Belfast man pioneered physical education, influenced basketball’s creation and field hockey’s U.S. introduction

BELFAST — Whenever one generation studies its predecessors, it is evident how influential some movers and shakers were during their lifetime.

Some innovations can be spotted near immediately; say, the invention of the electricity. The profound impact of others, however, is not truly grasped until future generations study history.

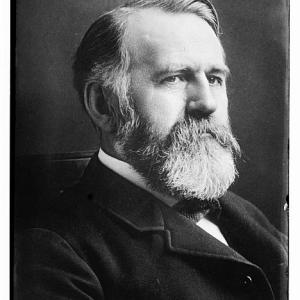

The latter is true for one of Belfast’s most important citizens, a man by the name of Dudley Allen Sargent, who pioneered the field of physical fitness, physical training and physical education.

Sargent’s legacy, and how it has affected our culture, does not end with his influence on physical fitness.

The Belfast native played a key role in the game of basketball’s creation, provided an opportunity for basketball’s popularization among Blacks, and opened the door to the popularization of field hockey in the United States.

Sargent, additionally, developed a strength test still used in the present day by basketball and football players as they shift from being a collegiate athlete to professional one.

Early Life and Physical Education

Sargent, a Belfast native born in 1849, lived in Belfast until age seven. That year, following the death of his father, Benjamin was sent to live with relatives in Hingham, Massachusetts.

Three years later, Sargent returned to Waldo County to live with his uncle, widowed mother, and younger sister.

Academically, Sargent was placed among students two or three years younger than himself. At the Select School, which offered no gym, Sargent innovated by erecting a horizontal bar with friends.

“This horizontal bar was unique, however; for while all the apparatus at High School was made of wood, ours was iron,” Sargent wrote in his autobiography. “Its chief advantage was that it was small enough to grasp comfortably, and at the same time strong enough to support the weight of several bodies at one time.”

Wood bars at the time, Sargent wrote, were made too large for comfortable grasps.

Sargent gained his interest, according to academics Jason P. Shurley, Jan Todd and Terry Todd in their 2019 book “Strength Coaching in America: A History of the Innovation That Transformed Sports,” in physical training as a young 14-year-old when he saw an image of Professor Henry Thomas Harrison swinging heavy Indian clubs in a text called, “The Family Gymnasium.”

“The adolescent Sargent ‘regarded this man Harrison’s physique with envy’ and crafted his own Indian clubs in an attempt to build a physique similar to the Englishman’s,” wrote Shurley and the Todds.

But, the group learned the iron bar was not suitable for outdoor winter use.

“In one winter contest, the frost caused the iron to stick to the skin, and all the participants lost patches of skin from the palms of the hands,” wrote Brenda B. Boynton, in a master’s degree thesis for Boston University, in 1942.

By age 13, Sargent had dropped out of school from a lack of interest in academics amid the Civil War. He, instead, accepted employment with his uncle for $1.50 per day on a government battery being constructed in East Belfast.

A year later, the batteries were completed and Sargent returned to school with a desire to seriously pursue an education.

During the winter of 1864, Sargent entered high school. Many of his friends attended a boarding school in Topsham where they developed an interest in gymnastic exhibitions held at nearby Bowdoin College in Brunswick.

In a return to Belfast, the Topsham students formed a gymnastic club that Sargent joined.

His time as a member, however, proved short as he was expelled after breaking a piece of an apparatus with a friend.

Now keen on gymnastics, Sargent converted his uncle’s barn into a temporary gymnasium and specialized in working with the horizontal bar.

Sargent rapidly developed a reputation among Belfast’s residents as a gymnast and showcased his talents to the public in February 1867.

Shortly thereafter, Sargent formed his own company, Sargent’s Combination, that traveled to nearby towns.

“Many Belfast parents refused to allow their offsprings to associate with a boy who indulged in what they called ‘monkey shines,’” wrote Boynton.

By this time, Sargent began training to become a professional gymnast. He and a friend, following a series of performances, were invited to perform as extras with a circus performing in Belfast. The duo would go on to perform with a traveling variety show.

Sargent, upon his return from the circus to Belfast, was treated as an outcast for his participation in the circus.

His desire for education had once again subsided, while his fervor for gymnastics increased.

Sargent bought a new apparatus and began a systematic training for a professional career, while looking to involve other boys in his work.

