Coastal Farms enters 2013 a little wiser, still wide-eyed

The Coastal Farms and Food Processing management team, from left, Wayne Snyder, Jan Anderson and Tony Kelly in a portion of the company's 60,000 facility that was used last fall to process over a million pounds of frozen blueberries. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The Coastal Farms and Food Processing management team, from left, Wayne Snyder, Jan Anderson and Tony Kelly in a portion of the company's 60,000 facility that was used last fall to process over a million pounds of frozen blueberries. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Workers on the blueberry processing line shortly after Coastal Farms opened in August 2012. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Workers on the blueberry processing line shortly after Coastal Farms opened in August 2012. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The massive freezer used to store appliance-box-sized containers of blueberries and cranberries at a temperature of negative 15 degrees. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The massive freezer used to store appliance-box-sized containers of blueberries and cranberries at a temperature of negative 15 degrees. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

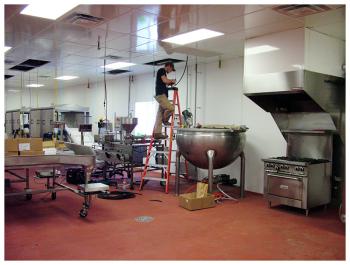

Ryan St. Clair of Arc Electric installs drop cords in the commercial kitchen in January. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Ryan St. Clair of Arc Electric installs drop cords in the commercial kitchen in January. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A vacant portion of the 60,000 square foot building that will likely be used to expand the commercial kitchen, visible at left. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A vacant portion of the 60,000 square foot building that will likely be used to expand the commercial kitchen, visible at left. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The Coastal Farms and Food Processing management team, from left, Wayne Snyder, Jan Anderson and Tony Kelly in a portion of the company's 60,000 facility that was used last fall to process over a million pounds of frozen blueberries. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The Coastal Farms and Food Processing management team, from left, Wayne Snyder, Jan Anderson and Tony Kelly in a portion of the company's 60,000 facility that was used last fall to process over a million pounds of frozen blueberries. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Workers on the blueberry processing line shortly after Coastal Farms opened in August 2012. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Workers on the blueberry processing line shortly after Coastal Farms opened in August 2012. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The massive freezer used to store appliance-box-sized containers of blueberries and cranberries at a temperature of negative 15 degrees. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

The massive freezer used to store appliance-box-sized containers of blueberries and cranberries at a temperature of negative 15 degrees. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Ryan St. Clair of Arc Electric installs drop cords in the commercial kitchen in January. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

Ryan St. Clair of Arc Electric installs drop cords in the commercial kitchen in January. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A vacant portion of the 60,000 square foot building that will likely be used to expand the commercial kitchen, visible at left. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

A vacant portion of the 60,000 square foot building that will likely be used to expand the commercial kitchen, visible at left. (Photo by Ethan Andrews)

BELFAST – Jan Anderson was serving on the City Council in 2009 when she first shared her vision of Belfast becoming a regional storage and processing hub for farmers and food entrepreneurs. Her hope was to convince her fellow councilors to invest in the idea as an economic development initiative.

What the city needed, she said, was a centrally located, state-of-the-art facility with abundant frozen and dry storage for local produce, a shared commercial kitchen, and the potential for a symbiotic relationship between the two.

She was essentially describing Coastal Farms Food Processing, the business she would open three years later, though at the time she had no intention of starting anything on that scale.

From her research she knew that a third of Maine’s farm businesses were located within 50 miles of Belfast, and that many of these had scaled back their production, growing only as much as they could sell at seasonal markets. A survey of farmers by the USDA-affiliated Time and Tide RC&D found that many would gladly grow more if they had a way to store the produce.

A similar hurdle existed for food entrepreneurs. Many lacked the equipment and space to make the leap from small-scale production for local markets to supplying large-market buyers like Whole Foods.

Anderson’s idea made sense on paper, and she promoted it heavily in her last year on the Council, but for whatever reason it didn't take hold.

When she lost a bid for re-election in 2009, she remained a proponent of her idea, but was unsure if she wanted to lead the project. In an article published in a local newspaper, she expressed her desire for someone else to take the idea and run with it.

The article caught the eye of Tony Kelly, a 25-year veteran of Maine's frozen food storage industry. He contacted Anderson with a proposition: a joint venture with commercial blueberry processing on one side and local food storage and a commercial kitchen on the other.

For Anderson, the collaboration meant buying into an industrial food-processing venture to support her vision of a resource for local farmers and small businesses. It was a practical decision that made all the rest of it possible.

“You have to be able to convince an investor the you’re going to pay them back,” she said. Blueberry processing with its successful hundred-year history could do just that.

Anderson and Kelly brought on Wayne Snyder, a retired commercial developer, to help raise start-up capital and manage some of the back office details of the new business.

The group raised $1 million through sales of company shares to private investors, got another $1 million in financing from Farm Credit of Maine and signed a lease on a 60,000 square foot portion of the former Moss building on Route 1.

