Unseen by the naked eye

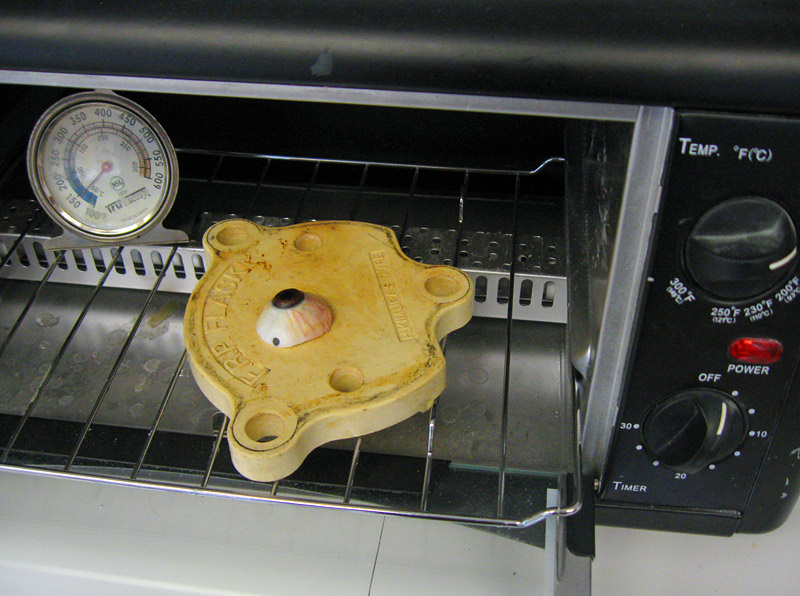

A prosthetic eye bakes in a toaster oven at Boston Ocular Prosthetics in Jackson. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A prosthetic eye bakes in a toaster oven at Boston Ocular Prosthetics in Jackson. (Photo by Ethan Andrews) Ottie Thomas-Smith, left, works alongside apprentice Lily Cross. (Photo by Ethan Andrews

Ottie Thomas-Smith, left, works alongside apprentice Lily Cross. (Photo by Ethan Andrews A display in the waiting room of the Boston Ocular Prosthetics office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A display in the waiting room of the Boston Ocular Prosthetics office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews) Jolene Bryant of Knox paints sclerae (whites) and irises for prosthetic eyes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Jolene Bryant of Knox paints sclerae (whites) and irises for prosthetic eyes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews) A prosthetic eye bakes in a toaster oven at Boston Ocular Prosthetics in Jackson. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A prosthetic eye bakes in a toaster oven at Boston Ocular Prosthetics in Jackson. (Photo by Ethan Andrews) Ottie Thomas-Smith, left, works alongside apprentice Lily Cross. (Photo by Ethan Andrews

Ottie Thomas-Smith, left, works alongside apprentice Lily Cross. (Photo by Ethan Andrews A display in the waiting room of the Boston Ocular Prosthetics office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A display in the waiting room of the Boston Ocular Prosthetics office. (Photo by Ethan Andrews) Jolene Bryant of Knox paints sclerae (whites) and irises for prosthetic eyes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Jolene Bryant of Knox paints sclerae (whites) and irises for prosthetic eyes. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)JACKSON – The blue and white sign outside Boston Ocular Prosthetics is clearly visible from Route 7, but it doesn’t stand out. Nor does the Latinate name call attention to itself, or the nondescript building behind a screen of trees.

It’s all fitting of a business where the best work goes unnoticed.

Ocularist, anaplastologist and owner of the business Ottie Thomas-Smith makes what in less modest and technologically-advanced times would have been called glass eyes. They aren’t made of glass anymore, and haven’t been for as long as she's been in the business, which is about 40 years.

On recent weekday, the fluorescent-lit work rooms of the Jackson office smelled of acrylic resin, the material now used to make prosthetic eyes. Thomas-Smith and two assistants painted irises and traced capillaries onto sclerae (whites), matching them to the individual shades of her clients, many of whom are from the Boston area. Thomas-Smith has two offices there, and a third in Portland.