“He started by encouraging the boys to develop strength by means of pulley-weights, and skill by means of adjusting the apparatus a few inches from the floor,” wrote Boynton.

A friend from his days in the circus offered Sargent the opportunity to travel to a large city for a month-long engagement performing a bar and trapeze act. Traveling under assumed names, one month turned into four.

Sargent returned, once again, to Belfast, in fall 1868, and was now, again, yearning for a proper education and profession.

Law, ministry and medicine intrigued Sargent as he pondered professional endeavors.

Ultimately, he settled instead on a career in gymnastics, with a concentration in physical education thanks to a life-altering event at a Belfast church on a Sunday morning.

Sitting in front of an open window, Sargent recalled in his autobiography, he sat listening to the reverend having only slept for a few hours before church because he had worked late for his uncle the day prior.

“Softly and quietly I slipped off into a gentle doze,” Sargent penned. “But as my head fell back, my eyes opened for an instant, and I looked up at one of the supporting rods. My reaction was instantaneous. I jumped forward and upward to grasp the rod. My awakening was rude and complete. I tried to recover myself, and in the effort nearly fell backward through the window. It was, of course, the automatic action of the muscles, which I had trained to protect myself in mid-air gymnastics, that made me jump for the bar on this most inopportune occasion.”

By June, a friend at Bowdoin traveled to Belfast with news of a prospective job opening to Sargent — Bowdoin College had a vacancy in its gymnasium.

Sargant, keen on securing the position, secured letters of recommendation from an abundance of individuals, though there was one particular recommendation that would, ultimately, help Sargent the most.

Reverend Worcester Parker, the Congregational minister in Belfast, was the father-in-law to the daughter of Bowdoin College’s president, Samuel Harris.

When Harris visited Parker in July 1869, Sargent was invited to call and meet with Harris.

Sargent, following an interview with Parker, was named the Director of Gymnastics at the Brunswick institution. His contract began a couple months later, in September, for a salary of $5 per week.

The Bowdoin gymnasium was in dire need of work, however.

“The gymnasium [...] was a low-studded, ramshackle building with floor space quite inadequate for anything but the most constrained exercise,” wrote Boynton. “All of the equipment in the gymnasium was of the heavyweight class and was far too strenuous for the untrained main.”

Sargent was tasked with reducing the weight of the Indian clubs by turning them down, Boynton wrote, and to reduce the weight of the weight pulleys by the use of a detachable pulley and a double length of rope, a mechanism displayed at the school for years after Sargent’s departure.

At Bowdoin, students were predominantly avoiding the gymnasium, Shurley and the Todds chronicled, as the minimal weights in the facility were far too heavy to lift, resulting in students lacking training experience.

“In order to work around this impediment, Sargent invested in light dumbbells, Indian clubs, and adjustable pulley machines that would accommodate varying levels of strength and training experience among the student body,” Shurley and the Todds wrote. “With the new apparatus, students saw significant results in a relatively short time.”

In his position at Bowdoin, he was tasked, according to Boynton, with staging a gymnastics exhibition at the end of his inaugural semester. His students showcased exercises in light and heavy gymnastics, work on the bars, rings, and trapeze, a dumbbell drill, and an Indian club drill.

Sargent was rewarded by prestige with the institution’s president and faculty for the successful exhibition, in addition to a salary rise from five dollars per week to $500 per year.

As he accelerated in success at the gymnasium, his yearning for education, once again, returned. He received tutoring from several individuals and enrolled in a college preparatory class at Brunswick High School before enrolling as a student, in 1872, at the same institution that employed him.

By 1872, Bowdoin mandated males participate in both gymnasium work and military drills five days per week. A year later, the administration bowed to criticism and amended the ruling to allow students to choose between the two.

To comply with this new requirement, Sargent knew he needed to obtain a new preparatory apparatus for those unfamiliar with gymnastics. To do so, Sargent rebuilt some of his old apparatus from his Belfast days, according to Boynton.

Nearly everyone elected to participate in Sargent’s gymnasium program by 1874, which would be Sargent’s sixth and final year in Brunswick.

It had been decided, around the end of 1872 and beginning of 1873, the Bowdoin gymnasium would be closed for the winter months as the building was cold and dreary.

