Setting up for the 'grand middle' in Camden Harbor, and lighting the sky

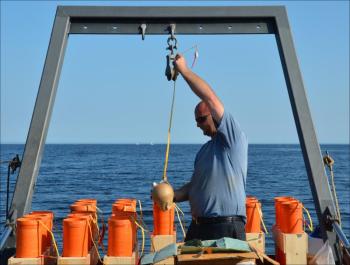

Jeremy and Shannon Hay, husband and wife, set up fireworks on a barge in Camden Harbor, near Curtis Island, for the July 4, 2013 birthday celebration of the United States. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jeremy and Shannon Hay, husband and wife, set up fireworks on a barge in Camden Harbor, near Curtis Island, for the July 4, 2013 birthday celebration of the United States. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The barge is set up between Curtis Island and Dillingham Point. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The barge is set up between Curtis Island and Dillingham Point. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

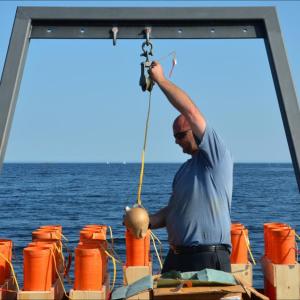

Jeremy Hay loads

Jeremy Hay loads

Camden's Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo, Fire Chief Chris Farley, Greg Sarno, and Jeremy and Shannon Hay move the merchandise to the Welcome, Camden's gunboat.

Camden's Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo, Fire Chief Chris Farley, Greg Sarno, and Jeremy and Shannon Hay move the merchandise to the Welcome, Camden's gunboat.

Camden Fire Chief Chris Farley and Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo load up the fireworks on the gunboat. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Camden Fire Chief Chris Farley and Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo load up the fireworks on the gunboat. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The Welcome, loaded with fireworks, heads out into Camden Harbor. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The Welcome, loaded with fireworks, heads out into Camden Harbor. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Fireworks on the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Fireworks on the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A truck full of fireworks. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A truck full of fireworks. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By dusk, people were rowing and paddling into the harbor, settling within a 450-foot perimeter from the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By dusk, people were rowing and paddling into the harbor, settling within a 450-foot perimeter from the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ashleigh and Eric Verite take advantage of a hot July 4 in Camden to paddle. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ashleigh and Eric Verite take advantage of a hot July 4 in Camden to paddle. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By 5 p.m. July 4, Camden Harbor was busy. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By 5 p.m. July 4, Camden Harbor was busy. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Or, there were shores to explore. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Or, there were shores to explore. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Carolyn Albertson, Aaron Annis and Michael Streat were among the unsung heroes, the clean-up crew on the harbor to rake the waters of any fireworks debris.

Carolyn Albertson, Aaron Annis and Michael Streat were among the unsung heroes, the clean-up crew on the harbor to rake the waters of any fireworks debris.

Jeremy and Shannon Hay, husband and wife, set up fireworks on a barge in Camden Harbor, near Curtis Island, for the July 4, 2013 birthday celebration of the United States. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jeremy and Shannon Hay, husband and wife, set up fireworks on a barge in Camden Harbor, near Curtis Island, for the July 4, 2013 birthday celebration of the United States. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The barge is set up between Curtis Island and Dillingham Point. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The barge is set up between Curtis Island and Dillingham Point. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Jeremy Hay loads

Jeremy Hay loads

Camden's Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo, Fire Chief Chris Farley, Greg Sarno, and Jeremy and Shannon Hay move the merchandise to the Welcome, Camden's gunboat.

Camden's Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo, Fire Chief Chris Farley, Greg Sarno, and Jeremy and Shannon Hay move the merchandise to the Welcome, Camden's gunboat.

