"To be interested in the popular culture of contemporary America is to be interested in our popular architecture; the architecture of those buildings in which we live or work or enjoy ourselves. They are not only an important part of our everyday environment, they also reveal in their design and evolution much about our values and how we adjust to the surrounding world" – J.B. Jackson

The garage is a case in point. The word garage is of French origin and it means simply storage space. The use of the French indicates the exotic and expensive nature of early motoring. Part of the expense was retaining a chauffeur who had to be housed with the new machine.

The logical location for this new space was the existing stable or barn, located at a safe distance from the house, in case dangerous fumes should asphyxiate the owners. However acids emanating from the stables damaged the brass trim and paint on the cars, so a new autonomous building type soon emerged.

Meanwhile, thousands of miles away from the luxury world of gentleman's sports cars, Henry Ford was building the first Model T in his friend's coal shed in Detroit. The first garage door was created when he realized he needed to punch a hole in the wall to get his new car outside.

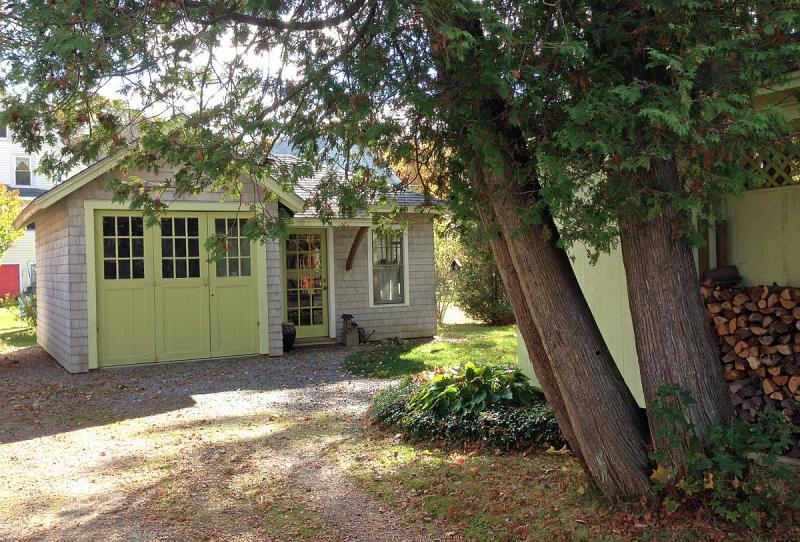

The Model T Ford was the beginning of the democratization of car culture. The first Americans to see their practical value were farmers, country doctors and deliverymen. They needed a practical, reliable and affordable means of transportation. The garages that evolved to house these vehicles were simple boxes, only just big enough to keep weather off, and often relegated to the back yard, along with the trash, the doghouse and the laundry.

After World War II, the rapid suburbanization of America paralleled the growth of the car industry. Soon every middle class family owned a car. It took a while for the home building industry to catch on, but the wider suburban house lots had enough street frontage for attached garages to be easily added on to existing homes. Families acquired two or three cars and home deliveries became a thing of the past. Garages grew bigger as they stored not only the cars but freezers, washing machines and clothes dryers. Sometimes the lawnmowers and sports equipment elbowed the car back out onto the driveway. A basketball hoop was added to the gable of the garage - the asphalt driveway was a perfect ball bouncing surface.

However, the garage was much more than an attached storage shed.

Recreation was becoming a cultural imperative in our family lives and the garage was the container that enabled our domestic aspirations to be realized. Millions of ordinary Americans repurposed utilitarian car storage into a place of possibilities. In an increasingly abstract work world, the workshop bench running along the back wall of the garage was a place to feel our connection to concrete reality.

Vehicles were repaired, boats stored, wood stacked and seedlings started. It became the ubiquitous man cave - a place to drink beer and discuss football with the guys, sitting on plastic lawn chairs, a world away from the ordered domesticity of the house.

How is this vernacular place going to evolve in the future? Will electric technology bring the car into the living room? Will it become increasingly important in a digitized world as a place to connect with what feels real to us?

As designers, we would like to put in a plug for un-designed spaces - spaces that enable us to play and explore without inhibition or specificity: a place of possibilities.

Chris Wohler came to Camden 20 years ago after living in New York for 24 years. She has a Bachelor of Arts in history from Cornell University and a Master of Architecture from Columbia University. She has taught at Ball State University, Parsons School of Design and Columbia University. Her design practice, Breathing Space, encompasses everything from architectural design to retail merchandising.

Chris Wohler came to Camden 20 years ago after living in New York for 24 years. She has a Bachelor of Arts in history from Cornell University and a Master of Architecture from Columbia University. She has taught at Ball State University, Parsons School of Design and Columbia University. Her design practice, Breathing Space, encompasses everything from architectural design to retail merchandising.

She likes blackbirds, crosswords, babies, Miles Davis, avocados, quantum physics, Robert Frank, chartreuse, Puccini, roses, graphite drawings, the collaborative process, Great Danes, Patti Smith, gardening, J.S. Bach’s Suites for Solo Cello, architectural plans, movies, Philip Pullman, cooking with friends, everything by Beethoven, New York City and her two sons who currently live there. Reach her at breathingspace2@gmail.com.

Rosie Curtis lives in Camden and teaches architecture at UMA.

Originally from England, she has been designing and building in Midcoast Maine for the last 20 years, although she indulges in a spot of work for a British engineering firm now and then. She holds two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree in architecture and has been interested in the built environment her whole life. She believes that design is fundamentally about things working well and looking good. Her two kids are fed up of hearing her pontificate about all things design related and hope this column will provide a channel for her endless wonderings. Reach her at rosie@fairpoint.net.

More Design Notes:

• Design Notes: An introduction

• The Welcome Mat: The story of front and back