With the Bowdoin gymnasium closed for three months in the winter, Sargent would spend the time working at the Yale University gymnasium in New Haven, Connecticut until his return a few months later to Bowdoin.

“Like his preparation at Belfast, his college work had been interrupted by gymnastics, too,” Boynton wrote. “Due to his two leaves of absence [to work] at Yale, and the necessity of spending from two to four hours in the gymnasium every day, Sargent found it a real task to keep up with his class.”

Despite the challenges, Sargent earned his bachelor's degree from Bowdoin in 1875.

In fact, Sargent also won the English department’s competition for seniors, with a grand prize of $60, for his oration entitled “Does Civilization Endanger Character?”.

At the outset of summer, Sargent parted ways with Bowdoin after the institution rejected an offer of his to, essentially, renegotiate his contract.

“His experience at Bowdoin caused Sargent to shift his view of training, from emphasizing strength to democratizing exercise and focusing on balanced physical development rather than maximizing ability at one skill,” penned Shurley and the Todds.

Sargent returned to Belfast for the summer before enrolling at Yale to study medicine in September 1875.

Though participation in gymnasium work was optional to Yale students when Sargent began there, in 1873, participation sharply rose by the spring term of 1874 that Sargent had to add an additional instructional period.

Impressed by his work, Sargent’s Yale colleagues concocted a plan for him to reach the non-athletic men, who needed exercise instruction the most.

“Up to this time, every freshman had been required to take an hour of Greek on Saturday mornings, but this year, the faculty allowed each freshman to choose between the Saturday morning Greek, and two thirty-minute periods of gymnasium work,” Boynton wrote. “Since the gymnasium work saved an hour of preparation for the Greek class, all but two or three men elected gymnasium work.”

The gymnasium work was divided according to scholastic standing, Boynton noted, and the 30 minute courses would consist of dumbbell drills for 15 minutes and Indian club work for 15 minutes.

“Since it was necessary for the men to work in their shirt sleeves, because of the lack of facilities for dressing rooms and showers, Sargent’s job was to make them work, but to keep them just short of the perspiring stage,” wrote Boynton.

With Sargent now a member of Yale’s medicine program, he became too busy with his education to allocate as much time to the gymnasium.

“He continued his work as a sort of general director, teaching volunteers one hour every day, and conducting freshmen classes twice a week,” Boynton noted.

Sargent earned his degree in medicine in January 1878 and continued working at the school’s gymnasium until April of that year.

During the first four months of 1878, Sargent devoted his time to devising a system of physical education adaptable for American schools, colleges and universities.

By that point, Sargent’s relationship with Yale had begun to sour.

“President [Noah] Porter, of Yale, discouraged Sargent in every way from taking up physical education as a profession,” Boynton wrote. “He not only could offer no hope of an opening at Yale, but he thought the work was unworthy of a college-bred man.”

Sargent began writing to roughly a dozen college presidents across the country, Boynton detailed, to propose a department of physical education at their institutions.

“For the most part, the replies which he received were polite and courteous, but he found, in 1878, that education was not ready to consider mind and body together.

After his time at year, Sargent briefly operated his own gymnasium in New York before shuttering the facility and being lured back into academia.

In August 1879, President Charles W. Eliot, of Harvard University, wrote a letter to Sargent offering Sargent the opportunity to join the Cambridge, Massachusetts institution.

Sargent accepted the appointment, with a title of Director of the Gymnasium and Assistant Professor of Physical Training, and yearly salary of $2,000 “plus the rental of the dressing-room lockers, the use of two hours daily in the forenoon for private practice in Boston,” according to Boynton.

Part of the reason Sargent is recognized by historians as a tremendously influential individual is due to his employment at Harvard.

“The brand association from being the Director of Physical Education at that prestigious institution bestowed more seriousness on his ideas than if he had been employed elsewhere,” explained Shurley, in an email.

His appointment at Harvard, however, was opposed by many at the institution.

“Many of the overseers, feeling that physical training was not a profession worthy of an educated man, opposed Sargent’s appointment as ‘Assistant Professor,’” wrote Boynton. “When his five-year appointment was terminated, Sargent’s title became simply, ‘Director of the Hemenway Gymnasium.’ The faculty objected to the investment of over one-hundred thousand dollars in anything as unnecessary as a gymnasium.”