Camden Fire Chief Chris Farley and Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo load up the fireworks on the gunboat. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Camden Fire Chief Chris Farley and Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo load up the fireworks on the gunboat. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The Welcome, loaded with fireworks, heads out into Camden Harbor. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

The Welcome, loaded with fireworks, heads out into Camden Harbor. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Fireworks on the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Fireworks on the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A truck full of fireworks. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

A truck full of fireworks. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By dusk, people were rowing and paddling into the harbor, settling within a 450-foot perimeter from the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By dusk, people were rowing and paddling into the harbor, settling within a 450-foot perimeter from the barge. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ashleigh and Eric Verite take advantage of a hot July 4 in Camden to paddle. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Ashleigh and Eric Verite take advantage of a hot July 4 in Camden to paddle. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By 5 p.m. July 4, Camden Harbor was busy. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

By 5 p.m. July 4, Camden Harbor was busy. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Or, there were shores to explore. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Or, there were shores to explore. (Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

(Photo by Lynda Clancy)

Carolyn Albertson, Aaron Annis and Michael Streat were among the unsung heroes, the clean-up crew on the harbor to rake the waters of any fireworks debris.

Carolyn Albertson, Aaron Annis and Michael Streat were among the unsung heroes, the clean-up crew on the harbor to rake the waters of any fireworks debris.

CAMDEN — At any point in Maine where fireworks are exploding on July 4, there's a strong chance that its crews from Central Maine Pyrotechnics that are lighting the fuses, blasting horsetails, spiders, golden waves, willlows and dahlias overhead, or shooting water cakes into the water which then erupt into the sky. Before the shows that draw thousands out of the woodwork, there are long and careful preparations. For the three who produced the fireworks in Camden, their day began at 6 a.m., when Jeremy Hay shook his wife, Shannon, awake. "We gotta go," he told her. "And, no, there's no time for coffee."

The Hays, who are but two members of this longtime family business, gathered up a friend, Greg Sarno, and headed from their homes in Old Orchard Beach to the "magazine" in Hallowell. There, they packed a truck full of racks containing tubes that would eventually be packed with four-inch, five-inch, six-inch shells. They drove toward the coast, arriving in Camden at 2 p.m., at Steamboat Landing. Maneuvering the truck in between Subarus and Toyotas that were unloading kayaks and stand-up paddleboards, Hay backed his rear tires into the water and against the cement wharf.

Meanwhile, Camden's Chief Deputy Harbor Master Jim Leo motored the town's utilitarian gunboat, the Welcome, to the landing, where he, the three from Pyrotechnics, and Camden Fire Chief Chris Farley started an assembly line, loading boxes, pallets and racks into the boat. The fireworks are sent directly from China to Hallowell, a relationship cultivated by the Central Maine Pyrotechnics. Hay's uncle, owner of the business, travels to China, visiting the factory. The family-owned business appreciates the handiwork of the product, said Hay.

"This is gorgeous tonight," said Jeremy. "This wins. Hands down."

Hay joined the family business after leaving the military in 1997 at age 23. He has been doing shows ever since. On July 4, 2013, he was in Camden, while his father, Earl, was on the sand at high tide at Old Orchard Beach, igniting $15,000 worth of fireworks in that tourist town. In Camden, the fireworks were funded by donations, an effort coordinated by the Penobscot Bay Regional Chamber of Commerce. The chamber calls it the Great Fourt of the July Camden Firework Celebration, and noted lead donors this year as Anonymous, Thomas Payne, Smiling Cow, Downeast Enterprise, Abigail's Inn, Cappy's Chowder House, Camden Accommodations and the Schooner Mary Day.

The fireworks crew estimated the evening represented $7,500 worth of explosives.

Hay, his wife Shannon and friend Greg, were going to be on Islesboro July 5, with another show, and then again the next night on Vinalhaven. On July 4, Central Maine Pyrotechnics crews were also in Winthrop, Freeport, Augusta, Thomaston and elsewhere. The company has enough licensed operators to stage 39 individual shows in a given night, said Jeremy's father, Earl.

Shannon, who accompanies her husband to the shows, assists in the setting up, then she steps way back.

"When he's doing a show, I make sure he's OK, and then I stay way the hell away," she said.

