MaineHealth/Tufts research into long-term effects of Lyme Disease begins enrolling participants this month

PORTLAND — While well into a Lyme vaccine study, MaineHealth Pen Bay Hospital, and its lead department, the MaineHealth Institute for Research, is embarking on another tick-borne disease study. This new research, initiated in conjunction with Tufts University School of Medicine, will focus on why some patients fail to fully recover from Lyme disease after receiving standard courses of antibiotics.

Pen Bay Hospital will be enrolling participants this month. The project is funded by a $20.7 million grant from the federal National Institutes of Health, and according to Dr. Rob Smith, director of the Vector-Borne Disease Lab at the MaineHealth Institute for Research, that funding remains intact. MaineHealth is to receive $3.1 million over the life of the grant for its role in the study.

MaineHealth doctors' offices associated with Pen Bay Hospital will be enrolling participants who are over age 18, and who are at the earliest stage of diagnosis of Lyme disease. A likewise enrollment will take place at Southern Maine Medical Center in Biddeford. The study team plans to recruit a total of 1,000 patients as soon as they receive their diagnosis of Lyme disease and follow them over the course of a year.

Participants will be limited to those newly diagnosed with Lyme disease so that researchers can examine the disease from its earliest stages.

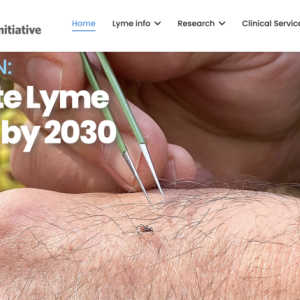

Tick season is now in full swing, with nymphs as well as adult ticks latching onto humans and animals in the woods and tall grass. The Midcoast and Penobscot Bay region — most prominently Knox, Lincoln, Waldo, and now Hancock, counties — continues to be Maine's epicenter for exposure to the tickborne bacteria, parasite and virus that can cause grave illness.

According to the state's Tick Lab, there are: "15 different tick species that have been found in Maine, though not all are permanent residents. Some may arrive in the state on wildlife hosts and do not establish viable populations. Other species have thrived in Maine and are now widespread throughout much of the state."

Last October, the Maine Center for Disease Control said it had recorded in 2024:

- 2,544 cases of Lyme disease

- 888 cases of anaplasmosis

- 265 cases of babesiosis

- 19 cases of hard tick relapsing fever

- 4 cases of Powassan encephalitis

By December, 2024, the number of Lyme disease cases for the year had increased to 3,218, breaking the annual record.

Five to 20 percent of those who recover from acute Lyme disease symptoms after treatment suffer persistent illness with symptoms similar to those of Long COVID. It is not clear what the causes are, said MaineHealth.

According to MaineHealth, symptoms of, "untreated Lyme disease include a rash (often, but not always in the shape of a bullseye), fever, chills, fatigue, muscle and joint pain." Symptoms of longterm Lyme disease include fatigue, widespread pain, and cognition issues.

“The study will incorporate the latest scientific advances in microbial and host genetics and measures of immune response to infection,” said Dr. Smith, who is the clinical operations lead for this study. “We’re also hoping that by following patients from their earliest diagnosis, we will create a robust data bank that will lead to new avenues for treatment of persons with persistent symptoms such as fatigue, pain and brain fog.”

In a description of the study, MaineHealth said, "The goal is to understand mechanisms causing delayed recovery after treatment and to search for biomarkers that are different in patients who go on to have persistent Lyme disease symptoms from those who fully recover from the disease."

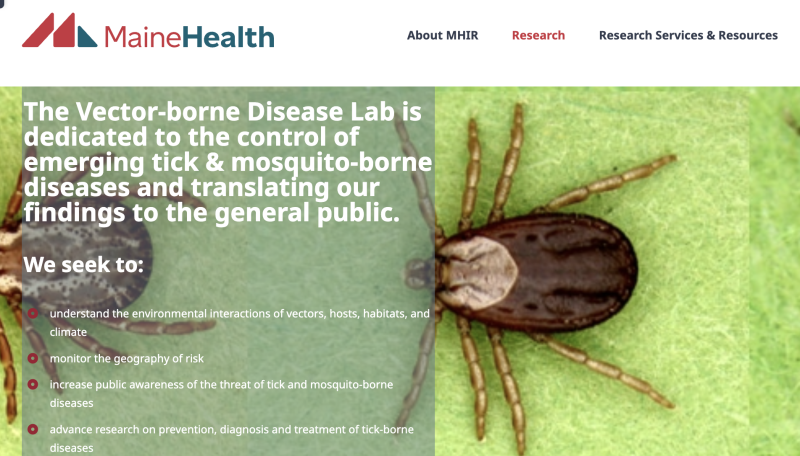

Dr. Smith is an infectious disease physician who researches molecular epidemiology and ecology of emergent vector-borne diseases (Lyme, Babesia, Anaplasma, Powassan Virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus), as well as clinical recognition and diagnosis of emergent vector-borne diseases. He was the founding director of the Virology Treatment Center at Maine Medical Center and is the cofounder and director of the Vector-borne Disease Laboratory. He also teaches at Tufts, where there is alo ongoing research into tickborne illness, and remedies.

Along with the current two tickborne illness research studies, the MaineHealth Institute for Research, based in Scarborough, is also in the middle of a babesiosis study. A collaboration amongst multiple health care center in the North East has aggregated a large data set put to use. That study involves patients who have been hospitalized because of babesiosis.

"Babesiosis is a disease caused by tiny parasites that infect red blood cells," according to the Maine CDC. "Babesiosis is most commonly transmitted to a person through the bite of an infected deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Babesiosis is also spread through transfusion of contaminated blood. In rare instances, a mother can pass babesiosis to her child during pregnancy and delivery."

And, the MaineHealth Institute for Research is studying the rare and lethal Powassan virus, also carried by the deer and woodchuck ticks.

Powassan patients may have a loss of coordination and seizures, and the infection can cause swelling of the brain (encephalitis) or swelling of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord (meningitis). For those with severe symptoms, about one out of every 10 cases ends in death, the Maine CDC said. "About half of survivors have permanent brain damage."

"We have some ideas in mind for looking at Powassan," said Smith. "Because it is so rare, you are not going to be able to launch a large clinical study right now. Even though the cases are increasing throughout the North East, they are rare in terms of number. We are interested in trying to identify if there are people who get Powassan infection with much more minor symptoms, so they never get diagnosed."

Dr. Smith has been researching vector-borne illness since 1988 in Maine. He was part of the Monhegan Lyme Disease project of the late 1980s, which began with basic surveillance of the tick. That Monhegan project eventually resulted in the killing of the deer herd on that island in attempts to reduce the deer tick population.

"We started this work 30 years ago when it was a few ticks in a few places in Maine, and one disease," said Smith. "Now we have a lot more complicated situations. It is keeping us very busy."

Research encompasses ecological field work to clinical studies. Given the dynanism of the Maine landscape, the rise and fall of rodent populations, deer census and bird migrations, plus climate change and environmental cycles, the information gleaned is not static.

"That is why having multi-year studies can be helpful in sorting that part out," said Smith.

One certainty, however, is that ticks now have a significant influence on public health, and safe outdoor activity.

In April, the Tick Lab reported that in 2024 it had sampled over 4,700 ticks from all over Maine, with more than 3,500 of them being deer ticks. Lab tests showed that 41.5% of the deer ticks analyzed carried Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease; 12% carried Babesia microtic; 9.7% had Anaplasma phagocytophilum; and, 1.1% carried Powassan virus.

Reach Editorial Director Lynda Clancy at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com; 207-706-6657