The Hemenway Gymnasium was completed at the end of 1879, with Sargent providing input into its design, and opened for use by students at the beginning of 1880.

“Sargent used Harvard's significant financial resources to design and build advanced versions of the machines he had first used for training back at Bowdoin,” said academic Carolyn de la Peña (now Carolyn Thomas) in her book “The Body Electric: How Strange Machines Built the Modern American.”

At Harvard University, Sargent sought to study, in depth, university students in an effort to compose what he hoped would constitute the typical — and, perhaps, perfect — American.

Individuals — initially just men, but later women — were asked to fill out a card about their body and background.

“Each measurement card notes detailed measurements of the subject's body and lists some genealogical and family health information as well,” a description of the cards, stored today in the Harvard University archives, denotes. “This information often includes the subject's birth date and place, subject's father's occupation, and both the nationalities and the causes of death of the subject's parents.”

Each aspect of their body would be examined with one’s heart, lungs, skin condition, spine and muscle carefully examined by Sargent.

“From this knowledge of the individual, a system of individual exercise was prescribed, including the amount of work, and the adjustment of the apparatus,” Boynton wrote of Sargent’s work, which also instructed students on their diet, sleep and styles of clothing.

Sargent was unable to convince Harvard to mandate physical education classes for all students, de la Peña noted.

The field of physical education in the early to mid-twentieth century was engaged in a professional philosophical struggle, according to Shurley, over if the field should focus on the education of the physical — meaning, developing physical skills — or education through the physical — meaning, using games and training to develop character skills such as persistence, teamwork, hard work and toughness.

“Sargent was influential upon the former school — education of — in that his programs were largely training-based (rather than using sports and games) and focused on helping student achieve an ideal, balanced form,” Shurley explained.

Despite classes not being mandated at Harvard, each student was required to meet Sargent for a physical examination and be shown an exercise regimen, de la Peña wrote.

“Even if each freshman entered the Hemenway only once, at least 250 [students] a year received a personal introduction to Sargent’s machines,” de la Peña noted.

Photos of each individual were taken during the examinations by Sargent, who later recruited protegees of his at other coeducational institutions (including Yale, Swarthmore College and Oberlin College) and women’s colleges (including Vassar College, Smith College, Wellesley College, Bryn Mawr College and Mount Holyoke College) to also have students participate in the naked evaluations.

“The photos feature each man from behind, head-on, and in profile. In profile, the subject’s hand holds a vertical measuring stick outstretched,” wrote Clara J. Bates in a 2018 piece for The Harvard Crimson. “The three images are arranged side-by-side on a thick white note card, each of which is tucked into an envelope. Hundreds of envelopes line each box. The men gaze into the camera seriously, chins tilted up—for the most part, seemingly unconcerned with the prospect of a 19-year-old girl peering back at them 120 years later.”

The photos were a necessary part of his work as a physical education instructor.

“Sargent believed precision was possible only when measuring students nude; the photographs likely served as an element of this extensive data collection, though he rarely referenced the pictures in his own writing,” Bates detailed.

After six months of the initial examination, another examination would be conducted to determine what, if any, progress had been achieved.

“After working for ten years among students and athletes, he came to the conclusion that body size and measurements alone did not furnish sufficient data upon which to pass a judgement of man’s physical power or working capacity,” wrote Boynton.

One Harvard alumnus, according to de la Peña, recalled in 1919 he and he friends exercised near daily under the guidance of Sargent.

“They recalled that Sargent had measured their strength, ‘showed us where we were weak and assigned us to practice on his development apparatus,’” de la Peña detailed.

Eliot, the Harvard president, gave public endorsement to Sargent’s system, according to de la Peña, “citing its ‘greater service to weak, undeveloped persons than to those already strong’ and its training of athletes through ‘moderate and symmetrical muscular development.’”

Sargent was most interested in examining body measurements rather than observing bodies at work, de la Peña noted.

“He viewed machine-derived measurements as accurate gauges of strengths and weaknesses,” de la Peña wrote.

Shurley, in an email, shared a similar statement noting the quote-unquote perfect physical form, in Sargent’s eyes, occurred when “the muscles were symmetrical and balanced with other groups, but the physique was not overdeveloped to the extent that the overdeveloped muscles would take away from the nervous or other organ systems (a common misunderstanding of physiology at the time).”