By later afternoon, the three had settled in on the barge provided by Adam and Brad Scott, owners of Two Harbor Marine. They had brought along sandwiches for supper and were busy arranging tubes along the deck.

Staging a fireworks show requires precise protocol: Operators put on protective gear, safety glasses, hard hats, boots, ear plugs and life jackets. The chief operator decides how he wants to paint the sky, and there is constant conversation about how the public — the people on the ground — are going to see the display.

Hay scopes out the wind direction, the waves, and the conditions of the sky. On July 4 in Camden, high clouds lifted over the mountains, and there was a slight haze of heat; otherwise, it was a perfect summer night. Crowds had gathered in Harbor Park, along the shores, and in restaurants lining the water. They were on rooftops in downtown Camden, or they were in boats, sitting on the tops of deckhouses, or down in rowboats and canoes and kayaks. The downtown was full and business doors were wide open. Summer had arrived and music, which had been playing all afternoon at Harbor Park, courtesy of many different bands, was still filling the air.

On the barge, Jeremy, Shannon and Greg were still packing tubes and threading fuses. Jeremy would light each fuse himself.

"You want it to look good," he said. "I have a set rhythm what I shoot to. The crowd loves the noise."

They even gauged the exact timing of the first lighting. Would 9 p.m. be right, or should they wait a few minutes longer so the people stuck in traffic and trying to get into town not miss any minutes of the show? They tentatively agreed 9:07 might be a good compromise.

"Jeremy's not doing an electronic display," said Shannon. "He's firm that he does it himself. He's fearless."

Mary Ann MacMaster, an inspector of the Office of the Maine State Fire Marshal, had visited Steamboat Landing that afternoon, ensuring all was in order from her perspective, and warning doubly that should any humans venture onto the shore at nearby Curtis Island to watch the fireworks, the show would be stopped. The perimeter was set at 450 feet, and harbor masters, assistant harbor masters, Maine Marine Patrol and the Coast Guard were all out in the harbor by dusk holding the line.

The power of fireworks lies in the discovery of black gun powder more than 2,000 years ago in China, and their art form has been refined over centuries by the Italians, Germans and British.

"At some point between 600 and 900 A.D., Chinese alchemists — perhaps hoping to discover an elixir for immortality — mixed together saltpeter (potassium nitrate, then a common kitchen seasoning), charcoal, sulfur and other ingredients, unwittingly yielding an early form of gunpowder," says the History Channel. "The Chinese began stuffing the volatile substance into bamboo shoots that were then thrown into the fire to produce a loud blast. The first fireworks were born."

Camden's fireworks on July 4 lasted a little approximately 17 minutes, and to the surprise of many, there was no grand finale with this show. The display, however, had been well-timed, and a series of impressive cascades had appeared early on in the show. Some muttered, others shrugged their shoulders and exclaimed over the 'grand middle,' questioning, 'do we always need a grand finale?'

A grand finale means a shorter show, so what would people rather have, a longer show or a shorter display with a packed finale? That's the question for the public, said Leo.

But Jeremy Hays said July 5 that it the lack of a grand finale was unintentional.

"I had a rack blow up on me in the show," he said, in a phone call from Islesboro." Did you see me running really quick? I feel horrible about it. I have a very specific way of doing a grand finale. I didn't get to put my signature on the show."

He said he would try it again at the Windjammer Festival, which takes place at the end of the summer in Camden.

"I promise to redeem myself," he said.

In the end, the skies darkened, and as the celebratory boat and car horns settled down, everyone made their way home, or to the bars. On the harbor, however, clean-up crews organized by Leo raked the waters of debris while the Pyrotechnics crew unloaded from the barge. Clean-up crew this year consisted of Aaron Annis, Michael Streat and Carolyn Albertson. They all finished by midnight, and they, along with the firefighters stationed around town and chamber volunteers, are considered the unsung heroes of the July 4 celebration.

-----------------------------------------

Editorial Director Lynda Clancy can be reached at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com; 706-6657.

Event Date

Address

United States