This Week in Lincolnville: Once Again, April Doesn’t Disappoint

It’s spring, isn’t it? Everywhere but here. Six inches of heavy snow cover the unfolding tulip leaves, bury the crocuses and bend down Don’s beloved daffodils. Mine have wisely held off even budding up here in Sleepy Hollow, with a climate zone all to itself. I think of it as Zone -5, always days behind the neighbors, warming up late, freezing early.

I had, however, foolishly planted the sweet pea seedlings in the canoe out front, expecting to get a jump on the season. Poor things! Wally always called an April snowstorm ‘poor man’s fertilizer’, taking nutrients down into the soil as it melted.

A power outage is such an assault on the order of things, especially coming in the middle of the night, a nasty surprise to wake up to. Especially coming in the middle of this shut down-pandemic- quarantine from seeing friends. I’m reminded of the morning, not long after Wally died, when I awoke to an outage. As vulnerable a time as it was anyway, how could I cope with more?

And you do. And then I did.

Finding ourselves without lights, an impotent water system, and for many, no heat, leaves us momentarily helpless. But then, common sense kicks in. Out come the kerosene lamps, the 5 gallon pail of water that lives behind the toilet (sweet flush!) and a nice birch log, all crinkly dry bark, tossed onto the coals and the universe swings back into focus.

These, of course, are the scribblings of someone sitting with a lined pad of paper and a pen next to the quiet, steady flame of an old lamp. A funny time for a writer long used to assembling words with a keyboard, tap tap tap. Forming the words (use your best cursive I told the 8-year-old, signing Easter cards to friends and neighbors these Corvid-19 days) in my own rusty cursive, sitting here in the little pool of light, words that seem to come more directly from the heart, physically formed by hands that were Jack’s age when they learned the motions.

Hands are what make us human, especially the thumb that allows us to grasp a tool such as a pen. Though we use our hands every day to do a thousand things, forming our very thoughts through a series of squiggly lines we call writing may be the most meaningful use of all.

Just yesterday, when my world was orderly, when my rooms were well lighted, when the faucets reliably produced hot and cold water, when a touch on my keyboard brought the whole world up onto the screen in front of me, I was deeply involved in a very different world. The world of a man who lived 150 years ago, who died before I was born, a man I never could have met.

Arno Knight lived on the land where his great-grandparents, Nathan and Lydia Knight built their log cabin in 1770, becoming the town’s first permanent settlers. The cabin was near the intersection of Belfast and Joy roads; the Historical Society erected a sign there a while back. Arno’s farm, Maple Lawn, was located on the hill overlooking the marsh: 2078 Belfast Road.

Several years ago, when Brad Knight, Arno’s great-grandson was preparing to move with his wife, Linda, to Tucson, the Lincolnville Historical Society took those diaries on loan. Brad has carefully saved his ancestors’ papers – their letters, photos, and yes, those diaries. The LHS scanned hundreds of the family’s letters and other material at the time, but scanning the dozens of journals seemed like a daunting task.