For students to achieve the balanced form, Shurley explained that Sargent developed a series of exercise machines to train specific muscle groups.

While at Harvard, Sargent frequently penned pieces for newspapers and journals, providing input on a range of topics from things he opposed, such as the abuse of military drills in public schools and excesses in athletics, to the things he wished to see adopted across the nation, such as physical education and the end of long skirts being worn by females (he suggested women wear divided skirts for athletics).

The Society for Collegiate Instruction of Women, in 1881, asked Sargent to organize a physical education training department for its students in Massachusetts at the Harvard Annex (which later became better known as Radcliffe College, the all-women’s higher educational branch of Harvard.)

Sargent obliged, and was, eventually, able to expand into larger buildings throughout the years to meet demand.

Sargent, despite his own wishes, erected a new building in 1904 to appease the graduates and teachers of the Sargent School, who felt the old building was not worthy of being upgraded, according to Boynton.

“Although the new building was but one gymnasium in depth, it had classrooms on the second floor and a second gymnasium on the top floor,” Boynton detailed. “In 1914, a new gymnasium was added with two new classrooms overhead, and in 1930, a fifteen-thousand dollar laboratory was added.”

Sargent operated his institution from the start, in 1881, by a motto Sargent lived by, according to Boynton: “Influenced by all, biased toward none. Safeguard for ever being tempted to follow any new-fangled fad blindly, or to refuse to accept something new merely because it is new.”

Sargent was inspired by a variety of lifestyles exhibited by European nations, Boynton noted: the strength-giving gymnastics of the Germans, the active qualities of the English sports, the grace and suppleness of the French, and the poise and precision of the Swedish.

In the late 1880s, with many individuals being placed in charge of gymnasiums despite minimal or no formal training, Sargent sought to launch his own physical education school to provide instruction to the nation’s physical education teachers.

He proposed the summer program to Harvard University, which already had a variety of programs for professionals in the summer.

The university, however, rejected the proposal to add the course to its slate, though Harvard did allow Sargent to use their facility for the course.

Sargent, in 1887, distributed advertisements of his summer course program for physical education teachers. The course was slated to be five weeks, focused on the theories and practice of physical education, for $50.

Fifty-seven students, including 39 women and 18 men, enrolled in the inaugural July session.

This program, Shurley detailed in an email, is also chief among reasons for why Sargent became such an influential educator.

“There were few routes to a credential in physical education at the time, so many of those who were interested in joining the field trained under Sargent,” said Shurley. “They then brought his ideas to Johns Hopkins, Yale, Penn, the University of Iowa, and other institutions across the country.”

Upon learning of the program’s success, Harvard opted to add the program to the slate of studies offered by the Harvard Summer School.

Sargent recruited the finest teachers for his school, Boynton noted, with teachers divided into a trio of groups: instructors for theory courses, instructors for practice courses and student assistants working in exchange for tuition waivers.

“To his credit, Sargent sought to make his physical education summer program more scientific than simply teaching games and exercises,” Shurley noted.

The curriculum of Sargent’s summer program is, in part, what made the program shine as the pathway to being an educated member of the physical education field.

“[T]he curriculum included separate courses in anthropometry, applied anatomy, exercise physiology, first aid, ‘physical diagnosis’, and ‘medical gymnastics’ (akin in concept to rehab exercises),” said Shurley.

Yearly attendance in the program was less than 90 for the first decade, according to Boynton, while the average number of instructors held at 27.

Sargent introduced a graded program, in 1899, that required students to spend two summers in residence.

The graded program was extended to four summers, in 1902, at the behest of Eliot, Harvard’s president.

“This was done with apprehension, for the additional expense of the added courses, and the extended time necessary for the degree, carried no assurance that students would be willing to sacrifice the extra time and money,” Boynton wrote. “These fears were soon proved groundless, for the average attendance of the first ten years of this four-year program was one-hundred and fifty, surpassing by fifty students the average attendance of the first ten years of the school.”

The summer program was so successful, according to Boynton, that it drew students to the Massachusetts college from as far as California to receive the proper education and coveted Harvard Certificate.

“It’s annual registration was not phenomenal in terms of a summer’s registration in any physical education school today, but the geographical distribution of that registration, and the positions held by its student body was unusual by any standard,” Boynton wrote in 1942.

The summer program also contributed to Sargent pioneering the field of physical education.