Looking around the work area at Boston Ocular Prosthetics, one thing that jumps out is that artificial eyes, unlike their slapstick counterparts, are not complete globes. The real things are closer to a hemisphere with indentations in the back to match the peculiarities of patient's ocular cavity.

Since 1984, however, all the production work has been done in Jackson.

Thomas-Smith originally came here visit her secretary who had moved to the area. Almost 30 years later, she is still making bi-weekly trips to the home office, but said it's worth it to be away from the action.

"There's not the horrible interruptions," she said. "I've worked in Boston and you can't get anything done. Here it's nice and quiet."

Boston Ocular Prosthetics also does a wide range of flesh-simulating prosthetics including orbital implants (around the eye), ears, noses and fingertips. A display case in the waiting room shows, among other examples, a plaster face with and without a hemi-facial prosthetic — the false eye area and cheek covering a massive concavity in the face of one of Thomas-Smith's patients. Most of the maxillo-facial prosthetics, as they're called, conceal such cavities, typically the result of surgery to remove a cancerous tumor.

Thomas-Smith's business card identifies her by a pair of medical-sounding titles, and on the day I visited she wore a blue lab coat that could be mistaken, at a glance, for scrubs. The dimly lit waiting room of her office resembled that of a doctor or dentist.

But the back rooms where all the work is done were different; less like exam rooms than a laboratory or art studio. The counters were crowded with molds used to cast prosthetic eyes. One of these baking in a toaster oven between glazes. An assistant buffed another eye against a fluffy white disc stained green with polishing compound. In an attached room, small jars of pigments, fine-bristled paint brushes and magazine clippings of eyes were set out on tidy work tables.

"You really want an art background because you're primarily painting and sculpting," she said. "Those are the requirements."

Thomas-Smith had just that when she started her own career prosthetics. It was during the Vietnam War and the Veteran's Administration was recruiting artists. Thomas-Smith, who had just graduated from Rhode Island School of Design, took a job with the VA and went to work in Manhattan at the administration's Prosthetics Treatment Lab. She was later transferred to Boston. Along the way, there was a four-year training program, she said, but it was all on the job.

"You watched and learned," she said.

After taking some private patients on referrals, Thomas-Smith went into private practice in the early '80s under company name she uses today.

Looking around the work area at Boston Ocular Prosthetics, one thing that jumps out is that artificial eyes, unlike their slapstick counterparts, are not complete globes. The real things are closer to a hemisphere with indentations in the back to match the peculiarities of patient's ocular cavity. Sometimes the prosthetic can be connected to muscles in the eye so that it moves to a certain degree. Aside from an annual polish to remove dirt — or occasionally an accumulation of salt from tears, Thomas-Smith said — the eyes stay in, day and night.

Blown glass eyes used before World War II were hollow and fragile enough that they could break with a sudden change of temperature. Thomas-Smith had several in a platic container. They looked like eggs from a small bird. One had partially shattered.

For comparison's sake, she dropped a spare acrylic eye on the floor, stepped on it and scraped it back and forth with her foot, then picked it up, still apparently intact.

"You probably wouldn't want to do that with a real one, but you get the idea," she said.

Facial prostheses, Thomas-Smith's other specialty, are either held in place by existing bone, as in an orbital implant, or are clipped onto metal posts implanted in the bone. The latter works well for ears.

Thomas-Smith's patients may have suffered dog bites or been in fires or explosions. Some are foreign nationals who had surgery in Boston but didn't have access to prosthetics in their home country. Several had been in incidents that made headlines in Southern New England, though she asked that the events not be named on the chance that doing so could identify her patients.

It was a fair request, given the nature of the business.

"They just don't want people to notice," she said. "They want to go about their lives with nobody staring and asking questions."

Penobscot Bay Pilot reporter Ethan Andrews can be reached at ethanandrews@penbaypilot.com

Address

404 Moosehead Trail

Jackson, ME 04921

United States