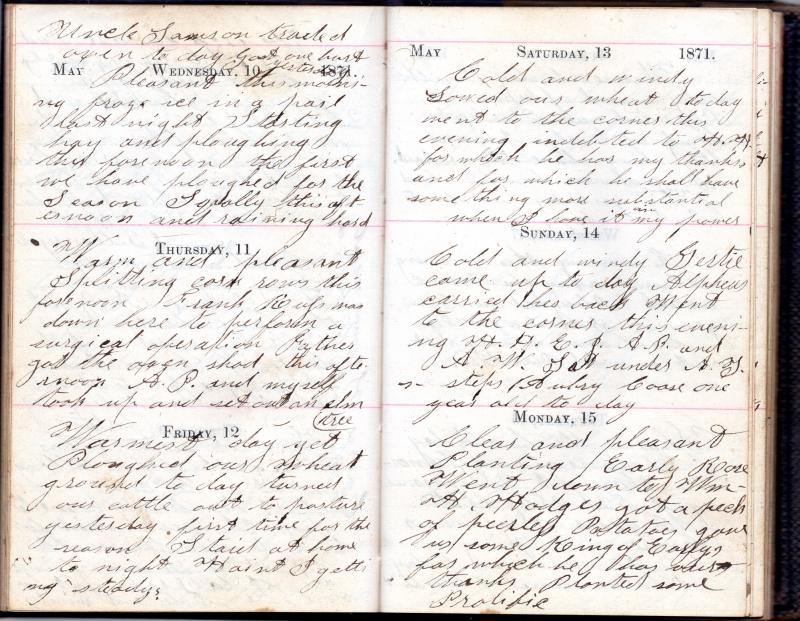

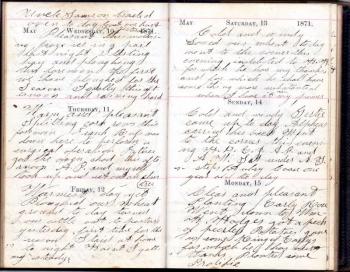

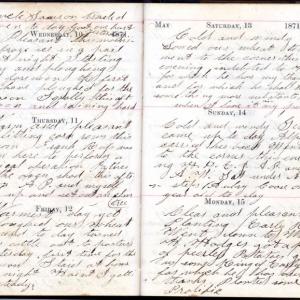

Then, a couple of weeks into the “stay at home” order, with an absolutely empty calendar stretching into the future, I finally began the long and, I feared, tedious task of scanning Arno Knight’s daily journals, some 60 of them, small, leather bound books that he wrote in nearly every day of his life starting when he was 21 years old.

Arno was a writer in the fullest sense, producing not just the record of his days’ work, but whole volumes of poetry and essays. A frequent purchase, which he recorded along with other expenditures, was a bottle of ink. Arno wrote with a steel nib pen, regularly dipping it into the bottle as he went.

Have you ever tried that? There’s a skill to it that must have come with practice. He rarely made any blots or corrections. And the very slowness of stopping to dip the pen must give the writer time to think about his next words. A far cry from auto correct, the copy and paste the modern writer has at her hand, enabling her to move material around with a tap of the key, checking spelling and the thesaurus without missing a beat.

What’s so valuable, so important about an obscure farmer’s musing about life in a marginally sustainable town far from any city, halfway up the coast of Maine? Journals, and Arno’s in particular, are fascinating for the way they take you inside the mind of a person living so long ago. Letters do it too, often with more personal emotion than the journals I’ve seen.

Sometimes I feel like a voyeur, reading over somebody’s shoulder, as he or she reveals secrets never meant for anyone but the intended recipient, or even just for himself. As I’ve often noticed, the letters and journals of childless people are more likely to survive and end up in the hands of someone like me, someone who mines them for historical detail, or is just plain curious about other people’s lives, than when a surviving son or daughter inherits them.

Or, as with Arno’s papers, the intervening two or three generations are cleansing; no one is still alive who would have any idea of the drama, the grudges, or unrequited love expressed in a packet of old letters or in a diary kept a hundred years ago.

The scanning has turned out to be anything but tedious. I look forward to spending an hour or two every day turning those little pages describing Arno’s days into electronic files that will be stored up in the Cloud.

I’m still in the 1870s when Arno was a young man, cutting hay, “ploughing” the fields, hoeing corn, planting apple trees by day and heading to the “Corner” in the evenings. Tom Sadowski tells me there’s may have been a tavern in the basement of the California House at one time. Perhaps the frequent notation on those evenings out “spent 5 cents on candy” refers to something else.

Or there may have been a dance at Billings Dance Hall, also in the Centre, as it was spelled then. On those nights Arno would report carrying Helen or Carrie or some other girl home, getting home himself at 3 or 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning.

Now that we have free access to the Library Edition of Ancestry.com and all the census records, it’s easy to look up these peripheral characters in Arno’s diary, to figure out where they lived, how old they were.

From the letters I scanned earlier I know that Arno left Lincolnville for Colorado and an ephemeral silver mine that never really panned out. He returned home after several years, married Olive Drinkwater from down the road, and spent the rest of his life in his childhood home, writing through the seasons, recording the weather, the planting, the harvesting, and the day to day dramas of his family life.

As for the daily dramas of our life here, we survived three days of having no power – what a pitiful drama compared to what’s going on all over the country and the world these days! And tomorrow I’ll dip into life 150 years ago, even as we all wonder how this particular drama we’re in will play out.

Town

The Selectmen meet remotely Monday, April 13 at 6 p.m. It will be live streamed through the town’s website.

Fire Department

Thanks to the Fire Department for supplying water for folks over the week-end. The ultimate insult when we lose power is the loss of water!

Strange Times

Thanks also to the businesses that are still supplying essentials via curbside service: The General Store, Dots, the Camden Deli, Aubuchon, Viking, Western Auto, Green Tree Coffee, and soon McLaughlin’s Lobster Shack which is opening in a few days. The Post Office and the Town Office can be accessed via phone or on line, and the school, of course, which delivers meals to children, and lesson packets, and Facetime teachers to students.

United Christian Church holds services every week via Zoom as well.

Please let me know if your business or service is still functioning in some capacity; I think we all want to support you in anyway we can. We’ll get through this ….

Event Date

Address

United States