“The Harvard Summer School of Physical Education thoroughly established physical education on an educational basis, not only in most colleges, but also through state legislation providing for physical education in public school systems,” detailed Boynton.

The program, by Sargent’s account, was a roaring success for the field of physical education.

“l feel that this course did more to further the cause of physical education and to make a homogeneous group of people familiar with its purposes and ideals than any other single influence,” he wrote in his autobiography.

The summer school was influential in the careers of several prominent historical figures such as Booker T. Washington and Teddy Roosevelt.

Within the field of physical fitness, Sargent counted Charles H. (CH) McCloy and R. Tait McKenzie among his alumni.

McCloy, Shurley explained, became one of the most vocal advocates on the importance of training students to improve their physical abilities through the “education of” philosophy, and, through his work at the University of Iowa, was “extraordinarily influential” in the field himself.

McKenzie, Shurley detailed, has been credited as the first physical therapy professor in the United States while at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Sargent School would later add a summer camp option, in the early 1900s, for its female proteges in Hancock, New Hampshire.

The final cohort of male students at the Sargent School of Physical Education was the class of 1913.

“The School never had more than a few men in scattered classes,” Boynton detailed. “Since there were no facilities for large numbers of young men, it was decided to drop them entirely.”

By this time, Sargent’s wife and son became heavily involved in the Sargent School, a fact that would later prove important to the future of the institution.

Sargent’s son, Ledyard, was promoted to Assistant to the President at the school, in 1914, after serving as an instructor in physics and chemistry. Six years later, Ledyard, again, was promoted to Vice President and Director. Sargent’s wife, Ella, became the Dean of Girls in 1922.

Two years later, in 1924, the elder Sargent admitted to failing health conditions. He passed at the Sargent House in Peterboro, New Hampshire in July of that year, leaving the institution he founded in the hands of his wife and son.

The school was directed by Ledyard and Ella during its most crowded years, noted Boynton.

“During these years enrollment increased and many changes occurred in the physical education field,” detailed Boynton. “Competition was keen. Universities, colleges and junior colleges began to offer courses in physical education, leading to degrees.”

Degrees being offered by competitors proved to be a struggle for the Sargents, determined to keep the legacy of their beloved alive.

“Although the Sargents recognized the superiority of their training over the almost elementary courses in physical education given in some of the small colleges, the status of the Sargent graduate was not equal to that of the graduated with a degree after her name,” Boynton detailed.

The Sargents, in July 1929, offered the Sargent School to the administration at Boston University.

The gift was accepted by Boston University under the condition the name remain unchanged and instruction be continued in the spirit of its founder.

Influencing Basketball’s Creation

The roots of basketball, and the popularization of basketball among Blacks, can be traced back to Sargent, according to Black Fives Foundation founder and executive director Claude Johnson, and Sargent’s time at Harvard courtesy of Luther Gulick, one of Sargent’s most important students.

Gulick, who would later accept employment with the Young Men’s Christian Association, better known as the YMCA, climbed the ranks, according to Johnson, at the organization and was appointed as head of the physical education department at the School of Christian Workers (later known as the International YMCA Training School and then Springfield College) in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Before long, a new instructor by the name of James Naismith came under Gulick’s supervision in the early 1890s.

Gulick wanted to invent a new sport to be played indoors during the North’s cold winter months.

He toyed with some aspects of the game, according to author Nelson George in his book “Elevating the Game: Black Men and Basketball,” and believed the new sport should include elements of existing sports.

Gulick assigned two of his YMCA instructors to devise the game, though both failed.

Naismith received the assignment next, George detailed, and was told he had two weeks to invent the sport with Naismith successfully completing the assignment “according to legend, on the fourteenth day.”

One could certainly argue basketball’s creation is thanks, in part, to Sargent and his innovative physical education courses at Harvard.

Sargent’s influence on basketball does not stop at the YMCA though.

Edwin B. Henderson, a young Black teacher from the racially segregated District of Columbia public school system, enrolled in Sargent’s program, in 1904, to “receive state-of-the-art training on how to become a physical education instructor,” Johnson chronicled.

“Henderson instantly saw the potential of this relatively new game called ‘basket-ball,’” detailed Johnson. “After finishing Sargent’s course he returned home to promote the game. However, according to Henderson, ‘basketball was at first considered a ‘sissy’ game, as was tennis in the rugged days of football.’ Not for long. Within five years there were dozens of African American teams and the game’s popularity among blacks soared.”