With the exception of a new sign, the exterior of the building looks much the same as it did when Moss was there. But the interior transformation has been dramatic.

A portion of the building was retrofit with a gymnasium-sized freezer, capable of holding 15 million pounds of blueberries at negative 15 degrees Fahrenheit. Outside the freezer stood an assembly line of equipment capable of cleaning, sorting and flash-freezing blueberries and cranberries.

In an adjacent section of the building a massive bank of coolers and smaller freezers was installed to store produce and processed foods. Additionally, a 10,000 square foot portion of the building was given over to a commercial kitchen, outfitted with utility hook-ups customized for three “anchor tenants” along with enough kitchen basics — sinks, stoves, shelving — to accommodate a range of small-scale processing and contract work.

On a day in mid-August 2012, a tractor-trailer loaded with Canadian blueberries arrived at Coastal Farms. The plant was still hiring, but workers were on hand for what would be the first real test of the blueberry processing line.

Speaking earlier that week, Kelly had referred to the month ahead only half-jokingly as “the horrors.” Once the shipments started coming, a tractor-trailer would arrive every 12 hours. Workers would feed berries into the production line around the clock at a rate of one suitcase-sized crate every fifteen seconds, an interval announced by a buzzer mounted on the wall near the beginning of the line.

At the other end, frozen blueberries would stream off the end of a conveyor belt into massive cardboard boxes bound for the freezer. Later these would be portioned into 30-pound boxes and shipped out by refrigerated truck.

Coastal Farms missed the Maine blueberry season last year. Even so, an abbreviated version of “the horrors” was more than made up for by the inevitable growing pains of fine-tuning a new facility. There were berries of the wrong grade, conveyor belts that slipped and broke, and other mechanical problems that plagued the line.

“We had all kinds of fun this go round,” Kelly said in January. “So we should be all set for next year.”

Despite mishaps, the 45 employees who worked the line through November put away 1.3 million pounds of blueberries and 240,000 pounds of cranberries. Kelly said he’s shooting for 3 million pounds of blueberries and 2-3 million pounds of cranberries in 2013.

Based on those numbers, he has had to turn down some requests for space in Coastal Farms’ megafreezer. Plans are in the works to add a second freezer outside of the building tapping into the existing capacity of the current condenser.

For all the hustle of the berry season, by mid-January the operation was mostly tucked away. In the large freezer dozens of appliance-sized cardboard containers were stacked four-high. The assembly line was dismantled, cleaned and pushed to one side of the room, awaiting next year's harvest.

Focus had shifted to the commercial kitchen where the three “anchor tenants” — Jeffrey Wolovitz of Heiwa Tofu, Brian McCarthy of Magic Dilly Beans and Julie Romano, of Julie Ann’s Outrageous! Foods — were either up and running or about to be.

(PenBay Pilot talked to the owners of these businesses for a series of forthcoming articles.)

Others businesses, including Tournesol, the Chocolate Drop Candy Shop and Cheryl Wixson’s Kitchen had used the kitchen or were planning to.

Anderson shied away from details about specific financial agreements — as did the commercial kitchen’s tenants — but she said her initial idea of renting kitchen space by the square foot didn’t make sense in practice, so she swapped it for a system that factored in utilities and some of the specialized equipment at an hourly rate.

Space within the smaller coolers that were built for raw produce and processed foods is currently available to rent by the pallet. Some of the food producers from the commercial kitchen said they plan to use the on-site storage as an adjunct to their business. Wixson’s Kitchen has a pallet; Chase’s Daily has several.

With regard to new tenants or others interested in using the kitchen or the dry or cold storage, Anderson said that side of the business is evolving based on what farmers, restaurant owners, food entrepreneurs and others need. Recently Coastal Farms steamed and froze 700 pounds of broccoli for the food service of Regional School Unit 20 as a test run.

Anderson said she’s open to any proposal.

"We had a lot of people coming in wanting to do something with their land,” she said. “Now they have the opportunity.”

Whatever tensions might arise out of having to share resources seem so far to have been muted amid the excitement of the larger venture. From the tradesmen installing steam pipes and electrical wiring to the food entrepreneurs and members of the management team, inside the nondescript brown building, there’s a palpable sense that something is happening and everyone has a small stake in it.

“We’re partnering not in a legal way, but in an ethical way,” Anderson said. She was referring to the food entrepreneurs, but she could have been talking about anyone else involved with Coastal Farms. “If they’re successful, we’re successful,” she said.

A representative of Whole Foods visited Coastal Farms recently, according to Anderson and several of the tenants, and was said to have talked encouragingly with the food entrepreneurs, saying in effect: call us when you’re making enough to stock one of our stores.

Meanwhile, Anderson, Kelly, and Snyder are making plans for expanding all three facets of the business.

According to Kelly, there’s been no shortage of interest in Coastal Farms. The challenge has been keeping up with demand.

“This thing took off like a rocket with no end in sight,” he said.

Contact Ethan Andrews by e-mail at news@penbaypilot.com

Event Date

Address

248 Northport Avenue

Belfast, ME 04915

United States