contact adds up fast.

It cost $4,000 for Uria Pelletier to speak to his brother-in-law while he was being held at the Cumberland County Jail for eight months, he said. Pelletier owns multiple businesses in Waterville and is a member of the city’s Planning Board. He can afford the calls, but many people he has met don’t have the money. The counties’ phone contracts punish families financially, he said.

“Everything is expensive when it comes to jail. I just don’t think you should incentivize prisons and caging humans as a means of income — for profit — especially, when the facilities themselves are paid for by taxpayers,” Pelletier said.

Counties cash in on communication

County sheriffs and the Department of Corrections have little motivation to end their contracts with private telecommunication companies despite the costs to families.

Instead of calls getting cheaper, companies have added services and technology that have further driven up the costs for people in jail. One service Securus Technologies provides to county jails is video visitation terminals. A video visit costs $20 for 20 minutes or $40 for 40 minutes plus fees.

The counties with video visits agree to push jail residents to make video calls, including a contract stipulation that says jails, “will endeavor to reach at least one remote paid Video Visitation session per inmate per month,” according to contracts reviewed by The Maine Monitor. This ensures the jails “maximize full utilization” of the video visit platforms so Securus Technologies can recover its upfront costs of installing the equipment.

But the platform offered by Securus Technologies has low quality video and high prices, The Marshall Project reported in 2019. The Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that researches mass incarceration, questioned in a 2015 report why expensive video visits were being offered to historically poor families, and potentially replacing in-person visiting hours at jails and prisons.

Securus Technologies said it spent around $500,000 on its hardware, infrastructure and network in Maine in the past three years, according to information provided to the sheriffs’ association and lawmakers. The company did not return a request for comment.

The jails and prisons receive direct payments for offering telephones and video visits to people. The money earned is required to be deposited in an “Inmate Benefit Fund” and spent to better inmates’ lives, according to state detention standards. But some county jails and state prisons have substantial balances of unspent funds. Take York County for example.

Over $558,000 was paid to York County in the past five years, and more than $465,000 was unspent as of May.

York County receives 95 percent of the revenue from collect calls and debit calls completed from the jail, according to an agreement with Securus Technologies.

County Manager Gregory Zinser said York County spends the money it earns from phone calls on cable and newspaper subscriptions, chaplain services, commissary bags around Christmas and during the pandemic, seasonally appropriate clothing for people to wear when they are released, haircut tools, law library access, and other educational supplies and programs.

“The commissions (from Securus Technologies) are deposited into the Inmate Benefit Fund and must be used for the benefit of the inmates. I don’t want that getting lost in this whole equation,” Zinser wrote. “The commissions received cannot be used as any type of revenue offset.”

Zinser stopped responding to questions from The Maine Monitor about why York County had a balance of $465,664 in its benefit account or why the county had not spent more money on the needs of inmates.

A costly cycle

Families asked the Maine Public Utilities Commission, or PUC, back in 2007 to investigate whether the telephone rates offered at the state prisons by the Department of Corrections were reasonable. At the time, the prisons were charging 30 cents a minute, while the average Maine resident was paying 3 cents.

The PUC tried to regulate the cost of phone calls from the state prison, but the Maine Supreme Court ruled that the PUC could not regulate a state agency like a public utility. The court decided the Department of Corrections had exclusive authority to set telephone rates at the state prisons, said PUC spokeswoman Susan Faloon.

T-Netix, the phone provider for Maine State Prison at the time, wrote in response to the families’ complaint, “if a consumer feels the rate is too high they may decline the call because there is no obligation to accept and no charges will be incurred.” T-Netix and Evercom Systems merged in 2004 and launched Securus Technologies.

Legacy Inmate Communications now provides phone services at the five adult prisons and Long Creek Youth Development Center for $0.09 a minute, which the state earns $0.05 back. There is a balance of $1.2 million in the inmate benefit accounts at five of the state’s prisons, said Commissioner of Corrections Randall Liberty.

The department would not say why each prison had a significant balance or why the money had not been spent on the betterment of inmates’ lives.

The Department of Corrections refused to make Liberty available to The Maine Monitor for an interview. In response to written questions, an agency spokeswoman, Anna Black, said the cost of phone calls were aligned with industry standards and not set by the department. Factors, including the size of the prisoner population, affected the balance of the prison’s inmate benefit fund, she said.

The Department of Corrections does not see its above-market rates for phone calls as a “tax,” Black said.

The agency spent $908,000 it earned from its phone contract on “quality of life” expenses last year, including cable, gym and sporting equipment, haircuts and food items for the residents of state prisons, Liberty told lawmakers.

Half of one percent of the money spent went to phone calls for inmates who were unable to afford them, department records show. To qualify for free calls, the person must have no money in their facility account and no personal savings or investments, according to the state’s detention standards.

Rep. Danny Costain (R-Plymouth) said the state budget, not families, should fund expenses currently covered by earnings from the phone systems.

“If you feel those things are that important, then we need to look elsewhere for it and not put it on the taxpayers that are already paying taxes to run the facility as it is,” Costain said.

Lawmakers tabled Kinney’s bill until at least 2022 so the sheriffs’ association, Department of Corrections, families and lawmakers can make amendments.

For a person in one of Maine’s county jails or state prisons there is no easy way to call home. Fees, surcharges and taxes all add up before their first word and the clock pushes the cost higher. The price is stressful to them and their families.

To make sure her sons stayed connected with their father, Courtney Allen carved out time for a 15-minute phone call multiple times a week.

Her son Wyatt is now 13 and his dad is out of jail. Still, Allen remembers the nights when he couldn’t get to a phone until 8 or 9:30 p.m. Wyatt and his brother were tired and should have been in bed, but they wanted to talk to their dad.

“But when we finally did get on the phone and the kids had the time to talk to their dad, they’d talk about soccer or what they’re learning at school,” Allen said. “And it’d feel really normal for those 15 minutes.”

Maine Monitor researcher Caleb Horton contributed to this report.