Threads of Lincolnville history preserved with care

Some of the children's items on display at the Schoolhouse Museum in Lincolnville.

Some of the children's items on display at the Schoolhouse Museum in Lincolnville.

Wooden salmon wherry

Wooden salmon wherry

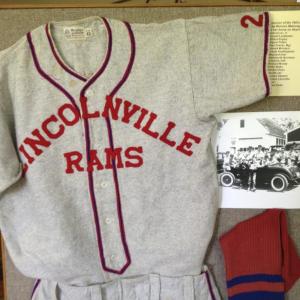

Lincolnville Rams uniform

Lincolnville Rams uniform

Handmade buoys

Handmade buoys

Shoemaking tools

Shoemaking tools

Kitchen tools

Kitchen tools

Tub for Saturday night bath and an old rocker.

Tub for Saturday night bath and an old rocker.

A lunchbox sits on one of the museum's school desks.

A lunchbox sits on one of the museum's school desks.

A doll on display

A doll on display

Washbasin and pitcher

Washbasin and pitcher

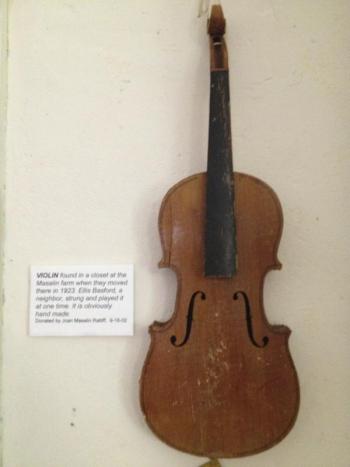

Violin found on the Masalin Farm.

Violin found on the Masalin Farm.

Wood cookstove with a display of items used for washing.

Wood cookstove with a display of items used for washing.

Some of the children's items on display at the Schoolhouse Museum in Lincolnville.

Some of the children's items on display at the Schoolhouse Museum in Lincolnville.

Wooden salmon wherry

Wooden salmon wherry

Lincolnville Rams uniform

Lincolnville Rams uniform

Handmade buoys

Handmade buoys

Shoemaking tools

Shoemaking tools

Kitchen tools

Kitchen tools

Tub for Saturday night bath and an old rocker.

Tub for Saturday night bath and an old rocker.

A lunchbox sits on one of the museum's school desks.

A lunchbox sits on one of the museum's school desks.

A doll on display

A doll on display

Washbasin and pitcher

Washbasin and pitcher

Violin found on the Masalin Farm.

Violin found on the Masalin Farm.

Wood cookstove with a display of items used for washing.

Wood cookstove with a display of items used for washing.

LINCOLNVILLE — On a recent Wednesday afternoon, Connie Parker stood in the back room of the Lincolnville Historical Society’s Schoolhouse Museum and examined an old, yellowed piece of paper filled with names written in hard to read script: Knox Woolen Mill, Hills, Babbs, Robinson, Pascal, Knowlton, all listed as investors in the proposed Penobscot Shore Line Railroad. The 2-foot-long document was dated October 9, 1890.

Parker, who works at the museum three days a week, said the railroad, which was never built, was planned to transport freight from Rockland to Camden. Several of the investors, all business owners, were listed as giving $1,000, a near fortune in those days.

According to Diane O’Brien, chairman of the Historical Society, the museum often receives old documents, photos and household goods of historical significance from people who find them while cleaning out an attic or basement or getting ready to sell a family home. The challenge is then to learn as much as possible about a particular item’s background.

“The focus of this museum is to attach people to things,” said O’Brien. “We want the old wood stove, for example, to mean something. Our focus is to gather the stories behind the things.”

Housed on the second floor of the restored 1892 Beach School building, the museum welcomes a steady flow of visitors in the summer who want to learn more about the history of Lincolnville. The old schoolroom, which still has its original blackboard, bell and woodwork, was used to educate students in grades one to eight until 1947 when the town built a consolidated school in Lincolnville Center.

The museum is filled with items reflecting the town’s rich history. An old treadle sewing machine sits on a table near a rack filled with spools of thread; above it on the wall is a violin that was found in a closet at the Masalin Farm in 1923. To the right is a wood cookstove with an agitator for hand washing sitting on top. Fishing and hunting gear, farm implements, a baseball uniform from the 1950s, a 19th century sea chest, and a bobsled are just some of the many other treasures on display. A handcrafted salmon wherry sits on the floor by the window and next to it is an old wooden sleigh.

Posters and photos with the displays describe things such as the town’s once thriving lime industry, productive farms and one-room schoolhouses. For example, there are photos of the farm that raised and shipped strawberries from Lincolnville Beach to Boston in the early 1900s. On one poster, three cousins share memories of Saturday night bath time on Youngtown Road in the 1930s. And there is a display of Native American artifacts recovered from sites along Ducktrap Harbor.

According to Parker and O’Brien, a large number of the town’s current residents are descended from its earliest settlers. The museum keeps genealogies of several of these families and has a substantial collection of books about local history, including two by O’Brien: Staying Put in Lincolnville, Maine 1900 - 1950; and Ducktrap: Chronicles of a Maine Village.

Parker, who started working at the museum about 10 years ago, said she got involved in the historical society when O’Brien, who helped found the organization in 1975, asked if she wanted to volunteer.

“I jumped at the chance,” Parker said. “The bug bit me. I’ve loved every moment I spend down there.”

She said 90 percent of the people who visit the museum do so to do research. They want to know where their relatives lived or who owned their old houses before they purchased them. They are particularly interested in the pictures the museum keeps of the old houses.

Parker and O’Brien have been doing research long enough to know who the original owners were of most of the houses in town. The museum has a large, 1859 Waldo County map that shows who owned which Lincolnville properties back then. Names still common in town today, such as Knight, Andrews, Richards, Levenseller and Calderwood, dot the hand-drawn map, which also shows the location of sawmills, schoolhouses, grist mills and lime kilns. And the museum keeps old census records to help people trace the history of their houses or properties.

Parker and O’Brien have spent many hours in recent years transcribing town records and letters and diaries, such as the one kept by Ralph Richards, a 29-year-old Spanish American War veteran and rural mail carrier. He wrote in it every day for 58 years, from 1908 until he died in 1966.

O’Brien said they welcome local residents and others with Lincolnville ties to share their family stories. They will even copy photographs free of charge and write up family histories.

The historical society plans to have a collection of books and a display at the new Lincolnville Community Library once it opens in the old Center Schoolhouse that is currently being renovated. The library site will also have an open-air museum to house antique farm implements. The main Schoolhouse Museum, however, will remain in its current home at 33 Beach Road (Route 173).

The museum is open Monday, Wednesday and Friday, 1 to 4 p.m., from June to October. Admission is free. For more information, e-mail abchparker@yahoo.com or visit the website at lincolnvillehistory.org.

Sheila Polson is an editor and journalist in Lincolnville. She is also chairman of the Lincolnville Community Library Committee.

Event Date

Address

United States