Henderson, an inductee of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, is credited, according to Johnson, as being the first to introduce the sport to Blacks on a wide-scale organized basis and has been hailed the “Grandfather of Black Basketball.”

Introducing Field Hockey

The sport of field hockey’s introduction to the United States was granted, reluctantly, by Sargent in 1901 during his time at the Harvard Summer School.

Constance Mary Katherine Applebee, at age 29, enrolled in Sargent’s summer program and staged a field hockey demonstration for her classmates.

She explained the basics and object of the game and, lacking the proper equipment, used wands and a dumbbell to demonstrate the sport.

Though the game was controversial for providing an avenue for women to participate in a more physical sport — Gulick was among those who rejected the sport decrying athletics for women as merely a form of recreation and pleasure, not a form of public competition as it was for men — the sport rapidly gained traction with colleges catering to women.

Applebee dismissed the criticism and held steadfast her in belief that if competitive athletics could teach men teamwork, sportsmanship and character — not to mention help them physically — the same would be possible for women.

Vassar College Director of Athletics Harriet Ballentine, a classmate of Applebee’s at Sargent’s school, invited Applebee to explain and demonstrate the sport at her institution that fall.

Shortly thereafter, invitations rolled in from Smith, Wellesley, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe and Bryn Mawr. (She would soon accept employment at Bryn Mawr and remained there until her retirement in 1929, coaching the sport informally until her death in 1981 at the age of 107.)

Applebee first garnered media attention for winning several prizes at Sargent’s summer program, and later continued to make headlines as a pioneer of field hockey’s presence in the United States.

Sargent’s Strength Tests

As part of his work at Harvard, Sargent developed a variety of strength tests.

The intercollegiate strength test was developed in 1886 and adopted by the College Gymnasium Directors Society in 1897, according to Boynton, and tested the strength of one’s back, legs, forearm, lungs and upper arm (through push ups and pull ups) to develop a total strength school. Standards for athletes of different sports were established, Boynton detailed, and the test was used by numerous higher education institutions around the nation.

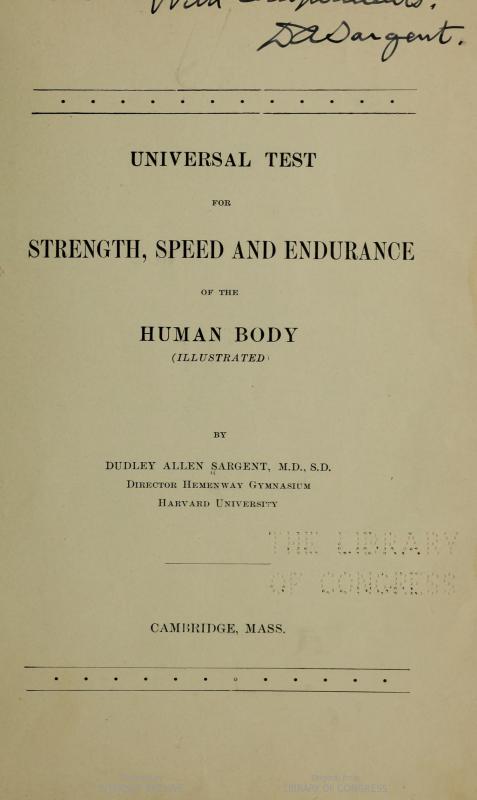

Sargent also developed, in 1902, the universal test for strength speed and endurance which included exercises for the abdominal muscles, arms and back, arms and chest, back and hamstring muscles, calf muscles, and thighs. The output data determined one’s speed, strength, and endurance combined, Boynton detailed, “or your physical fitness or efficiency.”

Perhaps the most known strength test Sargent developed is the one still being used by professional football and basketball players today — the vertical jump test.

As one of six standard workout drills used at the National Football League draft combine to evaluate and compare skillsets of college players hoping to embark on a professional football career, the vertical jump test has been described as “one of the more important drills” at the combine.

“This is far more than just a measurement as to how high a player can get, but rather a show of how strong their legs are and the possible burst they get from that set of muscles,” wrote Alexis Chassen, a SB Nation reporter. “The drill requires the combine attendees to start flat-footed with their arms extended above their heads to first measure their reach. Once this is established, the player jumps as high as he can, as indicated by a series of flags.”

Sargent’s Importance

Sargent, and his legacy, is detailed in a variety of ways by those who have studied him and his work.

Fred Eugene Leonard, an Oberlin College professor, described Sargent, in his 1923 book “A Guide to the History of Physical Education,” as a “man whose stimulating and molding influence upon physical training in American colleges [...] was to be more potent and more widely felt than any other that can be named.”

A special collection exhibition by Barbara Ward Grubb and Emily Houghton for the Bryn Mawr College Library cheered Sargent as one of the “most-respected advocates of physical fitness and purposive exercise for American women” during the nineteenth century.

The website for Boston University College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College notes how Sargent — “a 19th-century educator, visionary, and inventor” — helped change the belief that strengthening the body was considered beneath the dignity of educated men, and even opened the field up to women.

“By emphasizing training for all students, not just athletes, he largely created the discipline of physical education,” the BU Sargent College website reads. “He also built a reputation as an innovator by developing exercise machines that even weak and disabled individuals could use, thanks to pulley systems with adjustable weights. At his Sargent School, students learned training techniques to strengthen and improve the physical abilities of all people.”

Harvard, when hiring Sargent, viewed the Belfast native as “one of the leading experts in his nascent field,” according to academic Dr. Carolyn de la Peña (now Carolyn Thomas).

In fact, Shurley noted how Sargent was able to provide legitimacy to the field through his work.

“Sargent helped to legitimize the field by associating it with Harvard, by working to give it a scientific foundation, and he was exceptionally influential because the students he trained developed into transformative figures themselves at universities across the country (and the YMCA) and passed some of his philosophy on to their own students,” stated Shurley.

The landscape of the field of medical education in the United States at that time provided the perfect opportunity for Sargent to shape the field’s future as we know it today.

“When Sargent started at Harvard, American medical education was undergoing significant changes, moving from an understanding of physiology based on Hippocratic ideas of balancing humors (the philosophy under which Sargent would have trained), to a more scientific understanding of physiology, based on experimentation,” said Shurley.

de la Peña described Sargent in a journal article, “Health Machines and the Energized Male Body,” as a man who worked to codify a system of mechanized physical science with individuals building their bodies, through machines, to a state of maximum physical energy.

“Sargent, one of the first creators of systematic methods for mechanized physical training, helped to make possible the quantum advances in athletic performance that have resulted from twentieth-century machines such as the SB II racing bike or the Cybex training system,” de la Peña wrote.

Modern society views machines, according to de la Peña, as tools to improve physical performance — casual users use machines to build arms to lift more and legs to run faster, whereas athletes use machines to surpass human limits.

These views are opposite Sargent’s beliefs, de la Peña detailed, as he envisioned machines as celebrating the limits of the human body rather than surpassing those limits.

“For Sargent this meant developing a complex system of machines and measurements which, when combined, allowed every man and woman to reach a universal ‘perfect’ muscular form,” wrote de la Peña. “Sargent saw the ultimate goal of machine training as taking the body to a state of health and equilibrium. Only machines, he argued, could build a body of sufficient muscular strength to handle the increasing mental efforts of twentieth-century life.”

During his five decades devoted to physical education, Sargent influenced strength training beyond the confines of the Harvard institution, de la Peña noted, as he trained roughly 3,000 students representing 1,000 institutions during his time at Harvard who would then shape fitness programs across the nation.

In addition to Gulick’s aforementioned influence from his time under Sargent, de la Peña noted the YMCA, under Gulick, purchased Sargent’s developing machines and adopted his measurement system to allow thousands of men and women to build their bodies and gauge their progress.

On top of the thousands using his system via the YMCA, Sargent estimated, in 1890, his machines were being used by more than 100,000 people across 350 institutions across the nation, de la Peña detailed.

“The proliferation attests to the dramatic change that physical training and physical evaluations had undergone over the half century preceding 1920,” de la Peña wrote. “By the twentieth century, it was commonplace for students to exercise on machines.”

Perhaps Sargent’s significance as a historical figure can be epitomized by Shurley: “His emphasis on the importance of physical training was extraordinarily influential.”

Reach George Harvey at: sports@penbaypilot.com.

Event Date

Address

United States